Ventilators are key in the treating the most dire cases of coronavirus. The exponential growth of infections, and the number of patients in respiratory distress, has outpaced the number of available ventilators. In times of crisis, everyone looks for ways they can help, and one of the ways the hardware community has responded is in work toward a ventilator design that can be rapidly manufactured to meet the need.

The difficult truth is that the complexity of ventilator features needed to treat the sickest patients makes a bootstrapped design incredibly difficult, and I believe impossible to achieve in quantity on this timeline. Still, a well-engineered and clinically approved open source ventilator might deliver many benefits beyond the current crisis. Let’s take a look at some of the efforts we’ve been seeing recently and what it would take to pull together a complete design.

Bag-Based Ventilator Designs

We’ve seen a number of designs based on a bag valve mask (BVM), also known by the brand name Ambu bag. You’ve likely seen these medical scenes on television where a large flexible bladder is squeezed by a medical worker to push air into the lungs of an unconscious patient. Many recent DIY designs work by automating the squeezing of this bag. This does the work of a BVM, but I hesitate to call them a ventilator because they lack many critical features. I’ll address those below, but it’s also worth your time to watch this fifteen-minute video detailing the topic:

The use of a BVM is most often found in short-term situations where a patient with otherwise healthy lungs needs to be kept alive until they can be transported by a proper ventilator: think of a 20-minute ambulance ride. These are not designed to be used for long periods of time and we’ve seen anecdotal reports that COVID-19 patients are needing invasive ventilation much longer than expected, at more than a week and in some cases multiple weeks. And then they need to be weaned back off them.

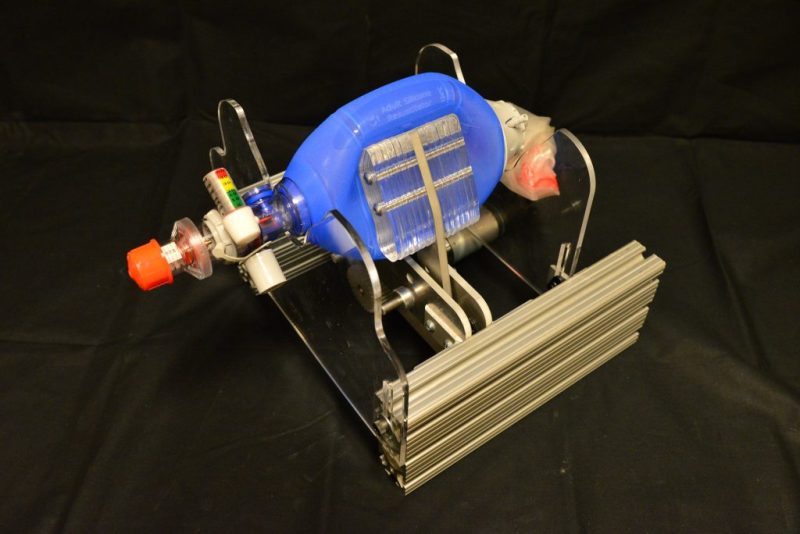

Seen here is the AmboVent design developed in Israel by a volunteer group that included both physicians and engineers. It’s one of the most advanced bag-based designs we’ve seen, yet it raises a couple of concerns. When providing invasive breathing support as shown by this intubated test patient, the air needs to be both heated and humidified — normally a function of the sinuses, which have been bypassed to insert a tube into the trachea. It’s unclear if designs like these can be used with an external humidifying device.

The design also lacks the granularity necessary for the sick lungs of COVID-19 patients. Both the inhale and exhale cycles need to to be carefully regulated and monitored to ensure that as much of the lungs are being used as possible and no damage is being done to the patient’s lungs. Although there is a pressure sensor and “breath profiles” in the software of this particular design, the only control is the rate at which the motor-controlled arm squeezes the bag. There is also no in-built mechanism for regulating the oxygen concentration being provided.

Other similar bag-based designs include the E-Vent from MIT which uses a band to squeeze the bag, and the OxVent coming out of the UK which places the bag in a chamber and uses compressed air to squeeze it. All of these designs operate on similar principles and have the same limitations. But by far the biggest limitations are the lack of sensors and the complexity of software. Patients using these machines are sedated and often partially paralyzed. Intensive care ventilators are able to sense air pressure, oxygen concentration, and breath rate and adapt quickly and accurately. Developing these features is software nightmare for a rushed product. And the lack of sensors to alarm under many possible failure states make these designs something that would require uninterrupted human oversight.

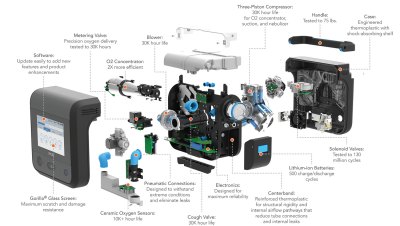

Tesla’s Ventilator Prototype is Closer But Still Far Away

The ventilator prototype demonstrated by Tesla engineers last week is certainly a step up from the state of the bag-based designs. That said, the clever bit of using an Ambu bag is that they’re already at every hospital in the world en masse.

