In the recent frenzy of stocking up with provisions as the populace prepare for their COVID-19 lockdown, there have been some widely-publicised examples of products that have become scarce commodities. Toilet paper, pasta, rice, tinned vegetables, and long-life milk are the ones that come to mind, but there’s another one that’s a little unexpected.

As everyone dusts off the breadmaker that’s lain unused for years since that time a loaf came out like a housebrick, or contemplates three months without beer and rediscovers their inner home brewer, it seems yeast can’t be had for love nor money. No matter, because the world is full of yeasts and thus social media is full of guides for capturing your own from dried fruit, or from the natural environment. A few days tending a pot of flour and water, taking away bacterial cultures and nurturing the one you want, and you can defy the shortage and have as much yeast as you need.

More Than Just A Supermarket Product Line

Everyone enjoys the odd crusty loaf or foaming pint. The yeast that make this possible is an interesting technical subject in its own right that makes a significant entry into the hacker community. There’s a lot more to it than just the sachets of baker’s yeast in the supermarket ingredients aisle and if you know what you’re doing you can snag it out of thin air.

Yeast cultivation is a subject in which I have more than a passing interest, because ever since I was a teenager I have made my own real cider. For years the quality of the yeast that ferments my juice has been of great concern to me, sometimes it’s gone wrong and I’ve gone to considerable lengths in other years to ensure I have the right strains.

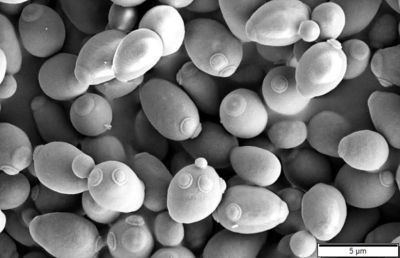

Yeasts are single-cellular fungi, and just as with any other class of organisms there are many varieties present in the wild. Some can be found widely, while others are specific to particular environments or situations. Finding them is easy enough, they are so widely dispersed that they are present in some form almost everywhere, and the air you breathe probably contains significant numbers of yeast spores which are the source of some of the natural yeast cultures shared by those people on social media. I’m no expert in species taxonomy, but the type of yeasts we are interested in all belong to the Saccharomyces family, which the sharp-eyed will recognise as containing the Ancient Greek words for “sugar” and “fungus”.

The Hackaday Strain

Thanks to a liking for home-made pizza, we already had a pack of dried yeast in our cupboard here. But what if we hadn’t? It was time to put all that natural yeast cidermaking experience to the test. Into the store cupboard for some dried fruit and plain flour, and into the recycling bin for a jam jar with a lid. This was cleaned with some boiling water, and then a spoonful of currants were shaken up in it with some water. Immediately I could see some yeast had come off the currants, because the water was cloudy.

The process of turning cloudy currant water into a usable yeast culture is a slow and annoying one. The idea is to mix it up with some flour to serve as food and put it in a warm place, then once you can see the tell-tale bubbles and yeasty smell to indicate it’s started going, separate a small quantity of it with some fresh flour and water to make a new culture in a new container. Doing this several times over is designed to produce an environment that favours the yeast and reduces the chance of any bacterial cultures taking hold. It’s slow because wild yeasts take their time to get going, I’ve had wild yeast ciders that have sat for several days before fermentation kicks off.

Eventually though, if you are persistent you’ll have a big frothy mass of yeast that you can feed with sugar just as you would if you were activating dried yeast for baking or brewing. At the time of writing the Hackaday Strain is on its second new culture, and is starting to look as though it might have enough in it to be used for a pizza later in the week. A Core i7 desktop computer running Folding@Home provides plenty of warmth to incubate it. It’s important to point out though, that whatever yeast you might culture in this way will be a random variety depending on whatever you used to start it. If you’re lucky it’ll produce amazing bread and fine wines, if not you might need to give it another try.

Let’s Get Down To Varieties And Strains

The yeasts that you will capture if you create your own culture are likely to contain more than one variety, but the commercial yeasts you buy will have been carefully grown as a monoculture. The yeast used in baking, in brewing ale, and in wine and cider making are all different strains of the same variety, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is a yeast that thrives at a higher temperature. Thus when you make bread you leave it in a warm place for proving, and when you brew an ale you will warm the wort slightly for the best result. In both cases the fermentation is anaerobic resulting in the production of alcohol and carbon dioxide, and when it is in a liquid it floats to the top. thus ales are sometimes referred to as top-fermenting. It’s possible to brew ale with baker’s yeast, and though I’ve never done it, it’s no doubt possible to make bread with the corresponding beer strain.

So having identified the protagonist in the making of both bread and ale, we might consider ourselves to be done, right? Perhaps some of you have noticed that I’ve used the word “ale” so far rather than “beer”, because of course top-fermenting ale is not the only type of beer. The word “lager” is rather misused in some English-speaking countries to mean a beer in the pale Pilsener style, but in fact “lager” from the practice of storing the brew in caves to mature, refers collectively to an entire class of beers fermented with an entirely different yeast variety. Saccharomyces pastorianus is a natural hybrid between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and another wild species, and ferments at a much lower temperature with the yeast settling to the bottom of the wort. These bottom-fermenting beers come in every bit as diverse a range of styles as their ale equivalents, leaving the mass-market “lagers” such as Budweiser or Carling a poor representation.

There is a third type of yeast culture that is commonly used in the making of bread, so-called sourdough. This is a mixture of yeast, usually Saccharomyces exiguous, and lactobacillus, yielding a fermentation that produces the lactic acid that gives the sourdough loaf its characteristic flavour. This yeast is tolerant of acidity, whereas Saccharomyces cerevisiae would die in the same situation.

I hope that this short introduction has given you a basic primer in the world of yeast, and that if you’re stuck for something to do while on lockdown you can at least try your hand at bread or beer without having to find a yeast sachet on those empty shelves. I didn’t have any hops, so I’ve got a batch of something new to me on the go: spruce ale. Good luck with whatever you try, and enjoy the fruits of your labour!

Header image: Jon Sullivan / Public domain.

No comments:

Post a Comment