Precision time is ubiquitous today thanks to GPS and WWVB. Even your Macbook or smartphone displays time which is synchronized to the NIST-F1 clock, a cesium fountain atomic clock (aka the ‘Atomic Clock’) that is part of a global consortium of atomic clocks known as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Without precise timing there would be train collisions, markets would tumble, schools would not start on time, and planes would fall out of the sky.

But how was precision timing achieved in the 19th century during the era of steam, brass, and solenoids? One of the first systems of precision timing kept trains running safely and on time, rang the bells at school, and kept markets trading by using a special clock designed by the Self Winding Clock Company. Through measurements of celestial objects by the US Naval Observatory, and time synchronization pulses broadcast by the Western Union telegraph network, this system synchronized time across the United States in an era where the speed of our train system was out-pacing by the precision of our clocks.

Those clocks were designed so well that many of them are still around and functioning. One of these 100-year-old self-winding clocks made its way onto my workbench. I did what any curious hacker would do, figured out how the synchronization worked and connected it to a clock source with atomic precision. Let’s take a look!

Clock Synchronization That Was Ahead of Its Time

The world changed at the 1893 Columbian Exposition; electricity came of age, tens of thousands of lightbulbs adorned buildings, AC won the battle of the currents, and a system of precisely synchronizing clocks across the entire United States was introduced by the Self Winding Clock Company.

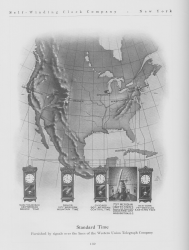

Day-to-day precise timing was provided by the US Naval Observatory in Washington DC who would measure the solar transit of either Mercury or Venus to synchronize the observatory master clock (there were three of them to check the others). This served as the master clock of the entire United States. This official time was transmitted to Western Union for re-transmission via the Western Union network to the regional and local offices.

A time synchronization pulse would be transmitted from the local Western Union office once per hour at the ‘top of the hour’ to customers who were subscribed to the synchronization service. Each customer would pay $1.25 per month per self-winding clock — some subscribers would only synchronize one clock but there were also entire buildings, offices, factories, schools, and train stations connected to the service.

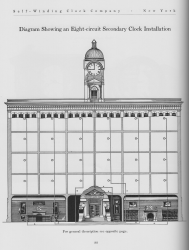

The block diagram below shows a master clock receiving synchronization signals from Western Union. With precise timing, the master clock controls a plurality of secondary clocks.

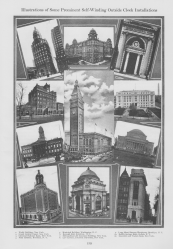

Secondary clocks were electronic repeaters that would simply repeat the time indicated on the master clock using electromagnetic solenoids, updating the time displayed on their clock faces every 30 seconds. Any number of secondary clocks could be used in large scale installations. This clock system and its precision timing service was very popular. Shown below are many prominent examples of Self-Winding-Clock installations as of 1908.

You’ve Probably Seen These Self-Winding Clocks

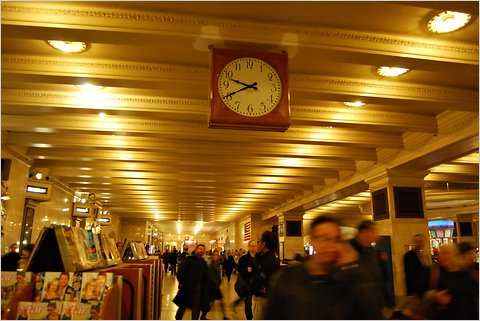

Although the Western Union time service ended in the 1960’s, Self Winding clocks are still in operation all over the country, including several at Grand Central in NYC:

