Love it or loathe it, the pharmaceutical industry is really good at protecting its intellectual property. Drug companies pour billions into discovering new drugs and bringing them to market, and they do whatever it takes to make sure they have exclusive positions to profit from their innovations for as long a possible. Patent applications are meticulously crafted to keep the competition at bay for as long as possible, which is why it often takes ages for cheaper generic versions of blockbuster medications to hit the market, to the chagrin of patients, insurers, and policymakers alike.

Drug companies now appear poised to benefit from the artificial intelligence revolution to solidify their patent positions even further. New computational methods are being employed to not only plan the synthesis of new drugs, but to also find alternative pathways to the same end product that might present a patent loophole. AI just might change the face of drug development in the near future, and not necessarily for the better.

Many Paths to Progress

In most industries, a patent is a simple concept: come up with a new idea, and if it proves to be novel, non-obvious, and useful, chances are good that a patent will be granted that prevents anyone but the owner from making, using, selling, or importing the covered invention for a certain period of time. The rub to the patent process is that the application must reveal everything about the invention publicly, which means that after the exclusivity period has expired, anyone can profit from the original inventor’s work.

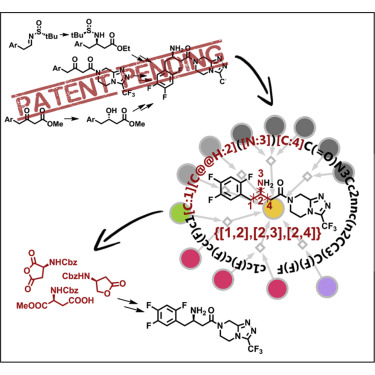

Pharmaceuticals, though, are treated differently. Since it’s relatively easy to reverse engineer a chemical compound using analytical chemistry tools and methods, patents for drugs concentrate on the process used to arrive at the desired endpoint. Most drugs are relatively simple organic compounds whose creation is a long, complicated series of reactions. They’ll often start with a couple of simple compounds, reacted together under just the right conditions to yield an intermediate compound. That product is then perhaps purified before being mixed with a fourth compound, and the process continues. Functional groups are added or subtracted at each step until the final compound is created in sufficient quantity and quality.

Every step in the process is claimed in the process patent application so that the resulting patent is as broad as possible. But it doesn’t stop there. There may be more than one way to skin the synthetic cat, and every single feasible alternative synthesis needs to be covered by the application too. Chemists at pharmaceutical companies spend a lot of effort looking for and plugging these potential patent loopholes.

AI to the Rescue

Both the design of the best, most commercially viable synthesis and the search for loopholes are perfect applications for AI. Syntheses can be broken down into well-defined steps governed by rules that an expert system can rapidly churn through, searching for a path from a known starting point to the desired product. Researchers at the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea had previously shown that an application called Chematica can autonomously generate a synthetic plan for a group of seven well-known drugs from simple starting materials. (Chematica was recently purchased by Merck and seems to have been rebranded as Synthia.) Each plan was generated in about 20 minutes and verified by chemists, who followed the synthetic instructions in the lab and came up with the right endpoints.

As a follow-up, the same team turned that process around, using Chematica to search for “retrosynthetic” paths to three new endpoints. This time, the products were blockbuster drugs with billions in sales and presumably air-tight patent positions. The researchers gave Chematica some rules, making certain key synthetic steps off-limits to the algorithm and forcing it to find alternate ways to the same product. To their surprise, paths to each of endpoints were discovered that successfully evaded the patent-infringing steps.

As a follow-up, the same team turned that process around, using Chematica to search for “retrosynthetic” paths to three new endpoints. This time, the products were blockbuster drugs with billions in sales and presumably air-tight patent positions. The researchers gave Chematica some rules, making certain key synthetic steps off-limits to the algorithm and forcing it to find alternate ways to the same product. To their surprise, paths to each of endpoints were discovered that successfully evaded the patent-infringing steps.

The implications of this development are potentially far-reaching. In the first instance, it seems like Chematica and similar tools will quickly become an aid to the intuitive, creative process of designing an organic synthesis. Such applications could also put a fair number of chemists out of a job, when it can do in 20 minutes what a chemist might take weeks or months to accomplish.

On the other hand, AI applications like these stand to stifle competition. The more airtight the patent position for a drug, the longer the patent owner can maintain a monopoly on that drug. Using AI to test for loopholes around the synthetic process only solidifies the claims, making it less likely that generic versions of a drug will reach the market in a timely fashion.

Taken at face value, the use of AI to both explore new routes to drug synthesis and find potential patent loopholes is a fascinating use of technology. But like anything else, the devil is in the details, and when such systems are inevitably put into widespread use, it’s likely that the ones that end up paying the price of progress will be the consumers.

No comments:

Post a Comment