Featured in many sci-fi stories as a quicker, more efficient way to record and transfer information, barcodes are both extremely commonplace today, and still amazingly poorly understood by many. Originally designed as a way to allow for increased automation by allowing computer systems to scan a code with information about the item it labels, its potential as an information carrier is becoming ever more popular.

Without the tagging ability of barcodes (and their close cousin: RFID tags), much of today’s modern world would grind to a halt. The automated sorting and delivery systems for mail and parcels, entire inventory management systems, the tracing of critical avionics and rocketry components around the globe, as well as seemingly mundane but widely utilized rapid checkout at the supermarket, all depends on some variety of barcodes.

Join me on a trip through the past, present and future of the humble barcode.

Removing the Human Element

Way back in the 1930s, John Kermode, Douglas Young, and Harry Sparkes of Westinghouse Electric Co were listed as the inventors of an automated card sorter system. This system used a number of bars printed on paper, which would be read by a photo-electric cell, in turn triggering the card (statement, invoice, etc.) to be dropped through a specific trap door, sorting the item into the appropriate bin.

With the goal of the system was to speed up mundane tasks and to reduce the burden of having humans keep track of things like railcars, mail trucks, and other elements in the ever-increasing web of logistics that began to span the USA in the 20th century, automatic equipment identification (AEI) systems such as KarTrak were developed. This system was intended to allow the US railroad to keep track of its rolling stock.

A plate with 13 horizontal labels of varying dimensions and colors was mounted on either side of a car, from where a track side scanner would record the pattern and register the car it was attached to.

Unfortunately, KarTrak’s barcode labels proved to be too unreliable in actual use, with dirt accumulation and damage to the labels being the main reasons why the system was eventually phased out by the late 1970s. These days an RFID-based AEI system is used instead, which is immune to such issues. Cases like these proved that the main limitation of barcodes will always be one of visibility, much as a paper barcode can be damaged, drawn over, or torn off.

This limitation is however not as much of an issue in production environments, warehouses and retail stores, which is where they are most commonly used instead of RFID tags.

Scan It and Bag It

As early as the 1940s, attempts were made to invent a system that would automate parts of the checkout process in grocery stores, especially to look up and tally the prices. In 1948, graduate student Bernard Silver overheard the president of the local Food Fair food chain ask one of the deans to develop a system that would automatically read product information during checkout.

Silver would tell his friend Norman Woodland about this, and together they set out to develop such a system. After an initial failed attempt with ultraviolet ink, Silver would use the basic concept behind Morse code for creating the lines, essentially extending the dots and dashes downwards. Taking a page from the movie industry, he opted to use a photomultiplier tube along with a 500 Watt incandescent light bulb for reading the barcodes.

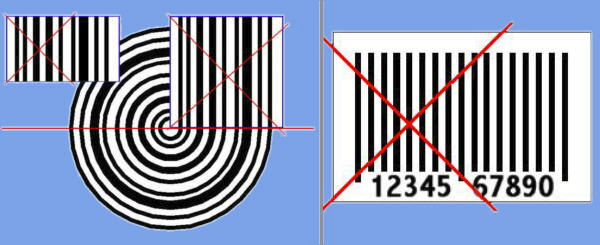

In their 1949 patent application, they described both this linear barcode, as well as a ‘bull’s eye’ version, which Silver deemed would be more efficient and easier to read. When Woodland moved to IBM in 1951, he tried to interest IBM in the system. Though he was successful in this, it was concluded that the technology necessary to make it work was still unavailable at the time.

It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that the topic would come up again, with IBM at Research Triangle Park in North Carolina assigning George Laurer (who sadly passed away in early December of 2019) to lead the team that would go on to create what is now known as the UPC-A barcode. This team consisted of William Crouse (inventor of the Delta C bar code), Heard Baumeister (calculating achievable characters per type of barcode), Norman Woodland (who still worked at IBM) and near the end of the project mathematician David Savir.