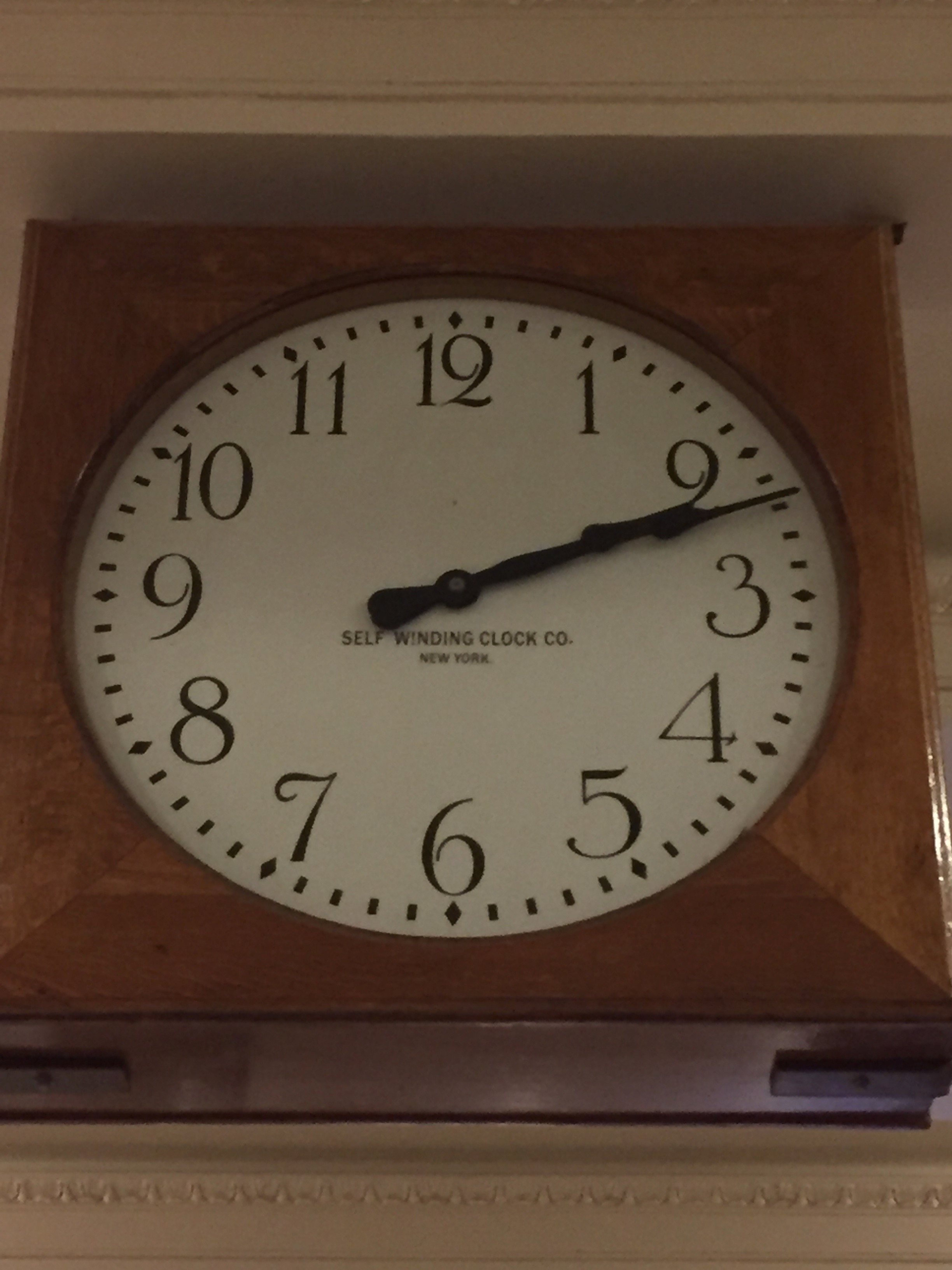

Similar in appearance to the oak cased clock at Grand Central, I was fortunate enough to be given a Self Winding Clock by a friend of mine Josh Levine. Another friend of mine, Larry McGlynn, helped me to date the movement to between 1910 and 1930 based on its serial number. So I consider this to be a 100 -year-old clock.

