In the 1950s, American automobiles bloomed into curvaceous gas-guzzlers that congested the roads. The profiles coming out of Detroit began to deflate in the 1960s, but many bloat boats were still sailing the streets. For all their hulking mass, these cars really weren’t all that stable — they still had issues with sliding and skidding.

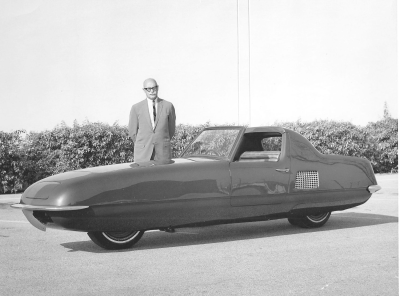

One man sought to fix all of this by re-imagining the automobile as a sleek torpedo that would scream down the road and fly around turns. This man, Alex Tremulis, envisioned the future of the automobile as a two-wheeled, streamlined machine, stabilized by a gyroscope. He called it the Gyro-X.

A Revolutionary Two-Wheeler

Alex Tremulis had designed many cars that were futuristic for their time, like the Cord 810/812 and the Tucker ’48. He went to work for Ford in 1952 as the Chief of Advanced Styling, and helped design the Ford Gyron concept car in 1961.

When you consider that gyros have long been used to stabilize everything from space ships to submarines, a gyroscopic car is really not that far-fetched. Try as he might, Tremulis couldn’t get Ford to seriously invest in the idea. A few years after the Gyron, Tremulis designed the Gyronaut X-1, a streamlined motorcycle that set a few land speed records at Bonneville.

Tremulis left Ford and teamed up with gyroscope expert Thomas Summers, who usually dealt with missiles and rockets. In 1963, Tremulis and Summers founded Gyro Transport Systems in Northridge, CA. The two secured $750,000 from investors — that’s roughly $6.3 million in today’s money — to create what was supposed to be the future of the automobile: sleek but safe, small but stylish.

Lean, Mean Driving Machine

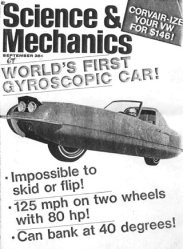

The prototype was up and running by 1967, and appeared at the International Automobile show in New York. The magazine Science & Mechanics featured it in their September 1967 issue.

The Gyro-X proves that it’s possible to design an economy car without sacrificing a shred of speed or style. It could do 120 MPH with only an 80-horsepower Mini Cooper engine mounted in the back. It turned like a motorcycle, but with no leaning necessary — just turn the wheel and the gyro leans the car for you. When it was time to park, outrigger training wheels dropped down to keep it from falling over.

At just 42″ wide, two cars could fit side by side in the same lane, as dangerous as that sounds. Just before the company went under, Tremulis was working on a family version that was a whole foot wider and three feet longer — a real grocery-getter.

Of course, the real feature is the gyroscope that made this tiny two-wheeler possible in the first place. The 22″ diameter gyro sat in front, mere inches from the driver’s kneecaps.

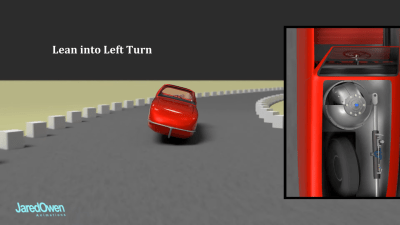

When the car is driving in a straight line, the gyro makes micro adjustments to keep it upright. As the steering wheel is turned in either direction, the gyro moves in unison with the front wheel.

The gyroscope was hydraulically driven off the motor, and it took three full minutes to wind its way up to 6,000 RPM, so it’s not intended for quick getaways. But the gyro would keep spinning for about two hours after the car shut off. Perhaps that energy could have been used to charge a generator for an electric motor, or a battery for charging electronic devices.

Spinning Out of Control

Though the Gyro-X could do 120 MPH, it probably shouldn’t have. The two-wheeled wonder was consistently unstable at speeds over 70 MPH. Tremulis and Summers couldn’t solve the complicated engineering issues quickly enough to please the investors, who got antsy and pulled their money. By 1970, Gyro Transport Systems was out of business.

The Road to Restoration

The only Gyro-X ever produced became the custody of Thomas Summers. By 1975, he had turned it into a three-wheeler and put a Volkswagen engine in the back so he could license it in California.

It disappeared for a while and resurfaced in 1994, when a Las Vegas musician named John Windsor obtained it as payment for a debt. The car was nearly unrecognizable, and the gyro itself was long gone.

Windsor put up a video in 2009 giving a tour of the car and explaining how he came to own it. He didn’t know what he had, and so he used the internet to spread the word. It worked. The video got a bite, and Windsor sold it to a private collector, who may have bitten off more than they could chew.

In 2011, Jeff Lane, founder and director of the Lane Motor Museum in Nashville, Tennessee bought it from the collector and started pushing the Gyro-X down the road to restoration. Lane and his crew painstakingly restored it from photos and a few known measurements, an effort that took several years and around half a million dollars. The hardest part was, of course, replacing the gyro. You can’t just find those things, not at that scale. Lane hired an Italian firm specializing in yacht-stabilizing technology to make a new gyro, and that required them to fly someone out to do digital scans of the car.

Here is a brief documentary about the restoration effort, which was filmed somewhere in the middle of the process. Below are images of the fully-restored Gyro-X, all courtesy of the Lane Motor Museum. After that, we’ve embedded some vintage footage of it whizzing around Southern California.

Thanks to [Jared Owen] and his fantastic animation channel for inspiring this post.

Retrotechtacular is a weekly column featuring hacks, technology, and kitsch from ages of yore. Help keep it fresh by sending in your ideas for future installments.

No comments:

Post a Comment