The 700-horsepower Porsche 911 GT2 RS is already pretty darn fast — over three times faster than the average regular-person car on the road today. For the sports car enthusiast, there’s likely no ceiling on the need for speed and performance. And so, Porsche was able to wrangle another thirty horsepower out of their limited-run supercar by printing a set of ultra-lightweight pistons.

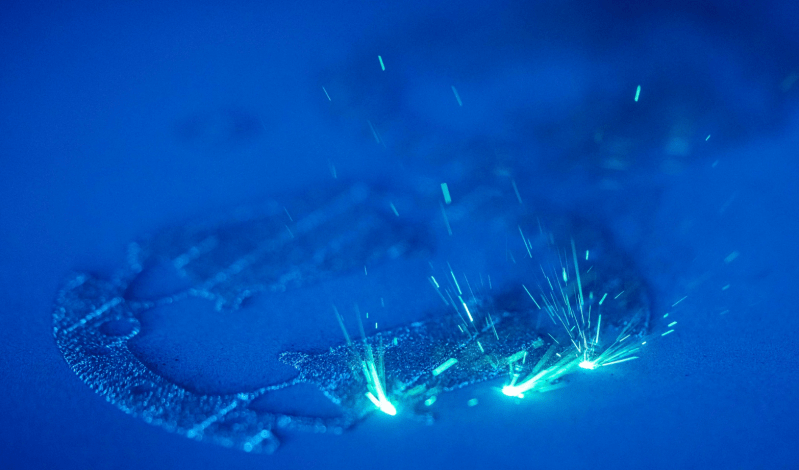

These pistons are printed from high-purity aluminium alloy powder that was developed by German auto parts manufacturer Mahle. Porsche is having these produced by Mahle in partnership with industrial machine maker Trumpf using the laser metal fusion (LMF) process. It’s a lot like selective laser sintering (SLS), but with metal powder instead of plastic.

The machine dusts the print bed with a layer of powder, and then a laser melts the powder according to the CAD file, hardening it into shape. This process repeats one layer at a time, and supports are zapped together wherever necessary. When the print job is finished, the pistons are machined into their shiny final form and thoroughly tested, just like their cast metal cousins have been for decades.

Leaner and Meaner

Generally speaking, prototyping car parts with a printer is much faster than traditional methods. There are no molds to be made, which cuts down on both time and expense. These pistons don’t just have a cool origin story — they have advantages over cast pistons that make them objectively better.

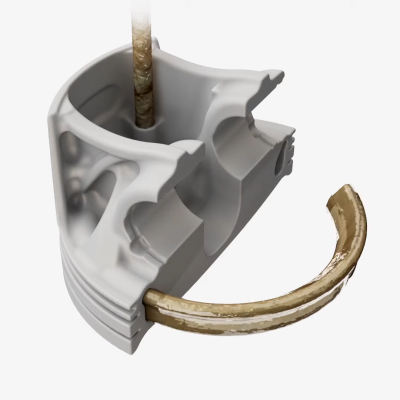

For one thing, additive manufacturing allows for designs that aren’t possible with casting. All of the fat has been trimmed from these pistons — in this design, there is only material where forces will act upon the piston, so it ends up weighing 10% less than regular pistons.

This lean design leaves plenty of room for a built-in cooling system, where oil shoots up through the bottom of the piston head and circulates through the areas that get the hottest. When you have lighter, cooler pistons, the engine can work harder and run faster.

This isn’t Porsche’s first foray into printed parts. Custom bucket seats are an option for two current models, and they also offer certain printed aftermarket replacement parts here and there for models that are no longer in production.

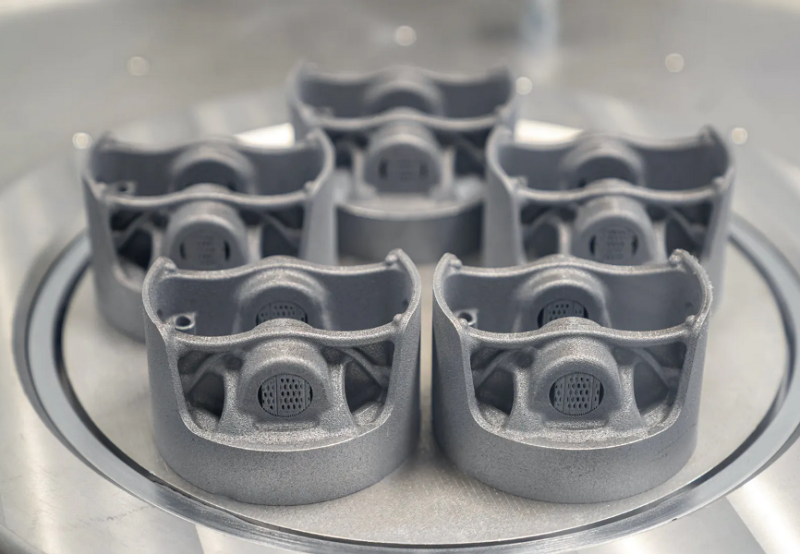

Porsche aren’t using these powerful pistons in production cars just yet. The laser metal fusion process is much better suited for small-scale production, limited run parts, and prototyping, at least for now. Printing a bed of five pistons takes twelve hours, according to this video about the printing process.

High-Stress Print Jobs

What could possibly go wrong with a printed version of something that’s designed to move so quickly under pressure? Probably nothing, though there hasn’t been time for long-term observation. Mahle says the printed pistons are extremely strong, and that they undergo the same rigorous testing as forged pistons. This includes a pulsation test to make sure it won’t crack under stress, and a tear-off test of the area where the piston rod connects. Then they put the pistons through a 200-hour stress exercise on a 911 GT2 RS test engine.

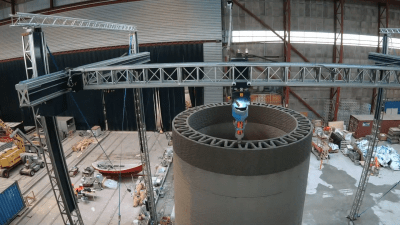

3D printing has been pushing the limits in other industries, too. You’ve no doubt heard of entire houses being printed in a matter of days. Concrete printers are also helping wind turbines to reach new heights by allowing gigantic bases to be printed on-site. The taller a wind turbine is, the better, but the added height necessitates a thicker base. In the US, the base size is limited by, of all things, the height of highway overpasses.

And as far as additive manufacturing for ad hoc replacement parts goes, it doesn’t get much more high-stress than a nuclear reactor. Even so, there’s a project underway at Oak Ridge National Laboratory to create a reactor with as many printed parts as possible. And printing replacement parts for out-of-production reactors is already happening. A few years ago, Siemens switched out a faulty impeller with a printed version, and Westinghouse printed a thimble for holding active fuel rods.

Would you drive a car with printed pistons? You probably won’t be printing those on your own at home anytime soon, but you could already be making replacement badges for your project car, or given enough time, piecing together a full-size plastic Lamborghini.

No comments:

Post a Comment