Usually I expect to spend some serious repair time when I acquire an old clock. This means disassembling, cleaning, oiling, and re-assembling the entire movement to get it working like new. I was lucky here because Josh had already serviced the movement and it was running strong. But after starting the movement it died within the hour. That was weird, usually pendulum wall clocks last for 8 days on a wind and I’d certainly expect it to go for more than an hour after such a strong start.

It turns out that this was a feature not a bug. I learned that the main spring barrel for this clock movement could only support 1 hour of output before the clock would stop. It self-winds using battery power and it deliberately only puts one hours worth of tension into the mainspring to maintain a consistent torque on the gear train for the purpose of maintaining accuracy and minimizing wear on the pivots. It runs for just one hour on a wind.

How Self-Winding Clocks Work

Here is how it works; the clock winds up and runs for about an hour. After an hour a cam closes a circuit and turns on the self-winding motor which winds the main spring until another cam shuts off the motor. The winding tension is good for about 1 hour then the entire process starts over again.

This is not a spinning motor with brushes and a stator. Instead, it is a pair of solenoids that pulls a lever arm with a paw gear which pushes a gear wheel. As soon as the lever arm is raised by the solenoids the electrical connection to the solenoids is broken, causing the lever arm to immediately fall back down again. This action repeats itself over and over again in a jack-hammer-like motion winding the main spring until the switch on the mainspring stops the motor. Chug chug chug!

Using a pair of 1.5V dry cells in series this clock will operate for at least 1 year before the batteries die. Interestingly enough, modern D-cells are functionally equivalent to the old dry cells, so expect 1 year of operation out of a pair of D cells.

The engineers of this clock movement could have used a DC motor with brushes but they choose this motor. I can only guess that a decision was made to use this motor architecture for long-term reliability. I can tell you that my motor still works reliably at 100 years old. By contrast, I’ve found that even mil-spec brushed DC motors from 75 years ago require a great deal of care to make them spin again.

Synchronization a 100-Year-Old Clock with GPS

For a while I was subscribed to Hackerboxes to force myself to learn how to use Ardunio and other easy-to-use embedded controllers. One of the projects was called ‘Clockwork’ and included a GPS module. I wrote a simple sketch feeding GPS time to the 7 segment display and put all of that together into a nice project box resulting in this Arduino-controlled GPS clock which covers two time zones and displays GMT.

This Arduino-GPS clock came in handy for controlling my 100-year-old Self Winding Clock synchronization solenoid. To synchronize the Self-Widing Clock I added a relay board and wrote a sketch to emulate the Western Union time protocol, thereby making the big clock synchronized to GPS. The protocol is simple, and well-described in this video by J. Alan Bloore. At the top of the hour a three-volt pulse is sent to the synchronization solenoid for less than one second. The synchronization solenoid then pulls the minute hand straight up to the 12 o’clock position.

I choose to use a 5V pulse to give it extra torque and decided to leave the pulse on for 500 mS. I put together a video overview of this entire project. If you’d like to jump to the demo of my clock synchronizing itself to GPS, start about fourteen minutes into the video.

After Nearly 1 Year of Operation

Every hour there’s a chugging noise that kind of sounds like a sewing machine, this is the self-winding action. At the top of every hour there is a loud and satisfying clunk-clunk which is the synchronization solenoid pulling the minute hand into position. If I leave my R390A comm receiver tuned to 10 MHz then the clunk-clunk happens at precisely the same time as the long beep transmitted from WWV at the top of the hour. All of this makes for an impressive horology demo for our house guests.

This clock was put back into continuous service just before new years 2018 and continues to give reliable and accurate service to this day without incident. Not only does it serve as the shop clock, I also use it to synchronize my various other clocks and watches that I tinker with.

I’d love to hear from those of you that have your own self-winding clocks in the comments below. And if you are interested in precision timing in general then I suggest joining the Time Nuts email list. From here you will receive numerous email discussions about precisely measuring time, oscillator frequencies, oscillator drift, phase noise, and many other topics.

No comments:

Post a Comment