It is popular to blame new technology for killing things. The Internet killed newspapers. Video killed the radio star. Is FT8, a new digital technology, poised to kill off ham radio? The community seems evenly divided. In an online poll, 52% of people responding says FT8 is damaging ham radio. But ham operator [K5SDR] has an excellent blog post about how he thinks FT8 is going to save ham radio instead.

If you already have an opinion, you have probably already raced down to the comments to share your thoughts. I’ll be honest, I think what we are seeing is a transformation of ham radio and like most transformations, it is probably both killing parts of ham radio and saving others. But if you are still here, let’s talk a little bit about what’s going on in ham radio right now and how it relates to the FT8 question. Oddly enough, our story starts with the strange lack of sunspots that we’ve been experiencing lately.

Classic Ham Radio

I’ve been a ham radio operator since 1977. The hobby has changed a lot over the years. I can remember as a teenager making a phone call from my car and everyone was amazed. Ham radio covers a lot of ground, but “traditional” ham radio is operating a station on the HF bands — 3.5 MHz to 30 MHz — and talking to people all over the world. That kind of ham radio is suffering right now for a few reasons. First, HF propagation largely depends on sunspots and sunspots tend to ebb and peak on an 11-year cycle. Right now we are in a deep low part of the cycle and even the last few peaks have not been very good and no one knows why.

I’ve often thought that if Marconi and the others had started experimenting with radio during a sunspot low, they might have decided radio wasn’t very practical. With low sunspot activity, higher frequencies don’t propagate well at all. Lower frequencies might get through, but those require much larger antennas and that causes another problem.

At the height of classic ham radio, every ham wanted a beam antenna or a cubical quad or some other type of rotating directional antenna. Being able to swing an antenna at a particular direction brings more power to bear on the receiver and also helps you receive the other station. The problem is, the antenna elements are typically about a half wavelength in size. So at 20 meters, the elements are about 10 meters in size. You can shorten them a little using some tricks but you pay a price for that in performance. At 10 meters, though, the size is quite manageable. Many hams had directional antennas for the 20, 15, and 10 meter bands (all-in-one antennas called tribanders). A very few would have something for 40 meters — despite Mosley’s description of its 40-20-15 antenna as “vest pocket”, but that was pretty exotic. At 80 meters, mechanically rotating directional antennas are all but unheard of.

At the height of classic ham radio, every ham wanted a beam antenna or a cubical quad or some other type of rotating directional antenna. Being able to swing an antenna at a particular direction brings more power to bear on the receiver and also helps you receive the other station. The problem is, the antenna elements are typically about a half wavelength in size. So at 20 meters, the elements are about 10 meters in size. You can shorten them a little using some tricks but you pay a price for that in performance. At 10 meters, though, the size is quite manageable. Many hams had directional antennas for the 20, 15, and 10 meter bands (all-in-one antennas called tribanders). A very few would have something for 40 meters — despite Mosley’s description of its 40-20-15 antenna as “vest pocket”, but that was pretty exotic. At 80 meters, mechanically rotating directional antennas are all but unheard of.

So when propagation is bad you should go to lower frequencies, but that means larger antennas. Worse still, the last few decades have seen an increasing hostility to ham radio antennas with city governments, home owner’s associations, and similar. People living in apartments or condos have the same kind of problem. So the number of hams who can even put up a tribander or any sort of visible antenna has dropped significantly.

So here you are with your radio. The bands are bad, and your small hidden antenna is not very good at any band that might work. What do you do?

Voice is Wasteful

One historical answer to this problem was to quit talking and start using Morse code. For a variety of reasons, Morse code will get through when there isn’t enough power, antennas, or propagation to send voice communications. A skilled operator can pull a Morse code signal out of noise that you would swear is just noise. But what if you aren’t a skilled operator? Bring in a skilled computer.

