As the world pulls back from the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, it enters what will be perhaps a more challenging time: managing the long-term presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the disease. In the roughly two-century history of modern vaccination practices, we’ve gotten pretty good at finding ways to protect ourselves from infectious diseases, and there’s little doubt that we’ll do the same for SARS-CoV-2. But developing a vaccine against any virus or bacterium takes time, and in a pandemic situation, time is exactly what’s at a premium.

In an effort to create an effective vaccine against this latest viral threat, scientists and physicians around the world have been taking a different approach to inoculation. Rather than stimulating the immune system in the usual way with a weakened sample of the virus, they’re trying to use the genetic material of the virus to stimulate an immune response. These RNA vaccines are a novel approach to a novel infection, and understanding how they work will be key to deciding whether they’ll be the right way to attack this pandemic.

Stimulating by Simulating

The immune system is remarkably complex, consisting of a collection of cells and tissues that are capable of recognizing and eliminating invading organisms and developing an “institutional memory” of the conflict so that future infections can be dealt with rapidly. It can be a little hard to wrap your head around the terminology of the immune system, and so if it’s been a while since high school biology, you might want to check out the previous article I did on immune system testing for COVID-19, which covers the basics of the immune system.

At its heart, the immune system functions by responding to the proteins present in invading microbes, and it does so in a two-pronged attack. Things start with the innate immune system, a “rapid-reaction force” of cells that bind to and engulf any cell bearing non-self protein markers that manages to get inside the body. These invaders are broken down and the remaining proteins are presented to cells of the adaptive immune system, which then begins the slower process of creating antibodies that bind to the invader’s proteins with great specificity. These antibodies are greatly amplified to deal with the current infection, and when the threat is over, cells bearing these antibodies will remain at low levels, ready to mount another attack should the invader make a return visit.

Vaccination is a jump-start on the adaptive immune system’s attack. By challenging someone with either a killed sample of a pathogen, or a live version of it that has been weakened enough to not cause disease, the immune system learns what the disease looks like. By simulating an infection, vaccination primes the adaptive immune system, bestowing a degree of immunity without actually having to go through the disease process. There are, of course, caveats. Not every vaccination results in lifetime immunity; this is especially true with seasonal influenza viruses, which tend to mutate frequently and present different signatures to the immune system, requiring a new vaccine every year. But for the most part, priming the immune system through vaccination works well enough that dozens of once-deadly diseases are no longer a threat, and several have been eradicated.

Traditional vaccine production is a painfully slow process, though. Creating a version of the pathogen that correctly stimulates the immune system without causing the disease it’s meant to prevent is a tricky business. For viral vaccines, the first step is isolating the virus and growing large quantities of it. For influenza viruses, this is done using chicken eggs, to the tune of millions a year. Other viruses are grown in mammalian cell cultures, which tend to be very fussy about growing conditions. Once enough virus has been grown, it needs to be isolated from the growth medium, purified, and added to other ingredients that will make the vaccine suitable for injection. And that’s simply the manufacturing process; add in research and development and the time needed to conduct safety and efficacy trials, and time to market for a new vaccine can easily be measured in years.