Near the end of the project the team was dissolved leading to some glitches in the development effort. Laurer made some changes to the Delta C barcode without applying Baumeister’s equations — making the read error rate skyrocket — but the GS1 retail organization ultimately accepted this Delta C barcode proposed by IBM as the UPC-A Universal Product Code barcode that would go on virtually unchanged to this day.

The most notable change to the system is the Internal Article Number (EAN) superset of UPC-A. EAN adds an extra digit to the beginning of the number, expanding the theoretical number of unique values to one trillion, indicating the country (using GS1 country codes) in which the company selling the product is based. These days essentially all barcodes used in retail are the EAN-13 type.

Enter the Matrix

Although these types of one-dimensional barcodes were and still are very useful, it was realized that by adding a second dimension, one could scale up the amount of information contained in a tag. Helped by improving scanners and ever cheaper CMOS and CCD image sensors, matrix barcodes like the QR code were developed. The QR (‘Quick Response’) code was developed by the Japanese company Denso Wave, back in 1994 (25 years ago) for use in the car industry.

This type of barcode was designed to contain information needed to track vehicles during manufacturing, allowing for rapid scanning using a single frame of image data. By having the position markers at the corners in the matrix barcode, it is easy to determine when one has a complete enough image to parse it.

These days QR codes are used anywhere a smartphone user might need quick access to some kind of information without manually copying strings of characters, including URLs, WiFi network login credentials or arbitrary strings of data. The ability to scan 1D and 2D barcodes is a standard feature of such smartphones, as no extra hardware is required, courtesy of miniature camera technologies one could only dream of back in the 1970s.

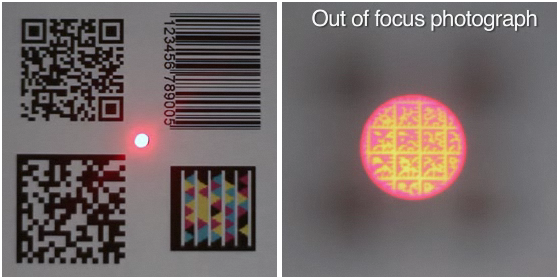

QR codes are obviously not the only type of matrix barcode. Electronic components are often marked with a Data Matrix barcode. This type of matrix barcode allows for very small tags that are readable even in poor lighting conditions. This makes it useful for tracking small components.

This type of barcode is often found on electronic components, on inventory tags, food labels. It can store from a few to up to 1,556 bytes of data, depending on the number of cells in the matrix. This is similar to QR codes, which can be tiny tags (e.g. a 21×21 matrix) or large (e.g. 177×177 matrix) with corresponding physical size.

As can be seen on the WiFi card image, the size of the chosen barcode depends on the amount of information to be encoded. Not only can one scale the barcode itself, the maximum amount of data that can be encoded also depends on the size of the matrix with the overhead from the padding, orientation markings and error correction all having to be taken into account.

As anyone who has ever tried to scan a blurry, damaged, or ridiculously tiny QR code can probably attest, achieving reliable scanning results demand you keep all of those factors in mind. What use is a high-tech matrix barcode after all if it can no longer reveal the data it contains?

Welcome to the Future

Whereas until the 1990s the reliable scanning of barcodes was anything but easy, today’s technologies have made it possible to quite literally put a highly capable 1D and 2D barcode scanner in everyone’s pocket. New technologies have made some look at creating the first 3D barcodes, which would make imprints in a material with 0.4 micron resolution, to be read out with an interferometer setup. This complexity can be used to fight things like counterfeited medication.

The number of 1D and 2D barcodes has quite literally exploded in number, as we noted back in 2015 and again in 2018 when the JAB (Just Another Barcode) joined the party with color instead of black and white markings to increase data depth per dot. Few of them are as insanely awesome as the Bokode tag, however, which takes ‘miniature’ to a whole new level courtesy of advanced optics. Bokodes can also be powered and rewritable, while being readable from up to 4 meters.

With the Wikipedia page for ‘Barcode’ alone listing around a hundred 1D and 2D barcode types, and with many new ones in development, it appears that we may just get that sci-fi future where barcodes are more common than human-readable text. That is, until we finally get those barcode reader upgrades for our cybernetic eyes.

No comments:

Post a Comment