Just to intensify the feeling of impending zombie apocalypse of the COVID-19 lockdown in the British countryside where I live, we had a power cut. It’s not an uncommon occurrence here at the end of a long rural power distribution network, and being prepared for a power outage is something I wrote about a few years ago. But this one was a bit larger than normal and took out much more than just our village. I feel very sorry for whichever farmer in another village managed to collide with an 11kV distribution pole.

What pops to mind for today’s article is the topic of outage monitoring. When plunged into darkness we all wonder if the power company knows about it. The most common reaction must be: “of course the power company knows the power is out, they’re the ones making it!”. But this can’t be the case as for decades, public service announcements have urge us to report power cuts right away.

In our very modern age, will the grid become smart enough to know when, and perhaps more importantly where, there are power cuts? Let’s check some background before throwing the question to you in the comments below.

A Power Cut On A Sunny Afternoon

In the aftermath I was discussing it among my neighbours, and a difference of opinion emerged over whether our electricity provider has automatic monitoring of their network or whether we need to call a fault in.

It seems the power company operators had issued the advice that there was no monitoring, but my mind had gone back to a summer afternoon in the mid 1990s. Our then neighbour was a lifelong farmer with decades of conjuring a decent yield from the unforgiving heavy Oxfordshire clay behind him, but that was not his lucky day. The long CB whip antenna on the roof of one of his machines touched the village’s 11kV supply line, and our power went out. I never saw what it did to the unfortunate CB transceiver, but I remember him talking about his surprise as when he reached the farmhouse to call it in he found the electricity people calling him instead. Their monitoring equipment had detected the fault and narrowed it down to his property.

But the power people here in 2020 told my current neighbour we have none, and it’s obvious both can’t be true. It’s most likely that they have it on some circuits but not others, but that guess doesn’t really put the whole question to bed.

It’s easy to be certain that there is no power monitoring equipment on any of the poles in our village, by simply looking at them and seeing no untoward equipment in place. We’re in the midst of a nationwide rollout of smart meters so it’s possible that if any of our neighbours have one it might have called home over the cellular data network and alerted their operators to the loss of power. But since the rollout is optional and there is no compulsion on a consumer to have one it’s by no means certain that there are any in the village. It’s thus safe to assume that any power monitoring equipment is centralised rather than distributed. And with that it’s a reasonable guess that some form of time-domain reflectometry would be in use.

Bouncing Pulses Along Your Power Lines

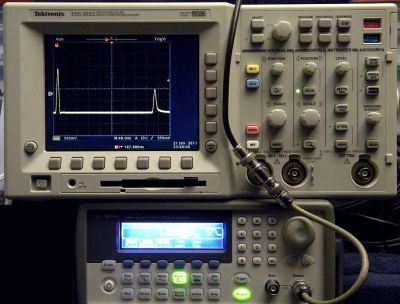

Time domain reflectometry is an extremely simple process that relies on the property of a traveling waveform to bounce off the end of a transmission line and be reflected back to its originator. It’s a standard lab experiment for electronic engineering students that can easily be replicated with a pulse generator, a coil of cable, and an oscilloscope. Adjust the ‘scope to see the end of the generated pulse, and there a short time later will be its reflection. The time between the end of the sent pulse and the arrival of the reflection is the time it has taken to travel the length of the cable and back again, so from that the length of the cable can be calculated.

Since the pulse will reflect from any faults, the distance to the fault can also be worked out. Once the breaker has been triggered by the fault the electricity company can measure the distance, and send out a repair team to fix it. That’s exactly how an El Segundo steam plant located a fault in ten miles of buried cable.

So goes the theory, but something tells me that even with state-of-the-art equipment it is unlikely to be that simple. For example, is our 11kV power distribution to the 230V transformer in the village a linear one in which a succession of farms and groups of houses as it gets further from the substation tap in with their own transformers, or is it a branched topology in which the line splits, and splits again? Time domain reflectometry would be useless when there are multiple ends of the line. Is the only way to deal with that by waiting for a human (or a smart meter) to phone home?

I’m told mains electricity finally arrived in this village in the 1950s, so I am fortunate to be of a generation for whom it has always been there. It’s so much part of the scenery that we don’t really notice it and certainly don’t appreciate the effort that must lie behind it, so I’m slightly ashamed as an electronic engineer that I don’t know more about its technology. Power engineers, now is your time to shine, and tell us something about your art!

Satisfy my curiosity, Hackaday, what’s the current State of the Art when it comes to automatic power distribution system monitoring? Share your stories in the comments below.

No comments:

Post a Comment