We’re now several months into the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with most parts of the world falling somewhere on the lockdown/social distancing/opening up path.

It’s fair to say now that while the medical emergency has not passed, the level of knowledge about it has changed significantly. When communities were fighting to slow the initial spead, the focus was on solving the problem of medical protection gear and other equipment shortages at all costs with some interesting yet possibly hazardous solutions. Now the focus has moved towards protecting the general public when they do need to venture out, and as society learns to get life moving again with safety measures in place.

So, we all need masks of some sort. What type to do you need? Is one type better than another? And how do we all get them when everyone suddenly needs what was once a somewhat niche item?

Masks Offer Basic Protection for Everyone in Public Areas

Some parts of the world are coming to terms with the effects of long term lockdown, while others are beginning to contemplate how they might start moving back towards some kind of normality. The issue of mask wearing a practical one, because there are indications that it will slow the spread of the disease.

When considering face masks, it’s important to start by defining what a mask for the general public should be, and what it is trying to achieve. This is not the same breed as the masks worn by intensive care staff where the primary intention is to protect the wearer by filtering the virus from an atmosphere heavily contaminated with it, instead it is a mask intended to be worn in environments where only a few people may be spreading the virus (with the pesky detail of not knowing who those few people are).

The goal of masks is to reduce the chances of transmission by infected droplets. It’s an idea wittily illustrated in the “Urine Test” meme, that such a mask will not guarantee your escape from the virus but it should significantly reduce the odds of its transmission. We’re told that these odds tilt further against the virus the more people in an environment wear a mask, and since it’s a relatively easy step to take it’s one that everyone should be taking as a courtesy to your fellow humans.

We’re Makers, Yes… But You Can Learn a Lot From Commercial Masks

In our community the first thought turns invariably towards making our own and indeed that’s part of the official advice in many territories, but before we go there it’s worth considering the commercial alternatives. These normally use a composite design featuring multiple layers of fabric for comfort and filtration, with the main filter layer(s) being of a blown fabric rather than a woven one.

If you have a supply of the top-spec medical masks then you’re all set, but since pandemic demand has caused a supply shortage that’s a luxury most of us can’t claim and shouldn’t be taking from the professionals who need them anyway. We will often have an array of other masks to hand as dust protection in the workshop, and among these can be found some surprisingly good protection for our application. The key is in the rating which should be printed on the box or the outside of the mask, but to decode what it means will sometimes require a bit of digging into the world of international standards.

Assuming that you didn’t buy from the cheapest seller on AliExpress and your mask isn’t counterfeit, you may encounter US standards (N95 etc), EU standards (EN149, FFP etc.), or Chinese standards (T3210-2016 etc.). These deal among other properties with the mask’s particulate filtration ability both in terms of particle size and percentage removal, and with the breathing force required to make air pass through them. Happily our requirement for a droplet-catcher does not require the most stringent of standards. As an aside, the official versions of all the above mentioned standards seem all to be behind very expensive paywalls. It’s not difficult to find them online through your search engine though.

Tearing Down Some Masks

So casting around the commercial masks we have to hand here brings out a pair of dust masks and a surgical style mask that admirably illustrate the range on offer. An FFP3 dust mask is a European-rated rough equivalent of those N95 surgical masks in industrial form, and it feels thick between finger and thumb. Despite having probably the best available filtration, our FFP3 is not suitable as virus protection because it manages exhalation through a non-return valve that would release droplets into the atmosphere.

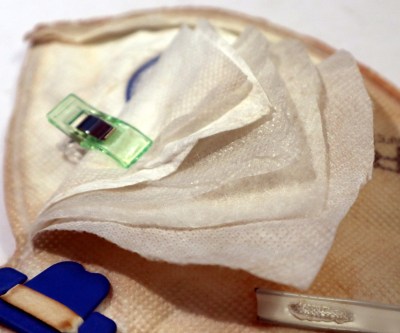

Taking the used FFP3 mask from my overall pocket that has protected me from dust during several woodwork machining sessions at MK Makerspace and cutting it open, it is revealed as having five non-woven layers including a thick and fluffy one and a very dense one. When compressed with a micrometer screw gauge its thickness is a relatively substantial 0.94mm.

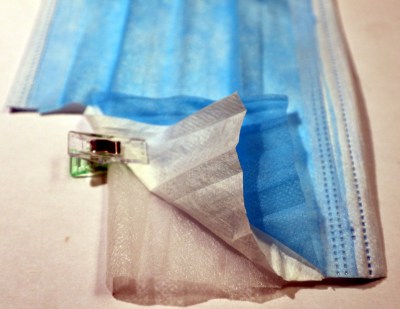

The next mask up for dissection is a Chinese-manufactured three-layer surgical mask with T3210-2016 spec, whose box clearly states that it isn’t a medical device. That warning sounds concerning but in this case it isn’t; masks to that particular standard are intended to be worn by the general public and not by medical staff. In fact this mask is purpose-made as everyday-life dust and droplet-catching PPE, so is just the job. Cutting it open reveals three layers with the middle filter layer being a dense non-woven fabric, and the micrometer reveals it to have a svelte 0.28mm compressed thickness.

The final mask is another dust mask, a Silverline single-layer mask from a pack I bought for showing people round a dusty church tower. It’s a single layer of 0.45mm thick stiff blown-polymer fabric moulded into a mask shape, and its packaging has the ominous warning that it does not offer rated protection to the wearer. It was very cheap indeed and just about adequate for the purpose I bought it for, but I have to admit I’d be happier with more than its very basic level of protection during the pandemic.

All three masks feature a piece of stiff wire or metal strip above the nose designed to fit the contours of the bridge of the nose and clamp shut any gaps through which breath can escape. It’s easy to tell whether they are effective if you wear glasses, because they will immediately steam up if damp air from your breath escapes. Of the three it was the disposable surgical-style mask that did the worst job of this, the FFP3 had a very sturdy plastic and wire tape that lets nothing through and the cheap unrated mask has a metal strip, but the surgical-style mask’s single piece of thin wire simply isn’t up to the job.

I’ve worn all three for extended periods of time to test them, and while driving into town for a prescription wearing this one I had to stop and take it off as the risk of not seeing where I was going became too great. This can be mitigated with folded-up kitchen towel to plug the gaps or even medical tape to secure it, but such things rapidly become very annoying.

As for the fogging, there is some advice out there for this as well. Using dish soap that does not have lotion in it, or say that it’s for sensitive skin will work. Apply to the inside of the lens, let sit a bit, then buff it until clear. The same is said to work with shaving cream although I’ve yet to try either method.

Freedom To Be Uninfected

What’s to be gained from this insight into masks and their construction? In the first instance, it pays to be educated and informed when finding a mask for yourself. Over the past few months I’ve been offered the chance to buy masks from everyone from my PCB supplier through the local tool shop to my stationery provider, alongside any number of unsolicited emails. It’s a confusing marketplace with traps for the unwary that with luck will have become a little clearer.

In the next part of this series I will look at home made mask design and demonstrate how I have made masks of my own. Dust off your sewing machine, that article will be out next week.

No comments:

Post a Comment