The Vaccine Factory Inside You

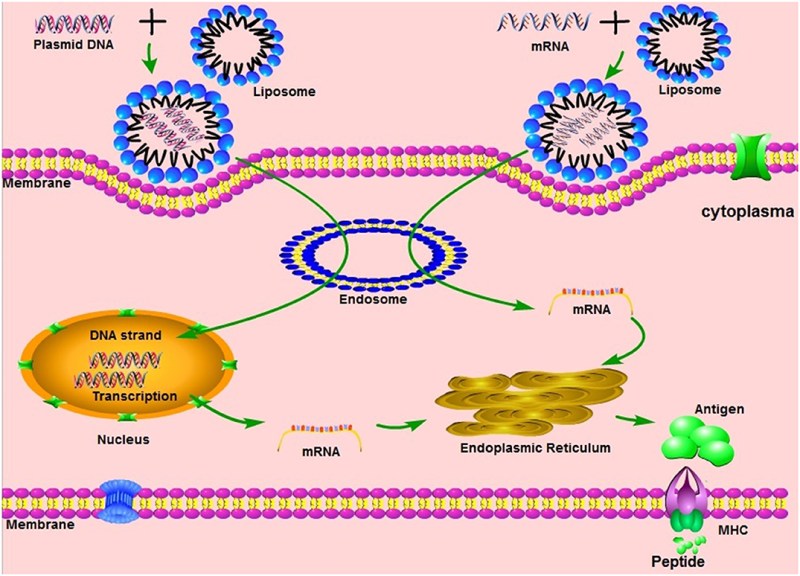

To shorten the development time of a new vaccine, manufacturers are attempting to leverage genetic engineering by essentially making the patient the manufacturing facility. RNA vaccines work not by introducing viral proteins into the patient but rather the instructions for making those proteins in the patient’s own cells.

Recall that messenger RNA, or mRNA, is produced in cells by the process of transcription, where sections of DNA inside the nucleus of a cell are copied into the single-stranded nucleic acid RNA. This transcript moves out of the nucleus of the cell to be used by ribosomes to create strings of amino acids in a process known as translation. These polypeptide strings then fold up into complex shapes that dictate their function as finished proteins. For a bit more detail on the process, check out my article on protein folding.

An RNA vaccine, then, seeks to place a specific RNA sequence into cells in such a way that it will be translated into proteins by them. It’s not at all unlike the actual process of viral infection, which results in the genetic payload of the virus hijacking the cell’s machinery to make more copies of itself. But where a virus injects a complete genome into the host cell, an RNA vaccine’s payload is very limited, and has no potential to destroy the cells it infects, which is what causes the symptoms associated with a viral infection.

Once an RNA vaccine has been introduced into a patient, things progress much as they would for a viral infection. The cells that take up the RNA will dutifully translate the genetic code it contains, producing the protein that the sequence codes for. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, most researchers seem to be concentrating on the viral spike proteins that stud the exterior of the virus and allow it to bind to receptors in the human respiratory and digestive tract. By producing large quantities of this protein, the patient’s own cells are doing the job normally done in chicken eggs or cell culture, with no need for expensive and time-consuming purification of the final product. And once the target protein, or immunogen, is created by the cells, it is readily available to train the adaptive immune system, which hopefully produces extended immunity.

Pros and Cons

The RNA vaccine process sounds reasonably straightforward, but as with all things involving biology, there’s more to the story. While some “naked RNA” vaccines have been tried, simply injecting a solution containing fragments of RNA won’t necessarily work. Anyone who has ever worked in a bio lab will tell you that RNA is notoriously delicate stuff. Unlike its double-stranded and relatively robust cousin DNA, RNA’s single strand leaves it open to attack by ribonucleases (RNases), enzymes that non-specifically cleave RNA into fragments. In the body, RNases play a crucial role in regulating protein production by limiting the lifetime of mRNAs, and chances are good that some or all of a vaccine consisting of just naked RNA would be degraded before producing any useful amounts of viral protein.

To work around the delivery problem, some companies are focusing on delivering RNA vaccines via lipid nanoparticles. This is exactly what it sounds like — an RNA sequence packed into a greasy little ball of fat. The idea is for the lipid container to protect the RNA from degradation and to make uptake by the patient’s cells easier, delivering the genetic payload exactly to where it can be used. Some manufacturers are even working on customized lipid packages that can target specific cell types within the body.

No matter what the delivery vector for RNA vaccines looks like, the bottom line is that we’re essentially building artificial virus parts — genetic payloads that hijack the cellular mechanism. The intention is therapeutic, of course, but the fact remains that by leveraging what our cells already do well, we might be able to get vaccines for COVID-19 and other diseases, perhaps even cancer, to a waiting world much faster than by trying to do it the traditional way.

No comments:

Post a Comment