Shell scripting is handy and with a shell like bash it is very capable, too. However, shell scripting isn’t always very efficient. Think about it. If you run grep or tr or sort to do some operation in a shell script, you are spawning a whole new process. That takes time and resources. But there are some answers to reducing — but not eliminating — the problem.

Have you ever written a program like this (in any language, but I’ll use C):

int foo(void)

{

...

bar();

}

You hope the compiler doesn’t write assembly code like this:

_foo:

....

call _bar

ret

Most optimizers should pick up on the fact that you can convert a call like this to a jump and let the ret statement in _bar return to foo’s caller. However, shell scripts are not that smart. If you have a shell script called MungeData and it calls another program or shell script called PostProcess on its last line, then you will have at one time three processes in play: your original shell, the shell running MungeData, and either the PostProcess program or a shell running the script. Not to mention, the processes to do things inside post process. So what do you do?

Enter Exec

There are a few possible answers to this, but in the particular case where one shell script calls another program or script at the end, the answer is easy. Use exec:

#!/bin/bash # Do stuff here ... # Almost done exec PostProcess

This tells the shell to reuse the current process for PostProcess. Nothing that appears after the exec will run because the current process is wiped out. When PostProcess completes, the original process that called our script will resume. This is pretty much the same as the call/ret to jump optimization in C.

Built Ins

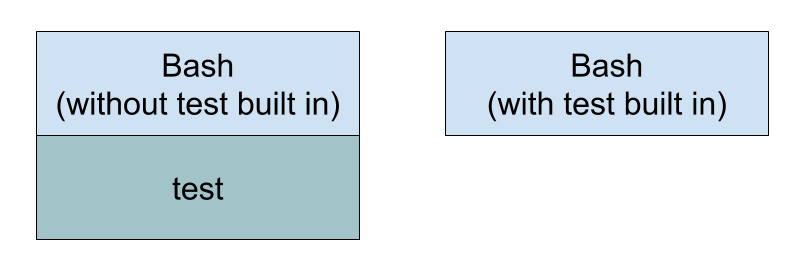

If you look at the bash manual, some things are built in and some are not. Using built ins ought to be faster than spawning a new program. For example, consider a line like:

if [ $a == $b ]

Some shells use a program named “test” to handle the square brackets. This causes a new program to launch. Modern bash provides this as a built in to help speed script execution and make it more efficient. However, you can disable it if you want to benchmark the difference. In general, you can disable a built in using “enable -n XXX” where XXX is the built in you want to disable. Use no options to enable it. Just entering the command with no arguments at all will give you a list of built in commands or use the -p option, if you prefer.

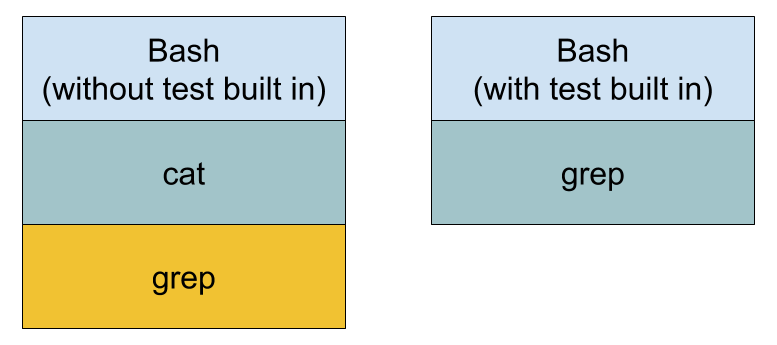

However, there’s more to it than that. If you have some common operation that takes a lot of overhead, you can write the code in a language such as C and ask the shell to load it as a shared object and then treat it as a built in. The technique is a little involved, but it shows the versatility of the shell. You can find an example that adds a few built in commands to bash in this article. For example, the code posted makes things like

However, there’s more to it than that. If you have some common operation that takes a lot of overhead, you can write the code in a language such as C and ask the shell to load it as a shared object and then treat it as a built in. The technique is a little involved, but it shows the versatility of the shell. You can find an example that adds a few built in commands to bash in this article. For example, the code posted makes things like cat and tee part of the shell, as well as creating new commands.

Exotic Solutions

We’ll admit, that last solution is a bit exotic. However, there are other things you can do. You might create a persistent server and communicate with it using a named pipe to avoid running new code. When disks were slow, you could experiment with keeping frequently used programs on a RAM disk. Today, caching ought to do that almost automatically, but perhaps not in every scenario.

Sometimes just cleaning up your code can help. Imagine this:

cat "$1" | grep "$target"

This spawns two processes, one for cat and one for grep. Why not just say:

grep "$target" "$1"

Of course, the ultimate is to simply not use a shell script. Almost any programming language will have a richer set of things it can do without launching an external program. A compiled or semi-compiled language is likely to be faster and even will help you optimize.

Shell scripts are useful to a point. It is fun, too, to see just how far you can stretch them. However, if you are really that worried about efficiency or speed, this might be the best answer of all.

No comments:

Post a Comment