In whichever hemisphere you dwell, winter is the time of year when viruses come into their own. Cold weather forces people indoors, crowding them together in buildings and creating a perfect breeding ground for all sorts of viruses. Everything from the common cold to influenza spread quickly during the cold months, spreading misery and debilitation far and wide.

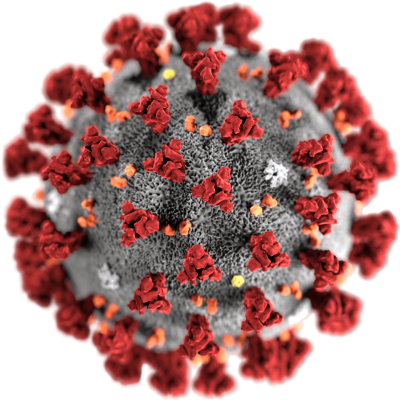

In addition to the usual cocktail of bugs making their annual appearance, this year a new virus appeared. Novel coronavirus 2019, or 2019-nCoV, cropped up first in the city of Wuhan in east-central China. From a family of viruses known to cause everything from the common cold to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in humans, 2019-nCoV tends toward the more virulent side of the spectrum, causing 600 deaths out of 28,000 infections reported so far, according to official numbers at the time of this writing.

(For scale: the influenzas hit tens of millions of people, resulting in around four million severe illnesses and 500,000 deaths per season, worldwide.)

With China’s unique position in the global economy, 2019-nCoV has the potential to seriously disrupt manufacturing. It may seem crass to worry about something as trivial as this when people are suffering, and of course our hearts go out to the people who are directly affected by this virus and its aftermath. But just like businesses have plans for contingencies such as this, so too should the hacking community know what impact something like 2019-nCoV will have on supply chains that we’ve come to depend on.

Unhappy New Year

The 2019-nCoV outbreak could not have come at a worse time in China’s calendar. Although there is some dispute about whether the virus really first appeared at the end of December or if it cropped up earlier in the month, it’s the fact that it bumped into the annual Chinese lunar new year holiday that counts. And the cultural elements surrounding this time of year are key to understanding what effect the outbreak will have on supply chains, and the degree to which the hacker community will be impacted.

The Chinese New Year starts on the day of the new moon that occurs between January 21 and February 20; this year the holiday began on January 25. It kicks off the Spring Festival, with most people getting a full week off from work to visit relatives and celebrate. The resulting travel period dwarfs every other periodic human migration, with up to 385,000,000 people on the move, mostly on the country’s extensive rail system. The travel season generally starts two weeks before the lunar new year and lasts for about 40 days.

The Chinese New Year starts on the day of the new moon that occurs between January 21 and February 20; this year the holiday began on January 25. It kicks off the Spring Festival, with most people getting a full week off from work to visit relatives and celebrate. The resulting travel period dwarfs every other periodic human migration, with up to 385,000,000 people on the move, mostly on the country’s extensive rail system. The travel season generally starts two weeks before the lunar new year and lasts for about 40 days.

Since much of the Chinese labor force is made up of workers who come from rural areas to large cities where jobs are more readily available, the annual New Year migration is mostly in the opposite direction – from the cities to the countryside. Aside from travel headaches, the lunar new year holiday doesn’t cause much disruption in a normal year because everyone has more or less the same time off from work. Factories traditionally shut down for the week, markets like those in Shenzhen board up, and business returns to normal after everyone returns to work well-fed and rested. This year, though, is anything but normal.

In response to the increasing death toll of the novel virus, Chinese officials imposed a de facto quarantine on Wuhan, the city at its epicenter, by cutting all rail and air service to the city of 11 million on January 23. Other cities followed with equally draconian lockdowns until eventually more than 50 million people were isolated. The lunar new year festivities were officially extended by three days, and things were supposed to get back to normal work-wise by February 3, but many factories are still shut down. This is partly due to the continuing increase in new cases of the infection, but also due to travel restrictions keeping workers who made it out of the cities before the quarantine from returning.

Your Turn

With businesses understaffed, there’s a good chance that the normal Chinese New Year supply chain disruptions will not only continue well past the end of the holiday, but possibly worsen. The financial news is filled with stories of potential disaster for manufacturers like Apple, who have outstanding orders for 45 million AirPods with Chinese contract manufacturers. Similar tales of financial woe abound for every industry whose supply chain passes through China, from automobiles to pharmaceuticals.

But what impact will any of this have on us? The hacking community’s slice of the global market from electronics may be small compared to the needs of an Apple or a Foxconn, but we source a lot of stuff from the currently shuttered markets of Shenzhen. Lots of those modules and boards we so love to include in our projects come from China. What happens if nobody shows up to work, either by necessity or by choice, to fulfill those orders?

With all that in mind, we’d like to turn the question over to the readers. Have you noticed any problems getting parts and supplies from China since the start of the coronavirus outbreak? Any delays in fulfilling or shipping orders? Have any suppliers contacted you to warn you of possible disruptions? What about those of you who place larger orders, perhaps as part of your jobs? Are your companies giving you any guidance on supply chain disruptions? We’d also love to hear from our friends in China, both to wish them well and for a boots-on-the-ground report. Please sound off in the comments below, with all due respect and sensitivity for the seriousness of the situation.

No comments:

Post a Comment