When we draw schematics, we have the luxury of pretending that wire is free. There are only a few cases where you have to account for the electrical characteristics of wire: when the wire is very long or the frequency on the wire is relatively high.

This became apparent after the first transatlantic cable went into service for telegraph communications. Even though the wire was linear, there was still distortion on the line so severe that dots and dashes would overlap each other. The temporary solution was to limit speeds so slow that operators had trouble sending and receiving at those speeds. How slow? An average character took two minutes to send! That’s not a typo. Two minutes per character. By custom, Morse code assumes a word is five characters, so you could send a word every 10 minutes.

The first transatlantic cable went into service in 1858 and was virtually the moon landing of its day. Frustrated with how slow the communications were, an electrician by the name of Whitehouse decided to crank up the voltage to over 1,000 volts which caused the cable to fail after only three weeks in service. Whoops. Later analysis showed the cable was probably going to fail quickly anyway, but Whitehouse took the public blame.

The wire back then wasn’t as good as what we have today, which led to some of the problems. The insulation was made from multiple coats of a natural latex, gutta percha, which is what dentists use to fill root canals. The jackets were made from tarred hemp and bound with iron wire. There was no way to build an underwater amplifier in 1858, so the cables were just tremendous wires laying on the ocean floor between Newfoundland and Ireland.

State-of-the-Art

While putting a cable under the ocean today isn’t a minor undertaking, it was even worse in 1858. Even the construction of the wire was a big deal. There were seven conductors and the iron wire used to armor the cable required two companies to make it. Famously, the companies wound the wire around in opposite directions leading to a well-publicized hack to allow splicing.

Laying the cable was also precarious. There had been some work laying shorter cables under small bodies of water, but nothing of this scale had been done before. There wasn’t a ship that could hold all 2,500 miles of cable, so they used two ships. After a few aborted attempts, the ships met in the middle of the Atlantic, spliced their cables and set off in opposite directions. The finished cable itself was nearly 2,000 miles long.

Even Morse code didn’t work the same on the long cable. Instead of on or off, the transatlantic cable used current flow in one direction to signify a dot and in the other to signify a dash — what we would now call a current loop. The receiver end was a very sensitive galvanometer that used a mirror to maximize sensitivity, developed by a man named Thomson who is better known as Lord Kelvin. Thomson and Whitehouse didn’t get along very well, but Thomson’s ideas and predictions turned out to be the right ones.

Degradation

At first, it was a mystery how the cable could distort the signal. Tests with underground lines by Whitehouse had been successful, although Thomson disagreed with those tests and feared the cable would only support slow speeds. The cables were long, but the speed of light is very fast. Even if the cable’s velocity factor had been 0.25, the transmission delay would only be about 44 milliseconds. Not enough to worry about. Plus, if it simply acted as a delay that wouldn’t change the communication speed, just the latency.

Thomson based his idea that there would be speed issues on the law of squares. This law says that a voltage step into a cable will have maximum current at a time proportional to the square of the distance down the line. It turns out this is not exactly correct because the formula didn’t take into account inductance and leakage, but it was close enough to show that there could be problems with the delay in the line. The cable project was well underway, but the new formula indicated that the cable should be larger to reduce resistance and decrease capacitance. But, as so often happens, no one wanted to hear that so it was disputed and ignored.

The Real Reason

It would take Oliver Heaviside to get a better explanation of what was happening. Intuitively, you can consider that higher frequency components of a signal travel through the wire at different speeds than lower frequencies. A square wave, for example, can be thought of as a sine wave at the fundamental frequency plus the sum of all the odd harmonics. The higher harmonics travel faster than the lower frequencies, causing distortion. At some point, the higher frequencies of one part of the signal will catch up to the slower parts of the previous portion of the signal.

