The field of computer science has undeniably changed the world for virtually every single person by now. Certainly for you as Hackaday reader, but also for everyone around you, whether they’re working in the field themselves, or are simply enjoying the fruits of convenience it bears. What was once a highly specialized niche field for a few chosen people has since grown into a discipline that not only created one of the biggest industry in modern times, but also revolutionized every other industry, some a few times over.

The fascinating part about all this is the relatively short time span it took to get here, and with that the privilege to live in an era where some of the pioneers and innovators, the proverbial giants whose shoulders every one of us is standing on, are still among us. Sadly, one of them, [Tony Brooker], a pioneer of the early programming language concept known as Autocode, passed away in November. Reaching the remarkable age of 94, the truly sad part however is that this might be the first time you hear his name, and there’s a fair chance you never heard of Autocode either.

But Autocode was probably the first high-level computer language, and as such played a fundamental role in the development of whatever you’re coding in today. So to honor the memory of [Tony Brooker], let’s remember the work he did with Autocode, and the leap in computer science history that it represented.

The Early Days

When it comes to ancient programming languages, Fortran and COBOL are always prime candidates to mention. Created in the late 1950s, these languages are surrounded by an almost mythical vibe. Developers much younger than the languages themselves, who have never saw a line of COBOL in the wild, will tell each other equally mythical stories about a distant relative who was once working with it in a laboratory or some other too-good-to-be-true environment.

Not that age really matters here; assembly is even older, and it is highly unlikely that it will ever lose its relevance. However, the difference is that assembly is a low-level language, while most other languages out there, including Fortran and COBOL, are high-level languages. Programming in assembly means writing in whatever instruction set a processor provides. Assembly languages are just handy mnemonics for the raw bits that the machine speaks. High-level languages on the other hand care a lot less about a processor’s instruction set, and are abstracting those details away to resonate more with the dynamics of the human mind instead.

Take a simple multiplication as example: in a typical high-level language, you’d simply write a = b * c, while in assembly, you’d write whatever the target processor itself knows about multiplication. You might load the multiplicands into dedicated registers and the CPU might have a multiplication instruction, or it might need to loop through a series of additions. You have to know how the chip works. In a high-level language, it’s going to be a compiler’s task to figure out how to do the actual multiplication and create the corresponding assembly code for it.

The Missing Link

So how does Autocode fit into all this, and what is it anyway? It was designed after assembly was invented, but before any high-level language has existed. Assembly itself was a rather hot new topic at this point in time, when people were still carving their bits by hand. Well, obviously not literally, but “programming” the computers of that time was tedious, non-intuitive, and error-prone work. Except for an early version of a compiler-like construct named Autocode, developed by [Alick Glennie].

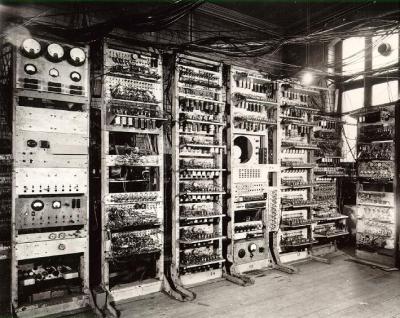

One computer of the early days was the Manchester Mark 1, the direct successor of the Baby, and the machine [Alan Turing] was working with in the computer lab at Manchester University. It supposedly had a rather nasty instruction set that made the tedious nature of machine-language programming even worse, which was the first motivation to create Autocode: taming the machine.

[Glennie]’s version of Autocode was a nice-syntax wrapper that remained otherwise machine-dependent, and we’d have to classify it as a low-level language. It wasn’t until the hero of our story, [Tony Brooker], came along to take a second shot at the idea of Autocode, that the first high-level language was written.

Legend says, one day, while on the way back to Cambridge where he was working as computer researcher, he popped into the Manchester University computer lab, introducing himself and his work to [Alan Turing]. Mutual interest in their work ensured, and [Tony Brooker] joined the computer lab to create his life’s work as part of his task to make the Mark 1 easier usable: designing an intuitive language with human-readable syntax that would hide away all the low-level nastiness, a language that wouldn’t require wasting countless hours of learning and deciphering each and every bit of the hardware, and ultimately turns the underlying hardware more or less into an irrelevant detail the programmer shouldn’t worry too much about. In short, it was planned as a true high-level language.

Starting development in 1954, the Mark 1 Autocode was ready the year after, and apart from the hardware independence, it also supported floating point arithmetic. While it had a few limitations with naming conventions and syntax, it was a big success in Manchester. [Tony Brooker] went on to continue developing the Autocode concept not only to other machines, but to the very concept of language creation itself. Taking Autocode further and further, he created the very first compiler-compiler in 1960, becoming virtually unstoppable with developing new languages.

Something To Build Upon

In a time where assembly was practically the epitome of convenience to operate a computer, the concepts of [Tony Brooker]’s version of Autocode took programming to the next level, and paved the way for a whole new realm of languages to come. And there was no one single Autocode language, just as there is no single, one assembly language. Autocode will probably be best thought of as a principle that has since evolved into the domain of compiled, high-level languages.

Unlike COBOL or Fortran, nobody codes in Autocode anymore. It’s a nearly forgotten relic of the past, regardless of the role it once played in the history of computer science. But the ideas that were embodied in Autocode live on. Without doubt, the creation of high-level programming languages was inevitable, yet it’s hard to fully appreciate today the work it took for pioneers like [Tony Brooker] to actually take the first steps towards it all those decades ago. Worth remembering.

No comments:

Post a Comment