When you put a human driver behind the wheel, they will use primarily their eyes to navigate. Both to stay on the road and to use any navigation aids, such as maps and digital navigation assistants. For self-driving cars, tackling the latter is relatively easy, as the system would use the same information in a similar way: when to to change lanes, and when to take a left or right. The former task is a lot harder, with situational awareness even a challenge for human drivers.

In order to maintain this awareness, self-driving and driver-assistance systems use a combination of cameras, LIDAR, and other sensors. These can track stationary and moving objects and keep track of the lines and edges of the road. This allows the car to precisely follow the road and, at least in theory, not run into obstacles or other vehicles. But if the weather gets bad enough, such as when the road is covered with snow, these systems can have trouble coping.

Looking for ways to improve the performance of autonomous driving systems in poor visibility, engineers are currently experimenting with ground-penetrating radar. While it’s likely to be awhile before we start to see this hardware on production vehicles, the concept already shows promise. It turns out that if you can’t see whats on the road ahead of you, looking underneath it might be the next best thing.

Knowing Your Place in the World

Certainly the biggest challenge of navigating with a traditional paper map is that it doesn’t provide a handy blinking icon to indicate your current location. For the younger folk among us, imagine trying to use Google Maps without it telling you where you are on the map, or even which way you’re facing. How would you navigate across a map, Mr. Anderson, if you do not know where you are?

This is pretty much an age-old issue, dating back to the earliest days of humanity. Early hunter-gatherer tribes had to find their way across continents, following the migratory routes of their prey animals. They would use landmarks and other signs that would get passed on from generation to generation, as a kind of oral map. Later on, humans would learn to navigate by the stars and Sun, using a process called celestial navigation.

Later on, we’d introduce the concept of longitude and latitude to divide the Earth’s surface into a grid, using celestial navigation and accurate clocks to determine our position. This would remain the pinnacle of localization and a cornerstone of navigation until the advent of radio beacons and satellites like the GPS constellation.

So it might seem like self-driving vehicles could use GPS to determine their current location, skipping the complicated sensors and not not bothering to look at the road at all. In a perfect world, they could. But in practice, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Precision is a Virtue

The main issue with a systems like GPS is that accuracy can vary wildly depending on factors such as how many satellites are visible to the receiver. When traveling through wide open country, one’s accuracy with a modern, L5-band capable GPS receiver can be as good as 30 centimeters. But try it in a forest or a city with tall buildings that reflect and block the satellite signals, and suddenly one’s accuracy drops to something closer to 5 meters, or worse.

It also takes time for a GPS receiver to obtain a “fix” on a number of satellites before it can determine its location. This isn’t a huge problem when GPS is being used to supplement position data, but it could be disastrous if it was the only way a self-driving vehicle knew where it was. But even in perfect conditions, GPS just doesn’t get you close enough. The maximum precision of 30 centimeters, while more than sufficient for general navigation, could still mean the difference between being on the road and driving off the side of it.

One solution is for self-driving vehicles to adopt the system that worked for our earliest ancestors, using landmarks. By having a gigantic database of buildings, mountains and other landmarks of note, cameras and LIDAR systems could follow a digital map so the car always has a good idea of where it is. Unfortunately, such landmarks can change relatively quickly, with buildings torn down, new buildings erected, a noise barrier added along a stretch of highway, and so on. Not to mention the impact of poor weather and darkness on such systems.

The Good Kind of boring

When you think about it, what’s below our feet doesn’t change a great deal. Once a road goes down, not too much will happen to whatever is below it. This is the reasoning behind the use of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) with vehicles, in what is called localizing ground-penetrating radar (LGPR). MIT has been running experiments on the use of this technology for a few years now, and recently ran tests with having LGPR-equipped vehicles self-navigate in both snowy and rainy conditions.

They found that the LGPR-equipped system had no trouble staying on track, with snow on the road adding an error margin of only about 2.5 cm (1″), and a rain-soaked road causing an offset of on average 14 cm (5.5″). Considering that their “worst case” findings are significantly better (by about 16 cm) than GPS on a good day, it’s easy to see why there’s so much interest in this technology.

Turning Cars into Optical Mice

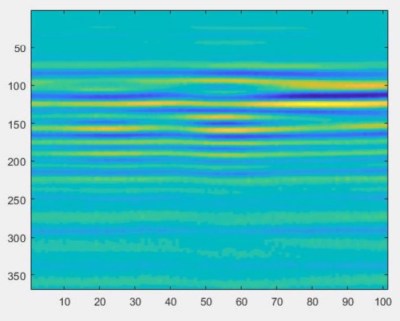

The GPR system sends out electromagnetic pulses in the microwave band, where layers in the ground will impact how and when these pulses will be reflected, providing us with an image of the subsurface structures.

This isn’t unlike how an optical mouse works, where the light emitted from the bottom reflects off the surface it’s moving on. The mouse’s sensor receives a pattern of reflected light that allows it to deduce when it’s being moved across the desk, in which direction, and how fast.

LGPR is similar, only in addition to keeping track of direction and speed, it also compares the image it records against a map which has been recorded previously. To continue the optical mouse example, if we were to scan our entire desk’s surface with a sensor like the one in the mouse and perform the same comparison, our mouse would be able to tell exactly where it is on the desk (give or take a few millimeters) at all times.

Roads would be mapped in advance by a special LGPR truck, and this data would be provided to autonomous vehicles. They can then use these maps as reference while they move across the roads, scanning the subsurface structures using their LGPR sensors to determine their position.

Time will Tell

Whether or not this LGPR technology will be the breakthrough that self-driving cars needed is hard to tell. No matter what, autonomous vehicles will still need sensors for observing road markings and signs because above ground things change often. With road maintenance, traffic jams, and pedestrians crossing the street, it’s a busy world to drive around in.

A lot of the effort in making autonomous vehicles “just work” depends less on sensors, and more on a combination of situational awareness and good decision making. In the hyper-dynamic above ground world, there are countless times during even a brief grocery shopping trip that one needs to plan ahead, take rapid decisions based on sudden events, react to omissions in one’s planning, and deal with other traffic both by following the rules and creatively adapting said rules when others take sudden liberties.

With a number of autonomous vehicles on the roads from a wide variety of companies, we’re starting to see how well they perform in real-life situations. Here we can see that autonomous vehicles tend to be programmed in a way that makes them respond very conservatively, although adding a bit more aggression might better fit the expectations of fellow (human) drivers.

Localizing ground-penetrating radar helps by adding to the overall situational awareness, but only if somebody actually makes the maps and occasionally goes back to update them. Unfortunately that might be the biggest hurdle in rolling out such a system in the real world, since the snow-covered roads where LGPR could be the most helpful are likely the last ones to get mapped.

No comments:

Post a Comment