Six years before Deepwater Horizon exploded in April 2010, the force of Hurricane Ivan blew an offshore drilling platform off its legs and into the Gulf of Mexico. For the last 14 years, that well’s pipes, long buried in mud and debris have been spilling oil into the Gulf every single day. That makes it the longest-running spill in history. Every day for fourteen years. Let that sink in for a bit.

Taylor Energy’s platform sat just 10 miles off the coast, much closer to the Louisiana shore than Deepwater Horizon was. Since the hurricane hit, Taylor has tried a number of unsuccessful things to stop the spill. They’ve only been able to plug 9 of the 25 broken pipes so far. The rest are buried deep in mud and debris. Why on Earth haven’t you heard about this before? Taylor spent six years covering it up. And they might have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for pesky watchdog groups surveying the Gulf after Deepwater Horizon exploded.

So how are oil spills stopped, anyway? The answer depends on many things. Most immediately, the answer depends whether the spill happened onshore or offshore, and the inciting incident that caused the spill. Underwater oil spills are much more difficult to stop because of the weight and existence of the ocean. In Taylor Energy’s case, the muddy Gulf bed has become a murky tomb for the broken and buried pipes, which makes it even more messy.

There’s More Than One Way to Spill Oil

Oil spills have many causes, and they run the gamut from pure accident to act of warfare. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground thanks to broken radar and an absent captain. Pipelines break, underground storage tanks leak. Once in a while, tankers simply collide in the ocean.

The largest spill to date was done purposely by Iraqi soldiers during the Gulf War in a failed attempt to keep US Marines from descending upon the beaches. BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig exploded due to many factors, including a surge of natural gas.

The Taylor Energy platform was capsized by hurricane-force winds. Seems like an act of God, right? Yes, but there’s a little more to it than that. For one thing, the walls of the platform were planted several hundred feet down into mud. If you think that sounds like a bad idea, you’re right. The same risk that made it unwise to build the platform there makes it unsafe and difficult to deal with the spill.

According to LSU law professor Ed Richards, the risk is well known. And yet, many rigs dot this area of coastal Louisiana. When Hurricane Ivan came raging into the Gulf, the force of the waves turned the rig’s foundation into an underwater mudslide.

How to Stop the Hemorrhaging

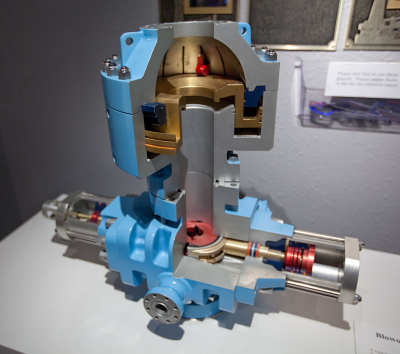

Oil and gas wells are equipped with blowout preventers as a first line of defense. These are made up of special types of valves that can kill the well by severing the pipe. The blowout preventer is what should have saved Deepwater Horizon. When it exploded, a couple of crew members tried to engage the blowout preventer, which had failed to do so automatically.

The BP engineers tried to use underwater robots to trigger the blowout preventer, but a crucial valve was stuck and it didn’t work. Then they tried to lower a four-story steel containment dome over the whole thing. The idea was to trap the billowing plumes of oil and then vacuum them up. But fumes from the oil caused crystallization, and this produced gases that kept the dome buoyant. They also tried drilling relief wells with the ultimate intent of injecting mud and cement into the leaking well to seal it off.

Deepwater Horizon was a hot topic, so engineers tried everything short of nuclear weapons. Yeah, that’s a thing. The Russians have done it successfully at least three times, though all of those spills were onshore incidents. Basically, you drill an adjacent well at an angle and drop a nuke in it. The shock wave shifts and melts the surrounding rock, flattening the pipe and sealing off the well.

The viability of any given spill-stopping method depends on the situation. Underwater oil spills like Taylor Energy and Deepwater Horizon are much more difficult to monitor and fix than onshore spills. If you want a deep but comfortable dive into the gargantuan, months-long effort to stop the Deepwater Horizon spill, then check out this excellent coverage from the New York Times.

The Junk Shot and Three Views to a Kill

Some of the techniques for stopping spills have colorful names. Most of them aren’t environmentally friendly, but when you’re dealing with oil billowing into the ocean at an alarming rate, you’ll try almost anything. Engineers tried all of these and more to stop the BP spill.

The junk shot involves shooting junk, namely golf balls, tennis balls, shredded tires, and old, knotted-up rope into the blowout preventer. The idea is to clog it temporarily, and then start shooting mud and cement to stop it permanently. It sounds like a strange mix of wastefulness and re-use, but it worked to stop the 1991 spill in Kuwait.

Somewhere between the four-story steel box idea and the junk shot operation, those dealing with Deepwater Horizon tried something called the top kill. This involves pumping heavy mud through the blowout preventer and into the well to overcome the pressure of the rising oil.

They later tried the static kill, which is pretty much just top kill at a slower mud rate. Since the mud is much heavier, it will force the oil back down into the reservoir. Then it’s time to start pumping cement to seal it off.

Finally we come to the bottom kill. This one should have a different name, because it’s far more elegant than the other kills. Although things got a bit dodgy, it was the bottom kill that finally stopped Deepwater Horizon. First, engineers lower a magnetometer down a relief well. This induces a current in the well’s steel casing and generates a magnetic field, which helps engineers pinpoint the exact location of the leaking well. Then they drill into the hull of the leaking well and pump mud and cement down through the relief well to plug the leak.

Dealing with a Teenage Oil Spill

No two spills are the same, not even Deepwater Horizon and Taylor Energy. Deepwater Horizon spilled a lot of oil very quickly, and the oil was highly visible on the surface. The Taylor spill amounts to less than a gallon per day on the surface, but an estimated 100 barrels per day below the surface.

In 2008, Taylor set up a $666 million dollar trust to deal with the spill, and were bought out soon after by a pair of Korean companies. Since then, Taylor Energy has existed only to monitor the incident response. Studies done by the Coast Guard determined that the remaining 16 pipes posed little environmental risk, so Taylor sued the government to get the balance of their money back. Naturally, the government did a new study, and they determined that Taylor had under-reported the leak. Based on oil reserve estimates, they believe the leak could go on for 100 more years if no one is able to stop it.

A few months ago, the Coast Guard decided they would try the containment dome solution on the Taylor spill. Taylor Energy, which has been bankrupted down to a single employee, believes this will make the problem worse, so they decided to sue the Coast Guard.

Whether the Taylor spill can be stopped or not, there’s still the matter of all the oil polluting the oceans. There is one hope, though, and that’s oil-eating bacteria. One way of dealing with spills is to release dispersants into the water. These break down the oil globules so they can be consumed by certain types of bacteria that feed on hydrocarbons. It may not be the slickest solution, but it’s a start.

No comments:

Post a Comment