The major advances found in Tesla’s design are the sensing mechanisms for both oxygen concentration and inhale/exhale pressures. As demonstrated in the video, there is a mixing chamber where oxygen is added to ambient air. The system can adjust based on oxygen concentration in the exhale tubing. There is also separate pressure sensing and actuation for both inhale and exhale cycles. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is one of the major challenges in treating COVID-19 patients and granular control of these separate pressures is a key component to treatment.

The sinuses are once again bypassed by this invasive ventilation, but since this design depends on a pump and not a compressed bladder with limited volume, it can likely be used with an external humidifying device. If this system were to be deemed usable it would still need to be manufactured, raising questions of supply chain availability, and the same “software nightmare” mentioned in the previous section will be present here.

Right Now We Have a Supply Chain Problem, Not a Design Problem

If you’re serious about ventilators, you simply must go and read Ventilators 101 by Bob Baddeley. This masterpiece of an article lays out the challenge of designing and manufacturing these advanced machines. These machines solve really hard problems of interfacing with the human body and I think it’s unlikely there are suitable shortcuts around their complexity. The good news is that we’ve already designed, tested, and extensively used them. But we’re having trouble making a lot of them right now.

So our problem right now isn’t ventilator design, it’s manufacturing supply chain. This is being worked on feverishly and by a huge number of people. This episode of the Planet Money podcast follows the sourcing of ventilator pistons. The ventilator manufacturer Ventec is partnering with General Motors who are spinning up their supply chain up to make tens of thousands of ventilators, with the first units planned to be in the field some time this month.

We have a desperate shortage right now and it is really awful. The hope is that the windfall of this supply chain effort will mean an abundance of this equipment. It’s worth mentioning that our most precious resource is not the equipment but the health care workers to operate it. Doing everything we can to support them and reduce the number of people who need care right now is, in my mind, an equally important problem to address. Thank you to these heroes who put their health at risk to heal others.

Long-Term, Does an Open Source Ventilator Design Make Sense?

What if there had been an Open Source ventilator design available in when this all began? Would it have made the difference when China was first seeing severe cases? Would it have made the difference in Italy, Spain, Europe, and the United States? Once again, the problem we’re having right now is in supply chain. It’s hard to say that we would have been able to build to the exponential need even if an open design were ready from the start, because similar supply chain issues would have presented themselves.

However, I do think that the “software nightmare” associated with new designs is something for which open source is extremely well suited. A highly scrutinized, well maintained, open source software stack would be a powerful asset when looking for solutions to a shortage such as this one.

The hardware side of things is a bit more difficult to envision as an open source project, simply because contributors to the project would need to be able to replicate the hardware — a problem faced by all open hardware projects. It’s not impossible, but maintaining a bill of materials that is widely available is extremely challenging. However, with mechanical drawings, CAD files, thorough specifications, and a superb testing regime, the task in a time of crisis becomes engineering around the specific gaps in your supply chain, rather than perfectly replicating the design.

Maintaining a design is also crucial. Will equipment manufactured today be possible to manufacture ten years from now without major redesign? Will the features still be relevant for our needs in ten years? Open source is powerful, but abandon-ware is less so. The open source community has many success stories about projects living long lives as maintainers pass the torch from one to the next.

Simply put, open source is people, if the community remains, so does the project.

Need for Ventilators Beyond COVID-19

One of the major problems we face is that ventilators are a low-volume medical product. There are a whole lot more washing machines out there than ventilators, and washers are cheap. There’s much more frequent need for washing machines, and if they don’t work right the consequence is merely a load of clothes that didn’t get clean. When you produce a lifesaving device to meet rigorous regulatory standards in small volumes the price ends up being very high. Open source projects are not free as in beer — it takes time and resources to build prototypes and have them certified. But once established the designs can be used without payment. If a design can meet the safety standards, the potential for widespread manufacture is an uplifting concept.

I’m saddened to learn that Nigeria has something like 500 ventilators for all of its 200,000,000 in population. Compare that to the United States with about 160,000 for a population of 330,000,000. In a time of crisis like this, we need a well reasoned system of sharing equipment and personnel across borders and oceans. I’ve seen some indication that this is happening with both Oregon and California loaning ventilators to New York, hopefully bridging the gap until those new ventilator supply chains mentioned earlier pay off. I hope this type of sharing will accelerate and be extended to all areas in need.

Once the crisis has passed, life-saving tools published as open designs could be one path toward greater availability. Nigeria’s number of ventilators sounds very low to me considering its population. Could countries in this situation take on their own manufacturing programs to grow their supply using dependable, tested, open source designs? That is a future I’d like see.

No comments:

Post a Comment