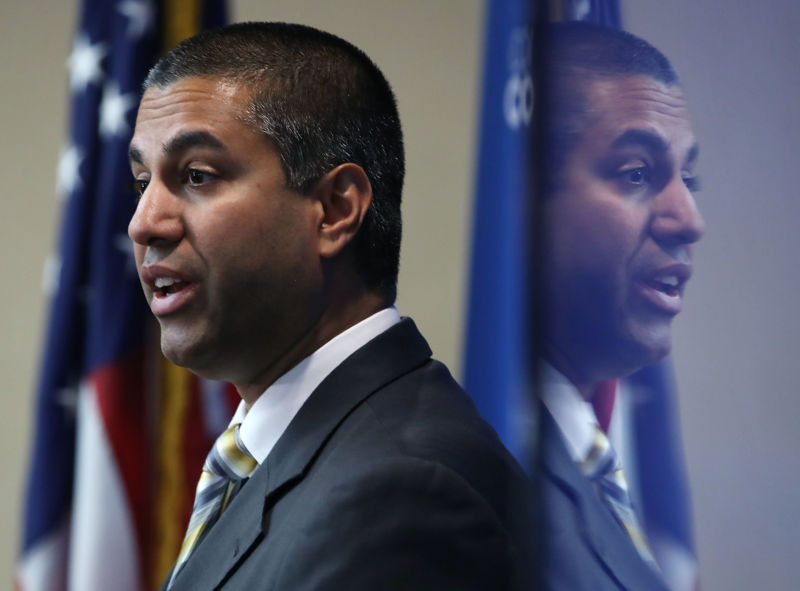

Enlarge / Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch, back, and Stephen Breyer, right, seemed skeptical of the government's broad reading of the CFAA. Justice Thomas, center, seemed more sympathetic to the government's view. Chief Justice Roberts, left, kept his cards close to his chest. (credit: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The Supreme Court on Monday considered how broadly to interpret the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, America's main anti-hacking statute.

Here's how I described the case back in September:

The case arose after a Georgia police officer named Nathan Van Buren was caught taking a bribe to look up confidential information in a police database. The man paying the bribe had met a woman at a strip club and wanted to confirm that she was not an undercover cop before pursuing a sexual—and presumably commercial—relationship with her.

Unfortunately for Van Buren, the other man was working with the FBI, which arrested Van Buren and charged him with a violation of the CFAA. The CFAA prohibits gaining unauthorized access to a computer system—in other words, hacking—but also prohibits "exceeding authorized access" to obtain data. Prosecutors argued that Van Buren "exceeded authorized access" when he looked up information about the woman from the strip club.

But lawyers for Van Buren disputed that. They argued that his police login credentials authorized him to access any data in the database. Offering confidential information in exchange for a bribe may have been contrary to department policy and state law, they argued, but it didn't "exceed authorized access" as far as the CFAA goes.

Obviously, no one is going to defend a cop allegedly accepting bribes to reveal confidential government information. But the case matters because the CFAA has been invoked in prosecutions of more sympathetic defendants. For example, prosecutors used the CFAA to prosecute Aaron Swartz for scraping academic papers from the JSTOR database. They also prosecutied a small company that used automated scraping software to purchase and resell blocks of tickets from the TicketMaster website.