One historical answer to this problem was to quit talking and start using Morse code. For a variety of reasons, Morse code will get through when there isn’t enough power, antennas, or propagation to send voice communications. A skilled operator can pull a Morse code signal out of noise that you would swear is just noise. But what if you aren’t a skilled operator? Bring in a skilled computer.

Some hams have always experimented with digital operation, mostly with war-surplus teletype machines. Sending data digitally is almost as good as sending Morse code and it is easy to type and read a printout compared to manually sending and receiving code. Sure, computers can read code, but since a human is sending it, it is likely to not be perfect copy unless the software is very smart and can adjust to slight variations like a human operator can.

Then came a digital mode called PSK31. It was a low-bandwidth slow digital protocol that used a computer’s soundcard to both send and receive. The computer could pull data out of what you would swear was nothing. There was some error correcting and other technical features that made PSK31 possibly better than Morse code for disadvantaged operations even by very skilled operators.

There are other similar digital modes, but most of them have not really caught on in the way that PSK31 has. Until FT8.

So FT8?

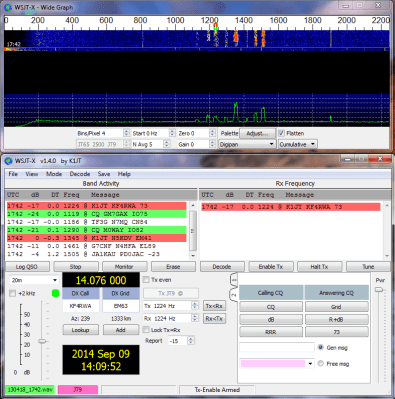

FT8 is a digital mode, too. It was specifically created to work well in really bad situations like meteor scatter or moonbounce. To maximize the chances of success, each FT8 packet holds 13 characters and takes 13 seconds to send. The protocol depends on a highly synchronized clock and every minute is divided into 15-second slots. Because of this FT8 contacts are highly structured and short. It’s like Twitter on sleeping pills. You won’t use FT8 to talk about your new motorcycle with your friend in Spain.

FT8 is a digital mode, too. It was specifically created to work well in really bad situations like meteor scatter or moonbounce. To maximize the chances of success, each FT8 packet holds 13 characters and takes 13 seconds to send. The protocol depends on a highly synchronized clock and every minute is divided into 15-second slots. Because of this FT8 contacts are highly structured and short. It’s like Twitter on sleeping pills. You won’t use FT8 to talk about your new motorcycle with your friend in Spain.

However, because the information is digital and of limited format, a typical exchange is that one operation calls CQ. Another operator notices and clicks on the first station in their display. Now their computers exchange basic information like location and signal strength. And then the contact is done.

The Good, The Bad…

If your goal is to “work” a lot of countries, or states, or islands, or any of the other entities hams try to get awards for, then this is great. It favors getting the minimum data through under the worst conditions. If you want to use ham radio to learn about other people and cultures, this doesn’t help because you just can’t say all that much. The truth is, though, that having long casual conversations with people very far away doesn’t happen as much as you’d think anyway.

[K5SDR’s] point, though, is that right now HF ham radio is on the brink of disaster even without FT8. The bands are bad and with antennas restricted, there isn’t much to do for a lot of hams. FT8 lets them get on the air. Purists complain it doesn’t take skill. But honestly, we’ve heard that before. Automated Morse code gear didn’t ruin ham radio. Nor did the availability of store-bought equipment.

Besides, this is all classic ham radio. There’s plenty of other things to do: emergency preparedness, radio control, propagation experimentation, and TV or image transmissions, just to name a few. If those don’t excite you, there’s moonbounce and satellites (even one orbiting the moon), so there’s always something to get involved with. The frontier is moving, and ham radio is moving with it, or at least maybe it should be.

Your Turn

What do you think? Is FT8 going to kill ham radio? Save it? If you aren’t a ham, does that make you think about getting your license? Or is it just another boring thing old guys do with their radios that you don’t care about? Let us know in the comments.

No comments:

Post a Comment