It would take Oliver Heaviside to get a better explanation of what was happening. Intuitively, you can consider that higher frequency components of a signal travel through the wire at different speeds than lower frequencies. A square wave, for example, can be thought of as a sine wave at the fundamental frequency plus the sum of all the odd harmonics. The higher harmonics travel faster than the lower frequencies, causing distortion. At some point, the higher frequencies of one part of the signal will catch up to the slower parts of the previous portion of the signal.

Heaviside formulated a pair of differential equations known as the telegrapher’s equations. In 1876 his paper provided a realistic model of a long transmission line and the work has applications in all sorts of transmission lines and even antennas. It turns out that Thomson’s law of squares was a special case of the telegrapher’s equations that ignored inductance and leakage.

The Solution

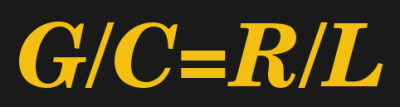

If you work through Heaviside’s math, you find out that distortion does not occur in a cable when for a given amount of cable, the ratio of leakage to capacitance is equal to the ratio of resistance to inductance. Mathematically if C is the capacitance per meter, L is the inductance per meter, R is the cable resistance per meter, and G is the shunt conductance (that is, the inverse of the resistance between conductors), you wind up with this formula, known as the Heaviside condition:

Usually, G is very small so G/C will be much less than R/L. So how can you balance the formula? Simply change one of the variables until the ratio works out. Decreasing R is attractive since lower R means less loss, too, but it also means bigger wire or more expensive materials, which is not always practical. Especially when you’re talking about a 2,000-mile cable. Decreasing capacitance has a similar problem. It does change the ratio, but requires more spacing or different insulation. You could increase G, but that will contribute to higher loss, so that’s not something you’d usually want to do.

That leaves the inductance, L. Some long cables have a built-in loading wire with high magnetic permeability to force the inductance higher. There is another way to deal with this and that’s through the use of discrete loading coils regularly spaced along the cable. This isn’t perfect, but it is practical and reduces distortion. These are sometimes called Pupin coils after inventor Michael Pupin. Pupin sued AT&T over a patent from George Campbell who used loading coils on telephone lines. Cambell’s patent was filed after Pupin’s, but the work appears to have been earlier. Heaviside’s work was even earlier, so Pupin probably didn’t have a good claim.

However, the value to AT&T was so large, they settled on buying an option for Pupin’s patent so they could control both patents. Pupin would up with about $455,000 over about 20 years — roughly worth $25 million today. But that was small change compared to AT&T’s savings. Lower distortion on phone lines meant they could use a cable to cover twice the distance they used before. There are estimates that AT&T saved $100 million in the first quarter of the 20 century. That makes the less than $500,000 Pupin got just a drop in the bucket.

How Times Have Changed

It’s hard for the modern mind to even imagine setting up a remote system when your only means of communication with the other side is a letter carried by ship. Bad weather could mean a transatlantic crossing would take weeks. The amount of money spent on the many cable attempts was also staggering. The successful cable took about $1 million. A huge sum in those days. After the first cable failed, some people claimed the whole thing was a hoax; truly the moon landing of its day.

Now, of course, wire is better and we don’t have to worry as much about the Heaviside Condition. In addition, you wouldn’t lay a 2,000 mile cable without repeaters. This not only combats loss but takes care of the distortion to some degree. But make no mistake. There are still plenty of undersea cables and they carry a huge amount of data.

While the history of technology like this is enjoyable in its own right, you have to consider what lessons you can draw from this story. First, wire is not perfect and behaves in unexpected strange ways that rarely make a difference (until they do). Second, ignoring technical advice for business reasons is often fraught with peril. It would be interesting to do a study on how much money was wasted because no one liked Thomson’s results that the cable would be “slow.” Granted, if the cable had failed anyway, it wouldn’t have been a huge loss, but still, having a cable with less distortion might have prevented the cable from failing as early as it did.

Pupin coils are largely a thing of the past. But the story of how they came and went can teach us things today. If you want to know more about the history of the transatlantic cables in more detail and how they evolved, we talked about that before. You might also enjoy the video below.

No comments:

Post a Comment