Ever since my RSI surgery, I’ve had to resort to using what I call my compromise keyboard — a wireless rubber dome affair with a gentle curvature to the keys. It’s far from perfect, but it has allowed me to continue to type when I thought I wouldn’t be able to anymore.

This keyboard has served me well, but it’s been nearly three years since the surgery, and I wanted to go back to a nice, clicky keyboard. So a few weeks ago, I dusted off my 1991 IBM Model M. Heck, I did more than that — I ordered a semi-weird hex socket (7/32″) so I could open it up and clean it properly.

And then I used it for half a day or so. It was glorious to hear the buckling springs singing again, but I couldn’t ignore the strain I felt in my pinkies and ring fingers after just a few hours. I knew I had to stop and retire it for good if I wanted to keep being able to type.

Ergo, I Must Go Ergo

I can’t go back to that compromise keyboard, though. It’s got ABS keycaps, and they’re all slick and gross now because that’s what ABS does. The thing is, that keyboard is hurting me in other ways — namely my neck and shoulders. Something this rectangle-keyboard-shaming image doesn’t mention is that the ten-key, or number pad of a standard keyboard makes things worse because of the extra distance to the mouse and back.

For a second, I thought about going back to an original Microsoft Natural keyboard. I used one for many years at my old job, and stopped for the stupidest possible reason — I was tired of the gigantic footprint and wanted more desk space. But honestly, a Natural isn’t going to cut it for me anymore. I need more distance between my hands. I want mechanical switches, and a key layout designed for my needs.

So I started investigating aggressively ergonomic keyboards. Spoiler alert: they’re expensive. And these days, there are all kinds of open-source ergo keyboards out there, which is great to hear if you want to casually fall down the keyboard rabbit hole and make your own. The ErgoDox is a well-documented project with many variants. The one that caught my eye is the Dactyl, which is essentially a bowl-shaped ErgoDox.

Of course I want to make my own, but that will take a while, and I have to keep typing in the meantime. So I had to act fast. While the world of DIY ergo keyboards is mind-boggling, the number of off-the-shelf options is nearly as bad. I’ve never typed on anything crazier than a Microsoft Natural, so how am I supposed to know which one is right for me? Or what keys I would want on the thumb clusters? Which switches? My head was swimming.

Yesterday’s Keyboard of Tomorrow, Today

Fortunately, there’s a company called Kinesis that started making split keyboards with contoured key wells in the early 1990s. You’ve probably seen one and not realized it — there are a bunch of them around the Men In Black headquarters. Kinesis is still making new models for $300+, so you can find older versions starting around $100. I bought the best-looking old one I could find within a few days of searching. Isn’t she a beaut?

I wanted to like this keyboard — heck, I needed to like this keyboard, and I do. There’s no going back now.

Why Is This Better Than a Regular Keyboard?

In a word, ergonomics. And not just the obvious ones, like the split and separated halves that allow me to type without turning my forearms in or hunching over the board. Since the keys are also set into contoured wells, I don’t have to move my fingers or wrists as much, which means less overall strain.

Lined-Up Layout

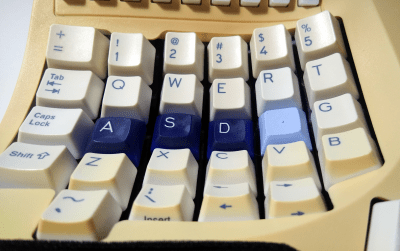

You may have noticed that the key rows aren’t staggered. For instance, 1-Q-A-Z are vertically aligned, which means this layout is considered ortholinear. That in itself can take some getting used to. I had no idea how it would go, but it’s one of the things I was looking forward to about this keyboard. Surprisingly, it doesn’t feel all that different to me, but it depends on your touch typing skills.

You may have noticed that the key rows aren’t staggered. For instance, 1-Q-A-Z are vertically aligned, which means this layout is considered ortholinear. That in itself can take some getting used to. I had no idea how it would go, but it’s one of the things I was looking forward to about this keyboard. Surprisingly, it doesn’t feel all that different to me, but it depends on your touch typing skills.

I consider myself a touch typist in the sense that I don’t need to look at the keys. My typing is not quite textbook, though it’s close. As I waited for this keyboard to arrive, I focused on the fingers I was using and compared them to touch typing diagrams.

My biggest sin is that I use my index finger to type ‘c’, and you’re supposed to use the middle finger. I took an informal poll around the Hackaday dungeon and although a few do it correctly, the index fingers won 11-5. My guess is that it has to do with the brick-wall layout of standard keyboards that places ‘c’ closer to the index.

