The SD card first burst onto the scene in 1999, with cards boasting storage capacities up to 64 MB hitting store shelves in the first quarter of 2000. Over the years, sizes slowly crept up as our thirst for more storage continued to grow. Fast forward to today, and the biggest microSD cards pack up to a whopping 1 TB into a package smaller than the average postage stamp.

However, getting to this point has required many subtle changes over the years. This can cause havoc for users trying to use the latest cards in older devices. To find out why, we need to take a look under the hood at how SD cards deal with storage capacity.

Initial Problems

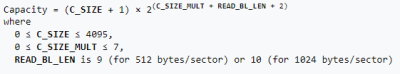

The first issues began to appear with the SD standard as cards crossed the 1 GB barrier. Storage in an SD card is determined by the number of clusters, how many blocks there are per cluster, and how many bytes there are per block. This data is read out of the Card Specific Data, or CSD register, by the host. The CSD contains two fields, C_SIZE, and C_SIZE_MULT, which designated the number of clusters and number of blocks per cluster respectively.

The 1.00 standard allowed a maximum of 4096 clusters and up to 512 blocks per cluster, while assuming block size was 512 bytes per block. 4096 clusters multiplied by 512 blocks per cluster, multiplied by 512 bytes per block, gives a card with 1 GB storage. At this level, there were no major compatibility issues.

The 1.01 standard made a seemingly minor change – allowing the block size to be 512, 1024, or even 2048 bytes per block. An additional field was added to designate the maximum block length in the CSD. Maximum length, as designed by READ_BL_LEN and WRITE_BL_LEN in the official standard, could be set to 9, 10, or 11. This designates the maximum block size as 512 bytes (default), 1024 bytes, or 2048 bytes, allowing for maximum card sizes of 1 GB, 2 GB, or 4 GB respectively. Despite the standard occasionally mentioning maximum block sizes of 2048 bytes, officially, the original SD standard tops out at 2 GB. This may have been largely due to the SD card primarily being intended for use with the FAT16 file system, which itself topped out at a 2 GB limit in conventional use.

Suddenly, compatibility issues existed. Earlier hosts that weren’t aware of variable block lengths would not recognise the greater storage available on the newer cards. This was especially problematic with some edge cases that tried to make 4 GB cards work. Often, very early readers that ignored the READ_BL_LEN field would report 2 GB and rare 4 GB cards as 1 GB, noting the correct number of clusters and blocks but unable to recognise the extended block lengths.

Thankfully, this was still early in the SD card era, and larger cards weren’t in mainstream use just yet. However, with the standard hitting a solid size barrier at 4 GB due to the 32-bit addressing scheme, further changes were around the corner.

Later Barriers

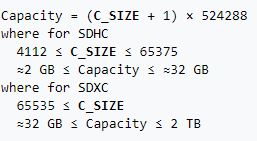

2006 brought about version 2.00 of the SD specification. Heralding in the SDHC standard, it promised card sizes up to a full 32GB. Technically, SDHC was treated as a new standard, meaning all cards above 2GB should be SDHC, while cards 2GB and below should remain implemented as per the existing SD standard.

To achieve these larger sizes, the CSD register was entirely reworked for SDHC cards. The main C_SIZE field was expanded to 22 bits, indicating the number of clusters, while C_SIZE_MULT was dropped, with the standard assuming a size of 1024 blocks per cluster. The field indicating block length – READ_BL_LEN – is kept, but locked to a value of 9, mandating a fixed size of 512 bytes per block. Two formerly reserved bits are used to indicate card type to the host, with standard SD cards using a value of 0, with a 1 indicating SDHC format (or later, SDXC). Sharp readers will note that this could allow for capacities up to 2 TB. However, the SDHC standard officially stops at 32 GB. SDHC also mandates the use of FAT32 by default, giving the cards a hard 4 GB size limit per file. In practice, this is readily noticable when shooting long videos at high quality on an SDHC card. Cameras will either create multiple files, or stop recording entirely when hitting the 4 GB file limit.

To go beyond this level, the SDXC standard accounts for cards greater than 32 GB, up to 2 TB in size. The CSD register was already capable of dealing with capacities up to this level, so no changes were required. Instead, the main change was the use of the exFAT file system. Created by Microsoft especially for flash memory devices, it avoids the restrictive 4 GB file size limit of FAT32 and avoids the higher overheads of file systems like NTFS.

Current cards are available up to 1 TB, close to maxing out the SDXC specification. When the spec was announced 11 years ago, Wired reported that 2 TB cards were “coming soon”, which in hindsight may have been jumping the gun a bit. Regardless, the next standard, SDUC, will support cards up to 128 TB in size. It’s highly likely that another break in compatibility will be required, as the current capacity registers in the SDXC spec are already maxed out. We may not find out until the specification is made available to the wider public in coming years.

Where The Problems Lie

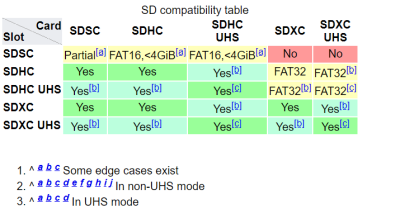

The most obvious compatibility problems lie at the major barriers between generations of SD cards. The 1 GB barrier between 1.00 and 1.01, the 2 GB barrier between SD and SDHC, and the 32GB barrier between SDHC and SDXC. In most embedded hardware, these are hard barriers that simply require the correct size card or else they won’t work at all. However, in the case of desktop computers, there is sometimes more leeway. As an example, SanDisk claim that PC card readers designed to handle SDHC should be able to read SDXC cards as well, as long as the hosting OS also supports exFAT. This is unsurprising, given the similar nature of the standards at the low level.

Thankfully, newer readers are backwards compatible with older cards, but the reverse is rarely true. However, workarounds do exist that can allow power users to make odd combinations play nice. For example, formatting SDXC cards with FAT32 generally allows them to be used in place of SDHC cards. Additionally, formatting SDHC cards with FAT16 may allow them to be used in place of standard SD cards, albeit without access to their full storage capacity.

These workarounds are far from a sure thing, though. Many devices exist that have their own baked-in limits, from quirks in their own hardware and software. A particularly relevant example is the Raspberry Pi. All models except for the 3A+, 3B+ and Compute Module 3+ are limited to SD cards below 256 GB, due to a bug in the System-on-Chip of earlier models. Fundamentally, for some hardware, the best approach can be to research what works and what doesn’t, and be led by the knowledge of the community. Failing that, buy a bunch of cards, write down what works and what doesn’t, and share the results for others to see.

Unfortunately, the problem isn’t going away anytime soon. If anything, as card sizes continue to increase, older hardware may be left behind as it becomes difficult to impossible to source compatible cards in smaller capacities that are no longer economical for companies to make. Already, it’s difficult to impossible to source new cards 2 GB and below. Expect complicated emulated solutions to emerge for important edge-case hardware, in the same way we use SD cards to emulate defunct SCSI disks today.

No comments:

Post a Comment