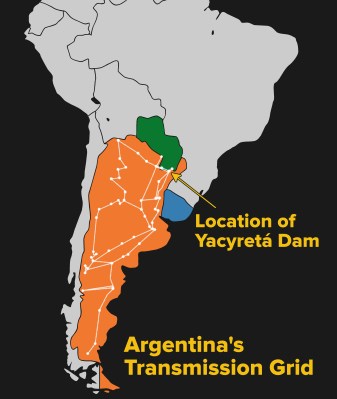

A massive power outage in South America last month left most of Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay in the dark and may also have impacted small portions of Chile and Brazil. It’s estimated that 48 million people were affected and as of this writing there has still been no official explanation of how a blackout of this magnitude occurred.

While blackouts of some form or another are virtually guaranteed on any power grid, whether it’s from weather events, accidental damage to power lines and equipment, lightning, or equipment malfunctioning, every grid will eventually see small outages from time to time. The scope of this one, however, was much larger than it should have been, but isn’t completely out of the realm of possibility for systems that are this complex.

Initial reports on June 17th cite vague, nondescript possible causes but seem to focus on transmission lines connecting population centers with the hydroelectric power plant at Yacyretá Dam on the border of Argentina and Paraguay, as well as some ongoing issues with the power grid itself. Problems with the transmission line system caused this power generation facility to become separated from the rest of the grid, which seems to have cascaded to a massive power failure. One positive note was that the power was restored in less than a day, suggesting at least that the cause of the blackout was not physical damage to the grid. (Presumably major physical damage would take longer to repair.) Officials also downplayed the possibility of cyber attack, which is in line with the short length of time that the blackout lasted as well, although not completely out of the realm of possibility.

Initial reports on June 17th cite vague, nondescript possible causes but seem to focus on transmission lines connecting population centers with the hydroelectric power plant at Yacyretá Dam on the border of Argentina and Paraguay, as well as some ongoing issues with the power grid itself. Problems with the transmission line system caused this power generation facility to become separated from the rest of the grid, which seems to have cascaded to a massive power failure. One positive note was that the power was restored in less than a day, suggesting at least that the cause of the blackout was not physical damage to the grid. (Presumably major physical damage would take longer to repair.) Officials also downplayed the possibility of cyber attack, which is in line with the short length of time that the blackout lasted as well, although not completely out of the realm of possibility.

This incident is exceptionally interesting from a technical point-of-view as well. Once we rule out physical damage and cyber attack, what remains is a complete failure of the grid’s largely automatic protective system. This automation can be a force for good, where grid outages can be restored quickly in most cases, but it can also be a weakness when the automation is poorly understood, implemented, or maintained. A closer look at some protective devices and strategies is warranted, and will give us greater insight into this problem and grid issues in general. Join me after the break for a look at some of the grid equipment that is involved in this system.

Protective Devices at Work in a Power Grid

First, it’s worth diving into some of the protective devices used on large power grids. When a major fault occurs on a transmission line, it is detected by a sensing device called a relay which can automatically disconnect large breakers, typically within a few cycles of the power system’s base frequency. Disconnecting a fault quickly helps limit or prevent damage to major equipment like transformers or generators. While these relays function in a similar way to a relay that might be used in a car or in an electronics project, they can trigger for things other than current. Overcurrent relays are certainly common, but there are also overvoltage relays, undervoltage relays, frequency relays which can detect over-, under-, or mismatched frequencies in different parts of the grid, as well as a large variety of other types of relays. There are also specifications for time for each of these relays, so a smaller fault will typically take longer to trip a main breaker than a fault with a greater magnitude. Older relays are electromechanical in nature, and typically discrete units (i.e. there will be an overcurrent relay and a frequency relay working together but which are functionally separate units). Newer systems use computers to simplify these functions into single units like this sample from SEL, a company known for their robust digital relays.

With all of these protective relays in virtually every system on the grid, it can get difficult to make sure they all work in harmony together. For example, an overcurrent relay in a power generation station should typically be set at a higher trip setting than the overcurrent relay on a circuit in a downstream substation, so that if a fault were to occur on the transmission line (from a lightning strike, for example) only the substation relay trips the circuit offline, rather than the generator’s relay tripping the entire generation facility offline for a fault which wasn’t in the generation facility at all. Problems like these are known as “coordination” problems and must be solved at every level to prevent nuisance trips and power outages, as well as keep parts of the grid powered up even when other parts are having problems.

