Astronomy is undoubtedly one of the most exciting subjects in physics. Especially the search for exoplanets has been a thriving field in the last decades. While the first exoplanet was only discovered in 1992, there are now 4,144 confirmed exoplanets (as of 2nd April 2020). Naturally, we Sci-Fi lovers are most interested in the 55 potentially habitable exoplanets. Unfortunately, taking an image of an Earth 2.0 with enough detail to identify potential features of life is impossible with conventional telescopes.

The solar gravitational lens mission, which has recently been selected for phase III funding by the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program, is aiming to change that by taking advantage of the Sun’s gravitational lensing effect.

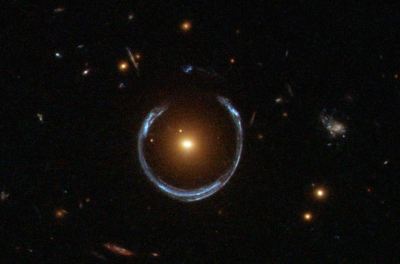

It all started with Einstein

Not surprisingly, it was Einstein who calculated in 1936 that the gravitational field of a star can act as a lens. If an object is located behind the star on the same line of sight as the observer, the resulting image will form a ring, nowadays known as an Einstein ring. It was not until 1979 that the effect was discovered when two suspiciously similar objects were observed turning out to be a double image formed by a gravitational lens. Today gravitational lensing is used to quantify the amount and distribution of dark matter. As hinted in the introduction, due to the brightness amplification caused by a gravitational lens it can also serve as a kind of gravitational telescope, allowing the detection of faint galaxies from the early Universe.

AI and Citizen Scientists help to find Needles in a Haystack

Gravitational lenses are quite rare and one typically has to look at a thousand different galaxy images to find one. In addition, recognizing and unwinding the distortion of a gravitational lens on an image is not a trivial task. Therefore, the space warps project relied on citizen scientists to identify gravitational lenses within data taken by the Hyper Suprime-Cam. (Astronomers pick epic-sounding names!) Machine learning algorithms can also be used to sift through the data of astronomical surveys. In particular, convolutional neural networks, which are also the basis for Facebook’s DeepFace facial recognition, have been used to identify gravitational lenses.

Using the Sun as a Lens

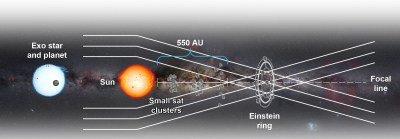

In contrast to an optical lens, a gravitational lens does not produce a single focal point but a focal line. As shown in the picture, the Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL) focusses incoming light to a line that starts at a distance of ~550 AU. If one would place a telescope at this point the SGL could magnify the brightness of a distant object by a factor of ~1011 and offers an angular resolution of ~10-10 arcsec. For an exo-Earth at 30 parsecs (~100 light-years) the SGL telescope could achieve ~25 km-scale surface resolution, enough to see surface features and signs of habitability.

A String-of-Pearls equipped with Solar Sails

The concept of the SGL mission is very well explained in the video embedded below. First of all, one of the biggest problems is getting to the Sun’s focus point. The most distant space probe Voyager 1 launched in 1977 is currently at 148 AU, i.e. at the same velocity, it would take >150 years to get to the nearest SGL focus point. Because of the required velocity and long operating life current chemical and nuclear propulsion techniques are inadequate. Instead, the SGL mission will use solar sails driven by the Sun’s radiation pressure. By flying closely around the Sun the SGL spacecraft could achieve a velocity of 25 AU/year, reaching the SGL focus region in <25 years total flight time.

Employing a single spacecraft would be impractical for the SGL mission because of the high risk of failure during the long flight. Instead, the mission concept follows a string-of-pearls approach where a pearl consists of 10 to 20 small spacecraft (smallsats) weighing <100 kg that fly in formation. The entire string will be formed by multiple pearls launched at ~1-year intervals. Having multiple smallsats allows for some redundancy thereby limiting the risk of single point failure. It also helps to spread the costs over time and among the participants. Otherwise, a mission of this magnitude will likely never be able to secure enough funding.

Each smallsat should operate mostly autonomously which becomes more important the further away it gets from Earth. The final SGL communication latency is around four days. To achieve autonomous navigation, data processing, and fault management the SGL mission counts on several emerging AI technologies and throws around a lot of buzzwords like Explainable AI, Lifelong Learning Machines, Learning with Less Labels, and Neuromorphic chip design.

Challenges also arise for the imaging instruments. A coronagraph, made of a phase mask that works through destructive interference, is being used to block out the direct light from our Sun. This still leaves the light from the Sun’s corona as background source, which will overlap with the Einstein ring. To reduce this overlap the telescope needs to be placed yet further away from the Sun at about 650 AU. Finally, the telescope will not be large enough to image the whole Einstein ring at once. The image of an Earth-sized exoplanet at 30 parsec is compressed by the SGL to a cylinder with a diameter of ~1.3 km in the immediate vicinity of the focal line. For a 1 m telescope to obtain a 1000 x 1000 pixel image, the spacecraft would have to scan this area one pixel at a time by moving in small steps of 1.3 m. The original image of the exoplanet is then reconstructed via a deconvolution algorithm.

When do we get there?

So when will we get the first high-resolution image of an exoplanet? Naturally, the timelines for science projects of this magnitude are very vague and can easily get shifted behind by 5-10 years. In the phase II summary report it is stated that the remaining technological development would allow launch in 2028-2030. Realistically, this means we could get first data somewhere around the early 2060s.

What planet will they look at? Since there will likely be several new potentially habitable planets discovered before the SGL mission will reach its destination, the target is not yet fixed. Currently, one the most promising candidates is TRAPPIST-1e, a rocky, almost Earth-sized planet located at 12.1 parsecs distance that may also contain liquid water. The planet will be more closely observed by the James Webb Space Telescope planned to launch next year.

What will they look for? Checking for signs of habitability will include spectroscopic investigation of the atmosphere to check for biomarkers such as oxygen and methane. It will also be possible to look for artificial light sources at night time as well as radio transmissions.

The Sun has not only enabled life on Earth but can also serve as a tool to search for life on other planets. It is quite exciting that the question “Are we alone in the Universe?” may be answered with a negative within our lifetime. This makes you wonder how many similar telescopes are already pointed at us.

No comments:

Post a Comment