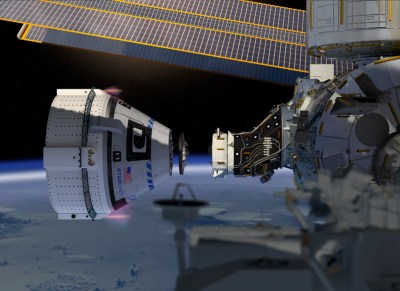

After a decade in development, the Boeing CST-100 “Starliner” lifted off from pad SLC-41 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station a little before dawn this morning on its first ever flight. Officially referred to as the Boeing Orbital Flight Test (Boe-OFT), this uncrewed mission was intended to verify the spacecraft’s ability to navigate in orbit and safely return to Earth. It was also planned to be a rehearsal of the autonomous rendezvous and docking procedures that will ultimately be used to deliver astronauts to the International Space Station; a capability NASA has lacked since the 2011 retirement of the Space Shuttle.

Unfortunately, some of those goals are now unobtainable. Due to a failure that occurred just 30 minutes into the flight, the CST-100 is now unable to reach the ISS. While the craft remains fully functional and in a stable orbit, Boeing and NASA have agreed that under the circumstances the planned eight day mission should be cut short. While there’s still some hope that the CST-100 will have the opportunity to demonstrate its orbital maneuverability during the now truncated flight, the primary focus has switched to the deorbit and landing procedures which have tentatively been moved up to the morning of December 22nd.

While official statements from all involved parties have remained predictably positive, the situation is a crushing blow to both Boeing and NASA. Just days after announcing that production of their troubled 737 MAX airliner would be suspended, the last thing that Boeing needed right now was another high-profile failure. For NASA, it’s yet another in a long line of setbacks that have made some question if private industry is really up to the task of ferrying humans to space. This isn’t the first time a CST-100 has faltered during a test, and back in August, a SpaceX Crew Dragon was obliterated while its advanced launch escape system was being evaluated.

We likely won’t have all the answers until the Starliner touches down at the White Sands Missile Range and Boeing engineers can get aboard, but ground controllers have already started piecing together an idea of what happened during those first critical moments of the flight. The big question now is, will NASA require Boeing to perform a second Orbital Flight Test before certifying the CST-100 to carry a human crew?

Let’s take a look at what happened during this morning’s launch.

A Matter of Time (and Fuel)

It’s important to understand that there was no catastrophic failure aboard the CST-100 this morning. The spacecraft and the United Launch Alliance Atlas V that carried it into space were operating normally during what has been described as a perfect launch. But upon separating from the booster rocket and continuing on its own independent flight, the CST-100 failed to achieve the necessary altitude to rendezvous with the ISS. While the craft is still fully functional, it simply doesn’t have enough propellant onboard to correct the situation.

Boeing currently believes the failure lies with the spacecraft’s Mission Event Timer (MET), an internal clock that starts running as soon as the spacecraft leaves the launch pad and is used to orchestrate automated systems during the mission. For reasons that are not yet known, the MET either failed or was not properly synchronized, which led to the engines not firing according on schedule. To make matters worse, the CST-100’s Reaction Control System (RCS) depleted the vehicle’s propellant reserves by attempting to make maneuvers that were unnecessary at the time.

Quite simply, the Starliner was confused about what tasks it was supposed to be performing after separation from the Atlas V booster. Normally, ground control would have been able to see the error and intervene, but as luck would have it, the event occurred during an expected communications blackout.

Once ground control reestablished communications with the vehicle and got it back on course, it became clear the planned rendezvous with the Station was out of the question. Both NASA and Boeing have been quick to point out that, had there been a human crew aboard this mission, they would likely have been able to switch over to manual control and resolve the issue on their own.

Because of this, there’s some debate as to how this situation will play out in terms of the CST-100’s certification for human flight. While issues with the autonomous systems obviously need to be addressed, astronauts are trained to handle precisely these sort of computer glitches. For better or for worse, there’s a long history of human crews having to take over when their vehicle’s systems have gone haywire.

In a post-launch interview, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine downplayed the issue, hinting that the failure doesn’t necessarily mean the CST-100 isn’t ready to start carrying human occupants:

What it really comes down to is automation. What we were trying to do is make sure we could do this entire mission end-to-end completely automated and that didn’t work. But here’s what’s important, the spacecraft is in orbit, the spacecraft is safe. If we would have had astronauts on board, they would have been safe. In fact, if we had astronauts on board, they probably would have taken over manually and would be flying to the International Space Station right now.

Critical Next Steps

While the Starliner won’t be able to demonstrate the critical rendezvous and docking maneuvers, the test is far from a complete loss. Being the first flight of a completely new spacecraft, the fact that the craft was able to reach orbit and maneuver on its own is itself a considerable success. Indeed, when SpaceX performed the first flight of their Dragon spacecraft in 2010, the vehicle only flew in space for a little over three hours before returning to Earth. The Dragon didn’t even attempt to reach the ISS until its second flight two years later. One could argue that the fact the CST-100 will remain in orbit for several days means that Boeing still outperformed rival SpaceX as far as inaugural missions go.

But that assumes the CST-100 touches down safely on Sunday. Should the vehicle fail to perform its deorbit burn, break up on reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere, or be unable to land safely, NASA will have no choice but to reevaluate the spacecraft’s flight readiness and further delay the Commercial Crew program. As it stands, if the next Starliner mission carries a human crew, it will do so with an untested ability to actually rendezvous and dock with the Space Station; a concerning reversal of the safety-first principles the agency has operated under since the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia.

No comments:

Post a Comment