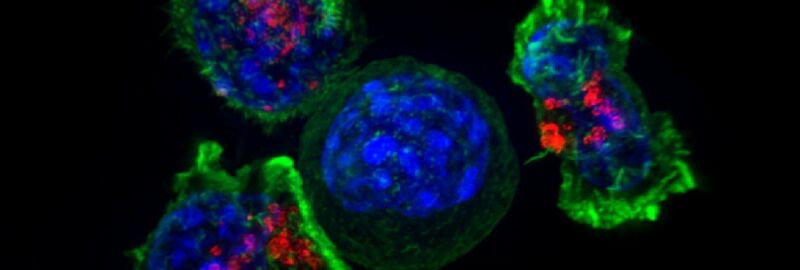

Enlarge / T-cells attacking a cell recognized as foreign. (credit: NIH)

Ultimately, the only way for societies to return to some semblance of normal in the wake of the current pandemic is to reach a state called herd immunity. This is where a large-enough percentage of the population has acquired immunity to SARS-CoV-2—either through infection or a vaccine—that most people exposed to the virus are already immune to it. This will mean that the infection rate will slow and eventually fizzle out, protecting society as a whole.

Given that this is our ultimate goal, we need to understand how the immune system responds to this virus. Most of what we know is based on a combination of what we know about other coronavirus that infect humans and the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. But now, data is coming in on the response of T-cells, and it indicates that their response is more complex: longer-lasting, broadly based, and including an overlap with the response to prior coronavirus infections. What this means for the prospect of long-lasting protection remains unclear.

What we know now

SARS-CoV-2 is one of seven coronaviruses known to infect humans. Some of these, like SARS and MERS, have only made the jump to humans recently. While more lethal than SARS-CoV-2, we are fortunate that they spread among humans less efficiently. These viruses seem to provoke a long-lasting immune response following infections. That's a sharp contrast to the four coronaviruses that circulate widely with humans, causing cold-like symptoms. These viruses induce an immunity that seems to last less than a year.

No comments:

Post a Comment