Under My Thumbs

Under My Thumbs

The best thing about this keyboard has to be the thumb clusters. Moving heavily-used keys like Enter, Backspace, and Control from the pinkies to the thumbs is genius, and has already helped quite a bit.

I have had surprisingly little trouble adjusting to these changes, especially Backspace — it’s as though I’ve been doing it with my left thumb all my life.

Other thumb moves have taken a bit longer to get used to: sometimes I leave my right thumb on Enter instead of moving it back to rest on Space, or I hit Backspace when I really mean Delete. Other than that, I was used to it within a day or so, and started to get back up to speed within a week.

Satisfying Switches

Part of good ergonomics is in the switches. Your modern came-with-the-computer keyboard doesn’t have springs that bounce the keys back toward your fingertips — instead, it either has little rubber domes that collapse and feel like mush, or chiclet keys that are like popping bubble wrap that’s too low-profile to be fun. The only feedback you get is from bottoming out, or pushing the keys down as far as they can go. It may not seem that stressful to your fingertips, but if you’re punching switches all day, the abuse will add up, especially on the weaker fingers.

Mechanical switches aren’t just better for you and more satisfying to type on — they are often rated for millions more key presses than rubber dome and membrane-only switches.

The Model M has good switches, yes, but they take a great deal of actuation force — something like 65 g. The Kinesis Advantage has Cherry MX browns, which only take about 55 g of force, or a stack of eleven United States nickels. Legend has it that Browns were developed especially for Kinesis after they asked Cherry to make a quiet version of their Blue switch. Cherry liked them so much that they eventually started offering them in their own keyboards. Here’s a clip of what they sound like (no, really — I’m not shredding hard drives here):

Browns are tactile and not ridiculously clickykjj, but they definitely have a sound. The Kinesis controller also provides audible feedback for every key press, sort of a gentle ticking sound that can be turned off. I like it, because it makes them feel more like Blues, but without the extra required actuation force. Along with the standard LED indicators, there is audible feedback for Caps/Num/Scroll Lock in the form of two weird robotic buzz-beeps for on, and one for off. Also handy, also turn off-able.

It’s Not Perfect and That’s Okay

It’s Not Perfect and That’s Okay

There are a few things I don’t like about this keyboard. Some I’ve already taken care of, and some are fueling my desire to build my own.

The home row keys are a different color (which is awesome), but they don’t have those little homing bumps on them like you can find on literally any cheap keyboard. Instead, the home row keycaps are sculpted differently than the rest. This might work for some people, but my callused fingertips can’t really tell the difference, so I got some aftermarket blanks with homing bumps for F and J.

Unfortunately, all the keycaps except for F and J are ABS, so they will get shiny and gross eventually. Not only that, the legends are pad printed, so they’re like little stickers you can feel and pick at that will definitely disappear given enough time and fingernail contact.

I thought I would miss the ten-key more than I do, although there is a ten-key embedded in the right side that’s accessible with the Keypad F-row button. Mostly what I miss is the ten-key Enter, because it’s right there by the mouse. But it’s okay, because I can reprogram it!

Since I was never a right-Shifter and I recently started using a foot pedal for it anyway, I took five seconds and copy-pasted the Enter key on to the right Shift, right by the mouse. Sometimes I even remember to use it.

Do You Really Own Your Keyboard?

If all you can do to change things is toggle Caps Lock, Num Lock, and Scroll Lock, then I would say no. This keyboard is fully programmable, meaning you can switch a few keys around or go full Dvorak if you want. You can also program macros into the F keys. With the Advantage 2, this is all done through an editor.

Unfortunately, the Kinesis’ portability ends there. Yes it’s lightweight, and no it’s not that big (16.5″ x 8″), but if you want to throw it in a backpack, you’d better have a pretty big one. I’m already dreaming of being able to put my hands even farther apart with a split keyboard.

There are tons of open-source alternatives to drool over, thanks to the 2010s boom in mechanical keyboard interest. Many of them use firmware like QMK that allows for layers of key functions, so you’ll see minimal, highly customized, perfectly portable builds.

I’ve got my eye on building a Dactyl Manuform, which is like a liberated Kinesis with even more ergonomic thumb cluster design. It kind of has to be hand-wired, which I’m actually looking forward to — flex PCBs would be too fiddly. Just have to get the halves printed and I’ll be on my way to split ergo freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment