In the early 1940s, several countries saw an incredible shift in agriculture. What were called “victory gardens” were being planted en masse by people from all walks of life, encouraged by various national governments around the world. Millions of these small home gardens sprang up to help reduce the price of produce during World War 2, allowing anyone with even the tiniest pot of soil to contribute to the war effort.

It’s estimated that in 1943 alone, victory gardens accounted for around one third of all vegetables produced in the United States. Since then, however, the vast majority of these productive gardens have been abandoned in favor of highly manicured, fertilized, irrigated turfgrass (which produces no food yet costs more to maintain), but thanks to the recent global pandemic there has been a resurgence of people who at least are curious about growing their own food again, if not already actively planting gardens. In the modern age, even though a lot of the folk knowledge has been lost since the ’40s, planting a garden of any size is easier than ever especially with the amount of technology available to help.

As someone who not only puts food on the table as a writer for a world-renowned tech website but also literally and figuratively puts food on the table as a small-scale market farmer, there are a few things that I’ve learned that I hope will help if you’re starting your first garden.

You Can Garden Anywhere, But Location Does Matter

For reference, I live in south Florida (zone 10b, which we will talk about later) and I sell various salad greens to farmers markets near me. I also grow lots of other edible, but unprofitable, plants for fun as well. The soil here is mostly worthless sand, but that touches on the two most important things to know before getting started: your own climate and soil type.

Garden Keystone: Climate. The most important of these is climate, since almost every other factor for a healthy garden depends on it, so the first step is to figure out what climate your plants will grow in.

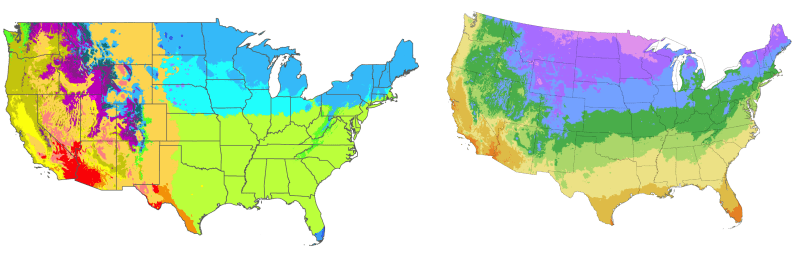

The Köppen climate classification system can help here, as it is much easier to grow plants that are native to the climate they will be growing in. For example, it would be difficult (although not impossible) to grow a mango tree in Michigan, or an apple tree in Texas, or a date palm outside of a desert. Another resource that is helpful for determining if your plants of choice will grow where you live is the USDA plant hardiness zone map. (Other countries have similar resources available.) This is a map of the lowest expected temperature in a typical year for any given location. A plant that is “hardy” to zone 6, for example, will survive temperatures down to -23 C but a plant that is only hardy to zone 10b (as I mentioned before) will likely not survive if the temperature even approaches freezing. It is important to note that this scale doesn’t apply in reverse, i.e. a plant hardy to zone six may or may not survive in a higher numbered zone.

Related to climate, you will also need to make sure your plants are growing in their correct season. For example, tomatoes are a common vegetable to grow in the summer in temperate climates, but if you live in a place that is hotter than average (like I do in south Florida) you may find out that almost all tomatoes (with some exceptions) will die in the extreme heat. To solve that problem, most people near me plant their tomatoes in October and harvest all the way through the following April, but if you happened to be living in Vermont you’d need to make some obvious adjustments to this schedule.

Garden Keystone: Soil Types. The next thing to consider is soil type. Virtually all soils have some sort of plant that loves to grow in them, and it’s usually not too difficult to amend soil for small plots to allow other things to grow in them. For example, sweet potatoes love sandy soil with low nutrient content, but planting a banana tree next to them will not be fruitful. All states in the US have an agricultural university with extension offices that soil samples can be sent to, and these labs can tell you how much of various nutrients are available in the soil and some suggestions on what to plant, or how to add various supplements to the soil. They can also make recommendations for what plants you can grow natively, and are a tremendous resource. Soil is the most important thing to watch when growing any plants, though, and if you take care of your soil properly a lot of other aspects of your garden will fall into place naturally, such as disease resistance, pest resistance, and improved yields.

