Long ago, before smartphones were ubiquitous and children in restaurants were quieted with awful games on iPads, there was a beautiful moment. A moment in which the end user could purchase, at a bargain price, an x86 computer in a compact, portable shell. In 2007, the netbook was born, and took the world by storm – only to suddenly vanish a few years later. What exactly was it that made netbooks so great, and where did they go?

A Beautiful Combination

The first machine to kick off the craze was the Asus EEE PC 701, inspired by the One Laptop Per Child project. Packing a 700Mhz Celeron processor, a small 7″ LCD screen, and a 4 GB SSD, it was available with Linux or Windows XP installed from the factory. With this model, Asus seemed to find a market that Toshiba never quite hit with their Libretto machines a decade earlier. The advent of the wireless network and an ever-more exciting Internet suddenly made a tiny, toteable laptop attractive, whereas previously it would have just been a painful machine to do work on. The name “netbook” was no accident, highlighting the popular use case — a lightweight, portable machine that’s perfect for web browsing and casual tasks.

But the netbook was more than the sum of its parts. Battery life was in excess of 3 hours, and the CPU was a full-fat x86 processor. This wasn’t a machine that required users to run special cut-down software or compromise on usage. Anything you could run on an average, low-spec PC, you could run on this, too. USB and VGA out were available, along with WiFi, so presentations were easy and getting files on and off was a cinch. It bears remembering, too, that back in the Windows XP days, it was easy to share files across a network without clicking through 7 different permissions tabs and typing in your password 19 times.

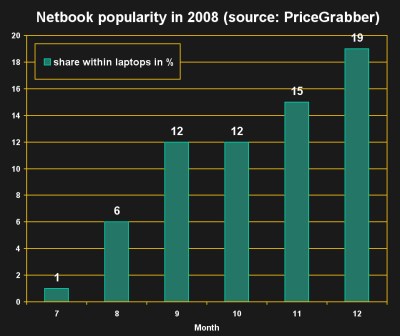

The netbook was the perfect machine for the moment. It took full advantage of modern hardware advances, and created a highly usable machine for the important job of surfing the web all day, chatting to your friends. Later models began to push the envelope, with screens pushing out to 9 and later 10 inches, packing more storage, and even featuring battery lives up to 6 hours. Back in 2008, these were crazy numbers, and having less than 20GB of storage wasn’t a liability like it is today. Finally, there was the price. Low-tier models could be had for under $300. The buying public loved it, and sales shot through the roof. In July 2008, netbooks made up just 1% of total laptop sales. By December, they had almost a fifth of the market.

However, netbooks quickly became a victim of their own success. Hardware manufacturers didn’t appreciate them cutting into sales of higher-end models which came with larger profit margins. Microsoft and Intel began to put pressure on manufacturers to limit specifications. Windows 7 licencing costs were jacked up for any machine with a screen size over 10.1 inches, killing off a series of larger netbooks that had edged towards 12″ screens. Microsoft also floated the idea of a cut-back Windows 7 Starter edition, limited to running just 3 programs at a time. At the same time, as manufacturers sought to compete on features, prices for higher-end models began to rise, outside of the original cheap-and-cheerful brief the netbook originally had.

In the end, the real death knell for the netbook came in the form of the iPad. For the vast majority of users, what they wanted was a simple, cheap internet machine to run Facebook and browse the web. As tablet sales grew, netbook sales fell off a cliff. Trapped between a new competitor and vendors keen to block them out of the market, the netbooks quickly disappeared. In their place, subnotebooks and ultrabooks stormed in – with much larger models at over three times the price point. By 2012, the netbook was effectively dead.

Irreplaceable For The Power User

While the average user found themselves better served by a basic tablet than a tiny laptop, it’s the power users that lost the most when the netbook was killed. There’s great charm and utility in a laptop that can be easily carried with one hand without risk of being dropped or tipping over. Despite the diminutive size, many netbooks packed competent keyboards; I was easily hitting 100 words per minute on an early EEE PC 901. Combined with multiple USB ports and a full Windows install, it made an excellent portable development machine.

A netbook could be carried around in the field, and interface with all manner of hardware. Being a full-fat x86 computer, it ran IDEs, programmed Arduinos, and connected to the Web, all in one neat package. Precisely none of these things can be achieved as easily with a tablet. There are plenty of Bluetooth keyboards and adapter dongles and special apps for working with hardware, but tablets simply can’t compete with a real computer for doing real work. For a hardware hacker on the go, it was a glorious tool. And, at such a low price, it was accessible to everyone — even a broke university student.

Thankfully, hope is on the horizon. The hardware market is a different place in 2020, and the netbook concept has once again shown viability to manufacturers. To qualify as a true netbook, a machine must hold true to the original values that made them great. Machines running a mobile OS, ARM processor (although that may change in the near future as OSes continue to ramp up support), or have other software limitations are not worthy to wear the name. Compact size and low price are also key attributes.

Models like the HP Stream and ASUS VivoBook pick up where netbooks left off. Packing just 4GB of RAM and low-end CPUs, they’re not powerful machines – but they’re not supposed to be. They’re a real computer for under $300 USD, shipping with Windows 10 S. This is an “app store” version of Windows, but can be upgraded to full WIndows 10 at no cost. With under 100GB of storage, you won’t want to load these down with all your photos, videos, and applications. But, with many of us leaving all that in the cloud anyway, it won’t hold you back.

The main competitor holding back the netbook from true glory is no longer the tablet, but the Chromebook. Running a special Linux-based OS crafted by Google, these machines are intended to be lightweight web browsers, and little more. Rather than running local apps, they’re designed to work almost solely in the cloud, with a browser-based app framework. The platform has become widely popular at the bottom end of the laptop market, crowding out the possibilities of a full netbook resurgence. They do, of course, have a hardcore Linux following that happily scrap ChromeOS for a Linux install or run them side-by-side with a healthy dose of workarounds to suit the hardware. This is where a lot of the netbook aficionados ended up when the netbook hardware standard became scarce.

An Eye To The Future

It’s unlikely that we’ll see netbooks return to the prominence they once held for those four amazing years at the turn of the last decade. The average user looking for a social media machine is best served by tablets or cut-down Chromebooks. This leaves powerusers as the primary market for the netbook, and many with larger pocketbooks will simply opt for a more powerful ultrabook instead. Pour one out for the college students, who will have to mortgage their beat-up Corolla, or else lug a bulky 15″ clunker over to their capstone project to figure out how they let the smoke out. For now, netbooks remain sleeping — may they one day rise again.

No comments:

Post a Comment