Possible Scenarios at Work During This Blackout

With that background in mind, we can look at some of the details of this blackout with some help from a more detailed article in TIME. The article reports that there was a frequency issue of some sort, which may indicate that a frequency-sensitive relay operated when it shouldn’t have, or that it failed to operate when it should have, or was not coordinated properly with other frequency relays. This could have led to the removal of a part of the grid from service that was necessary for stable operation. Maintaining the proper frequency on the power grid is especially difficult. Generators located hundreds or thousands of miles away have to spin at exactly the same speed in exactly the same position in order to avoid causing harmful oscillations on the grid itself. Bringing a large generator online requires synchronization between itself and the grid frequency, and mistakes in this process are unforgiving.

On the other hand, another report of the incident (Google translate from Spanish) claims that high humidity may have caused a fault over an insulator on the transmission system, where electricity was able to follow the moisture around the insulators to cause an overcurrent fault. Disconnecting this much generation capacity may have caused an undervoltage or frequency fault on the grid, starting the cascade. Regardless of initial cause, though, cascades should always be planned for and stopped before they get out of control.

The TIME article also reports that there was some existing damage to transmission lines in the area due to storms, which while not directly responsible for the massive blackout itself could have been a contributing factor. Power grids are particularly susceptible to cascade failure, a type of positive feedback loop where one small failure causes more failures, which in turn cause even more failures. In this case, the damaged transmission lines could have been taken out of service, placing more load on the remaining transmission lines in the area. If an overcurrent fault occurred it would have removed yet another line from service. If greater and greater amounts of electricity start flowing down fewer and fewer lines, the result can be the entire grid tripping offline. This was the case with the 2003 Northeast Blackout in the United States and Canada.

Of course it could have been all of these issues. The frequency may have been the start of the cascade failure, further exacerbated by an already-stressed, damaged transmission line system.

Fast Restoration is Good Sign

Whatever the cause may have been, it is encouraging that the grid operators were able to restore almost all of their customers in less than a day. In blackouts resulting from major damage, like hurricanes and earthquakes, the restoration efforts can take weeks, or in particularly bad situations like Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria repairs can last for months.

The Energy Government Secretariat reports that today at 07: 07hs there was the collapse of the Argentine Interconnection System (SADI), which produced a massive power outage throughout the country that also affected Uruguay. The causes are being investigated and are not yet determined. Recovery has already begun in the regions of Cuyo, NOA and Comahue and the rest of the system is being opened to continue with the total recovery, which is estimated to take a few hours.

From reading update put out by electricity distribution company Edesur during the incident you can see they identified the issue right away, the isolated and eliminated ot quickly in order to ensure that more problems didn’t occur shortly after bringing the power back online. However, risks like this can never be completely eliminated from systems due to the complexity of the grids. Large blackouts continue to occur for many reasons, and in many ways this was a best-case scenario for restoration efforts. Argentina and the surrounding area have a multitude of hydroelectric power stations with blackstart capabilities — able to restart from a total shutdown without needing external power — in turn providing power to other power stations to bring the grid online quickly and reliably. The amount of cooperation across country lines is also impressive in this situation, as five countries are able to operate the grid reliably together every day, facilitate the transportation and sale of electricity across borders, and perform restorations together after a blackout such as this one.

This Could Happen Anywhere

Finally, it’s important to realize that South America’s grid is not fundamentally different from power grids in other parts of the world. Outages like this can occur anywhere, especially if the equipment is aging or poorly maintained. The American Society of Civil Engineers, for example, gives out grades on various parts of infrastructure from time to time and as of 2017 gave the power grid in the United States a D+ grade, citing that most of the grid was built in the 1950s and 1960s with a 50-year life expectancy. The power outage in South America, and other outages like it, may be more of a cautionary tale than an academic curiosity.

Want to learn more about power transmission lines? We have a field guide for that!

No comments:

Post a Comment