Because of the architecture used for the Apollo missions, extended stays on the surface of the Moon weren’t possible. The spartan Lunar Module simply wasn’t large enough to support excursions of more than a few days in length, and even that would be pushing the edge of the envelope. But then the Apollo program was never intended to be anything more than a proof of concept, to demonstrate that humans could make a controlled landing on the Moon and return to Earth safely. It was always assumed that more detailed explorations would happen on later missions with more advanced equipment and spacecraft.

Now NASA hopes that’s finally going to happen in the 2020s as part of its Artemis program. These missions won’t just be sightseeing trips, the agency says they’re returning with the goal of building a sustainable infrastructure on and around our nearest celestial neighbor. With a space station in lunar orbit and a permanent outpost on the surface, personnel could be regularly shuttled between the Earth and Moon similar to how crew rotations are currently handled on the International Space Station.

Naturally, there are quite a few technical challenges that need to be addressed before that can happen. A major one is finding ways to safely and accurately deliver multiple payloads to the lunar surface. Building a Moon outpost will be a lot harder if all of its principle modules land several kilometers away from each other, so NASA is partnering with commercial companies to develop crew and cargo vehicles that are capable of high precision landings.

But bringing them down accurately is only half the problem. The Apollo Lunar Module is by far the largest and heaviest object that humanity has ever landed on another celestial body, but it’s absolutely dwarfed by some of the vehicles and components that NASA is considering for the Artemis program. There’s a very real concern that the powerful rocket engines required to gracefully lower these massive craft to the lunar surface might kick up a dangerous cloud of high-velocity dust and debris. In extreme cases, the lander could even find itself touching down at the bottom of a freshly dug crater.

Of course, the logical solution is to build hardened landing pads around the Artemis Base Camp that can support these heavyweight vehicles. But that leads to something of a “Chicken and Egg” problem: how do you build a suitable landing pad if you can’t transport large amounts of material to the surface in the first place? There are a few different approaches being considered to solve this problem, but certainly one of the most interesting among them is the idea proposed by Masten Space Systems. Their experimental technique would allow a rocket engine to literally build its own landing pad by spraying molten aluminum as it approaches the lunar surface.

Practice Makes Perfect

While Masten might not be a household name, they aren’t exactly neophytes when it comes to landing rockets. In fact, it’s their specialty. Founded in 2004, the company has been working on a series of increasingly powerful vertical-takeoff, vertical-landing (VTVL) vehicles that have cumulatively performed over 600 flights. The latest version, the XL-1, has been selected as part of NASA’s Lunar CATALYST program to deliver multiple payloads to the Moon’s South Pole by 2022.

After more than a decade of developing rocket-powered landers in the Mojave Desert, Masten is well aware of the dangers posed by the high velocity ejecta that gets kicked up right before touchdown. They’ve found that the easiest solution is to simply add enough shielding to the bottom of the craft that soil and rocks will bounce off without doing any damage. But it doesn’t scale well, as every bit of shielding you add to the vehicle reduces its useful payload capacity.

Besides, even if you armor the lander to the point that ejected materials wouldn’t cause it any damage, it would still be boring a hole into the ground on each landing. It would still endanger nearby vehicles and structures as well; a serious problem for all but the very first missions. Because of this, Masten started researching the way the lunar surface will behave when exposed to the force of their landing engines.

It’s impossible to completely simulate lunar conditions here on Earth, as there’s no way to reduce the effect of gravity on the material blown out by the rocket’s exhaust. But their terrestrial testing was enough to convince them that they should start investigating different ways to combat the issue.

Instant Landing Pad, Just Add Heat

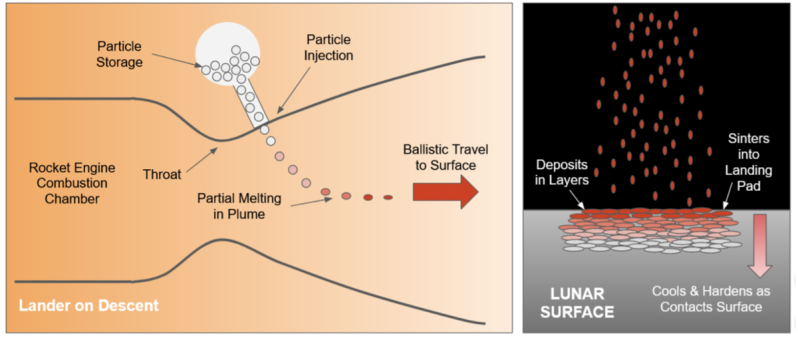

Masten’s concept is called the FAST, or the in-Flight Alumina Spray Technique. To use FAST, the lander would descend to within a few meters of the Moon’s surface and go into a controlled hover. Aluminium oxide (also known as alumina) pellets would then be injected into the rocket’s exhaust, where they are melted and ejected downwards. Once the alumina hits the lunar regolith, it combines with the loose material and behinds to cool and solidify.

By slowly moving over the landing site, the engine can deposit a thick enough layer of molten alumina to create a custom landing pad of whatever dimensions are required. After its completely hardened, the Masten proposal says it should have sufficient thermal and abrasion resistance for the vehicle to complete its decent without kicking up any dust or forming a crater.

Or at least, that’s the idea. Injecting solid particles into the exhaust plume of a running rocket engine is relatively unexplored territory, and it will be interesting to see what Masten finds. Will adjustments will be required to maintain stable thrust during the hover maneuver? Is there a risk that the alumina might build up inside the engine? Could it clog the engine so that relighting it becomes impossible?

The company says they will spend the next nine months researching these questions, and likely many more, before making a final decision about whether or not the technology is worth pursuing for the Artemis program. Even if it’s not ready in time for the 2022 – 2024 landings that NASA says will be the first steps towards a sustainable program of lunar exploration, the company believes the idea could still be used when the agency turns its attention to Mars in the 2030s and beyond.

No comments:

Post a Comment