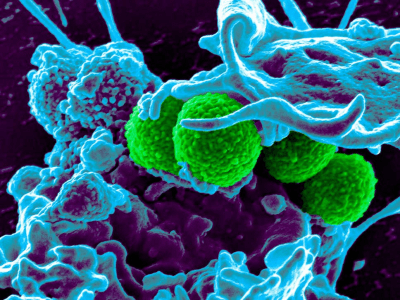

Researchers at McMaster University in Ontario have developed a plastic wrap that repels viruses and bacteria, including some of the scariest antibiotic-resistant superbugs known to science. With the help of a scanning electron microscope, the researchers were able to watch superbugs like MRSA and Pseudomonas bounce right off the surface.

The wrap can be applied to things temporarily, much like that stuff you wrestle from the box and stretch over your leftovers. It can also be shrink-wrapped to any compatible surface without losing effectiveness. The ability to cover surfaces with bacteria-shielding armor could have an incredible impact on superbug populations inside hospitals. It could be shrink-wrapped to all kinds of things, from door handles to railings to waiting room chair armrests to the pens that everyone uses to sign off on receiving care.

According to the CDC, there are more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections reported in the United States each year, resulting in over 35,000 deaths. These superbugs are most prevalent and dangerous in hospitals and other medical settings like nursing homes, and they’re especially threatening to the weakened immune systems of chemo patients, dialysis patients and anyone undergoing surgery.

The superbug crisis pivots on the point that antibiotics are a double-edged sword. As they fight infection, they also weaken immune systems, which allows antibiotic-resistant bugs to proliferate in easily-won battlegrounds. Doctors have little choice but to use more toxic and potentially ineffective types of antibiotics to treat antibiotic-resistant infections. On top of everything else, these drugs are often more expensive.

One of the first lines of defense for avoiding large-scale superbug threats in the first place is protecting the food supply. This fantastic plastic could really beef up sanitation practices at food-packaging plants where salmonella and E. coli lurk.

The Lotus Effect

The key to this antibacterial trampoline is in the surface topography. It’s made of of microscopic wrinkles meant to mimic the lotus effect — that repellent property of lotus leaves that makes water bead on their surface.

Lotus leaves are covered with tiny pointed bumps that disrupt the surface so much that water is unable to settle and spread out. The tips of these bumps are coated in a wax secreted by the plant that furthers its hydrophobic properties. They are often described as self-cleaning, because the beaded water droplets carry dirt particles away with them.

The researchers say they also treated their plastic wrap chemically “to further enhance its repellent properties”, though it’s unclear what chemical they’re talking about. Hopefully, it’s something innocuous that acts like wax.

Where Did All the Brass Door Knobs Go?

Our more experienced readers might recall that we already have a kind of antibacterial door knob technology, and it’s been around for quite a long time.

Copper, brass, and silver all exhibit the oligodynamic effect, which means they are slowly poisonous to bacteria. Many door knobs and public surfaces used to be made of brass to take advantage of the biocidal effect. This would only go so far in the hospital setting, because the effect takes several hours.

So why aren’t all door knobs still made of brass? Who can really say? Tastes change, brass tarnishes, and people forget about the oligodynamic effect. C’est la vie.

Resistance May Be Futile

At first blush, this special wrap sounds like something we’d want to put absolutely everywhere, like all public surfaces and our phones. MRSA and other antibiotic-resistant superbugs don’t exist solely within hospital walls, after all. But not all forms of bacteria are bad — in fact, plenty of good bacteria called gut flora lives in our intestines. It’s an important part of our immune system that keeps us from getting sick every single time we encounter a new pathogen. If every public surface was covered in this stuff, we couldn’t pick up germs nearly as well because they wouldn’t stick anywhere.

From a practical standpoint, this stuff is only going to be useful if that special surface can stand up to the wear and tear of hospital environments without being crushed or worn away. It would also have to survive the frequent, rigorous, and probably bleach-based cleaning routines. One little scratch or ding in the armor, and you have a disgusting little critter crevice crawling with superbugs.

Let’s say this stuff is everywhere ten or fifteen years from now. Is there a downside to repelling so much bacteria? Where will it all go? Will it gang up? Would it mean an increase in airborne bacteria? And what about that secret sauce chemical they treated the plastic wrap with to make it more repellent? Will we regret exposing ourselves to it?

That said, the researchers don’t intend for this stuff to be the answer to the superbug problem, just a weapon in the arsenal. It seems to us to be worth a shot to use it in medical facilities, but of course, time will tell.

Main image via CTV News

No comments:

Post a Comment