One of the strangest things about human nature is our tendency toward inertia. We take so much uncontrollable change in stride, but when our man-made constructs stop making sense, we’re suddenly stuck in our ways — for instance, the way we measure things in the US, or define daytime throughout the year. Inertia seems to be the only explanation for continuing to do things the old way, even when new and scientifically superior ways come along. But this isn’t about the metric system — it’s about something much more personal. If you use a keyboard with any degree of regularity, this affects you physically.

Many, many people are content to live their entire lives typing on QWERTY keyboards. They never give a thought to the unfortunate layout choices of common letters, nor do they pick up even a whisper of the heated debates about the effectiveness of QWERTY vs. other layouts. We would bet that most of our readers have at least heard of the Dvorak layout, and assume that a decent percentage of you have converted to it.

Hardly anyone in the history of typewriting has cared so much about subverting QWERTY as August Dvorak. Once he began to study the the QWERTY layout and all its associated problems, he devoted the rest of his life to the plight of the typist. Although the Dvorak keyboard layout never gained widespread adoption, plenty of people swear by it, and it continues to inspire more finger-friendly layouts to this day.

Composer of Comfort

August Dvorak was born May 5th, 1894 in Glencoe, Minnesota. He served in the US Navy as a submarine skipper in WWII, and is believed to be a distant cousin of the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák. Not much has been published about his early life, but Dvorak wound up working as an educational psychologist and professor of the University of Washington in Seattle, and this is where his story really begins.

Dvorak’s interest in keyboards and typing was struck when he advised a student named Gertrude Ford with her master’s thesis on the subject of typing errors. Touch typing was only a few decades old at this point, but the QWERTY layout had already taken a firm hold on the industry.

As Dvorak studied Ford’s thesis, he began to believe that the QWERTY layout was to blame for most typing errors, and was inspired to lead a tireless crusade to supplant it with a layout that served the typist and not the typewriter. His brother-in-law and fellow college professor, William Dealey, joined him on this quest from the beginning.

AOEUIDHTNS

Dvorak and Dealey put a great deal of effort into analyzing every aspect of typing, studying everything from frequently-used letter combinations of English to human hand physiology. In 1914, Dealey saw a demonstration given by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, who were using slow-motion film techniques to study industrial processes and worker fatigue. He told Dvorak what he’d seen, and they adopted a similar method to study the minute and complex movements of typists.

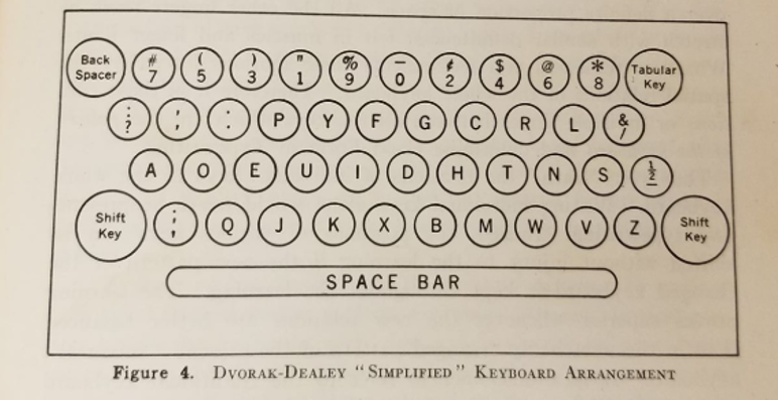

In 1936, after two decades of work, Dvorak and Dealey debuted a new layout designed to overcome all of QWERTY’s debilitating detriments. Whereas QWERTY places heavy use on the left hand and forces fingers outside the home row over 60% of the time, the Dvorak layout favors hand alternation and keeping the fingers working at home as much as possible. In this new arrangement, the number of words that can be typed without leaving the home row increased by a few thousandfold. Dvorak and Dealey along with Gertrude Ford and Nellie Merrick published all of their psychological and physiological findings about typing in the now out-of-print Typewriting Behavior (1936).

Haters Gonna Hate

At first, it seemed as though the Dvorak-Dealey simplified layout had half a chance of supplanting QWERTY. Dvorak found that students who had never learned to touch type could pick up Dvorak in one-third the time it took to learn QWERTY.

Dvorak entered his typists into contests, and they consistently out-typed the QWERTYists by a long shot. It got so bad that within a few years, Dvorak typists were banned outright from competing. This decision was overturned not long after, but the resentment remained. QWERTY typists were so unnerved by the speed of the Dvorak typists that Dvorak typewriters were sabotaged, and he had to hire security guards to protect them.

The QWERTY is Too Strong

Although there were likely many factors at play, the simple fact is that by the time Dvorak patented his layout, Remington & Sons had cornered the market on typewriters. Even so, Dvorak released his keyboard during the Depression, and hardly anyone could afford to buy a new typewriter just because there was some hot new layout.

Although Dvorak typewriters were never mass-produced, they almost made waves thanks to the US Navy. Faced with a shortage of trained typists during WWII, they experimented with retraining QWERTY typists on Dvorak and found a significant increase in speed. They allegedly ordered thousands of Dvorak typewriters, but were vetoed by the Treasury department because of QWERTY inertia.

August Dvorak went on to make one-handed keyboards with layouts for both the left and right hand. In 1975, he died a bitter man, never understanding why the public would continue to shrug their overworked shoulders and keep using QWERTY keyboards. He might have been pleased to know that the Dvorak layout eventually became an ANSI standard and comes installed on most systems, but dismayed to find the general population still considers it a fringe layout.

I’m tired of trying to do something worthwhile for the human race. They simply don’t want to change!

No comments:

Post a Comment