From Kitchen Window to Tilling the Yard Under

Once climate and soil type have been figured out, though, there is essentially no end to the number of gardening rabbit holes (pun intended) that can be fallen into. Did your worthless Bradford pear tree fall over in a storm? Plant an apple or peach tree! Want a maintenance-free groundcover for a patch of lawn that won’t ever grow because it’s too hot or sunny? Might be time to plant some sweet potatoes. Some of the more extreme of us have plowed up our entire yards to grow food, but it’s best to at least start small.

Even if you have limited space or no access to any land as an apartment dweller, for example, there’s still some ways that you can grow some food for yourself. With a few pots of topsoil from the local gardening center, or by being patient and using kitchen scraps to make your own compost, it’s possible to grow a lot of herbs and spices near open windows, especially green onions, basil, oregano, and many others. With a small grow light, other things like lettuce and peppers are possible as well.

Technology can really step up in this area. If you have a fish tank, for example, it’s possible to filter the water for the fish using plants that will benefit from the waste the fish generate. This symbiotic relationship is known as aquaponics, and setups can be as small as a few plants, a grow light, and an aquarium with only a few fish. Of course, aquaponics projects can be huge as well, but if you have limited space and already have an aquarium then it’s a great starting point. If you don’t have an aquarium, you can build a similar system without the fish known as hydroponics, which we have seen in several projects before.

Apartment Gardening: Fungus

Other things can be grown inside a small space or apartment as well, and some of them aren’t even plants. Various mushrooms can be cultivated fairly easily in buckets of straw or spent coffee grounds. These methods require almost no specialized equipment either. Growing mushrooms also eliminates one of the greatest obstacles to growing plants in an apartment: access to sunlight. Mushrooms don’t require sunlight for the energy needed to grow, so this is a viable alternative to growing plants. While oyster mushrooms are the most popular for starting cultivators, other edible mushrooms can be cultivated indoors as well, such as shiitake, maitake, and lion’s mane mushrooms.

Making Small Plots Yield More Produce

If you do have a good amount of land and are ready to get started using technology to help cultivate as much food as possible for your area, climate, and soil type though, there is perhaps no better resource than Akiba’s various projects. He is a member of Freaklabs and while his projects aren’t all devoted to farming, and from his home base at Hacker Farm outside of Tokyo, a good percentage of his projects are aimed at helping farmers to improve yields or otherwise making their jobs easier. From sensor nets for improving rice farming to entire farms devoted to using and teaching technology, his work offers more than enough inspiration for the budding gardener or farmer to draw from. I have used some of his projects for inspiration on my own small farm, especially when it comes to managing irrigation with a limited/expensive water supply, so there is certainly a wealth of knowledge there to draw upon. Others that have had popular farming-oriented builds here include Brad aka [AtomicZombie] who grows a good chunk of his own food in the Canadian prairies and has built some unique tools to help manage his homestead as well.

Eating Something You Grew is So Much More Satisfying, and Often Objectively Better Tasting

The process of growing at least some of your own food is possible in virtually every circumstance, provided that you understand the basics of climate and soil type and have reasonable expectations. As a beekeeper (a rewarding hobby in itself that can greatly improve your garden’s yield, as well as provide tasty honey, useful wax, and even tasty adult beverages), there’s a common saying that easily translates to growing a garden: “All beekeeping is local”. This means that only you can find out what works best for your specific set of circumstances.

In a sense, all gardening and farming is local too, and a certain amount of trial and error will occur before you really get the hang of your current situation despite all the things you have read online about the “right” ways to grow various plants. But using the technology widely available to most of us as part of the Hackaday community should make the process of starting a modern victory garden much easier. You’ll end up eating more produce as you don’t want your hard work to go to waste. And I’ll put my garden tomatoes up against those in a grocery store any day of the south-Florida winter.

No comments:

Post a Comment