In the matter of technological advancement, we are as a species, mostly insatiable. The latest toy, the fastest silicon, the largest storage, the list goes on. Take digital cameras as an example, what was your first one? Mine was a Casio QV200 in about 1997, I still have it somewhere though I can’t immediately lay my hands on it, and it could hold a what was for its time a whopping 64 VGA-resolution pictures in its 4Mb of onboard memory.

It’s a shock to realise that nearly a quarter century has passed since then, and its fixed-focus 640×480 camera module with a UV-sensitive CMOS sensor that gave everything a slight blue tint would not even grace the cheapest of feature phones in 2020. Every aspect of a digital camera has improved beyond measure since the first models in the 1980s and early 1990s that started to resemble what we’d know today as a standalone digital camera, they have near-limitless storage, excellent lenses, huge and faithfully-reproducing sensors, and broadcast-quality video capability.

But how playful have camera manufacturers been with the form factor? We see reporters in sci-fi movies toting cameras that look nothing like their film-based ancestors. What do our real-life digital cameras have on offer as far as creative body design goes?

When Photographic Companies Didn’t Drive The Digital Camera Market

Every aspect of a digital camera has improved, that is, except one. When mass-market digital cameras came out, their designers experimented with the form factor of a camera. The Casio was an example, instead of being a brick with a lens sticking out of its middle it put the camera in a rotating turret on one of its ends. For the first time it was possible to take a picture from an angle other than with your face up to the viewfinder.

Other manufacturers took similar departures from the norm, just to note a few examples Apple’s 1994 QuickTake 100 had a form factor about the size of a paperback book with lens and viewfinder at opposite ends, Nikon’s 1996 Coolpix 100 had a vertical form factor that concealed a PCMCIA card for retrieving photos, and a series of Ricoh cameras through the ’90s had a candy-bar format reminiscent of 110 cartridge film cameras but with a flip-up LCD on top.

Product designers were given free reign to reinvent the camera after it had remained essentially unchanged for decades since the widespread adoption of 35mm film, and the result was an explosion of interesting new devices. Some of them were maybe a little avant garde, but among them were a few that genuinely did make the job of taking a photograph that little bit easier.

By the 2000s this era of creativity stuttered to a halt, and digital cameras retreated to being updated facsimiles of their 35mm ancestors, but with LCD screens. Compact cameras lost their viewfinders and were a bit slimmer than their film ancestors, an entirely new genre of not-quite-an-SLR bridge camera appeared that yet again looked as though it might have a 35mm canister somewhere, and DSLRs were replicas of their film predecessors, but bulging and overweight as if on steroids and festooned with buttons. Now compact cameras are all but dead in the face of mobile phones, and bridge cameras have given way to mirrorless cameras that look for all the world like a 35mm rangefinder. Dare I say it, cameras are a little bit boring.

Your Parents Didn’t Want Anything Exciting

So, what went wrong? The answer lies with who was making cameras in the 1990s, and who was buying them. On the whole your parents didn’t have a digital camera, instead they were the preserve of the early adopter. Probably quite a few of you who went on to become Hackaday readers, in fact. And the other side of the coin was that they were being manufactured by electronics companies rather than the photographic brands from whom we might have traditionally bought a camera. Companies who brought the product design experience of making computer peripherals to the table rather than the entrenched idea of how a camera should look.

Customers like us wanted something visibly high-tech and manufacturers were ready to break the mould. It was the perfect recipe for some exciting products. By comparison in the 2000s, your parents bought their first digital camera, and they probably did it from a brand they trusted because they already owned a film camera with the same logo. Their innate conservatism brought to the fore the replicas of 35mm form factors as something safe, and as a result here we are in 2020 when my camera looks like one made in the 1950s.

All is not lost however. Digital cameras replaced flat, rectangular images made from film with flat, rectangular images made from a digital sensor. But a new generation of cameras is exploring past that paradigm. Here you can see the form factor for a 360 degree camera that stitches together the captured image from two different hemispheric lenses. And all signs point to 3D cameras peeking over the horizon. Surely these form factors will be used to echo how much their features stand apart from what came before, following in the footsteps of action cameras that set them selves apart by flaunting their robust, almost indestructible nature.

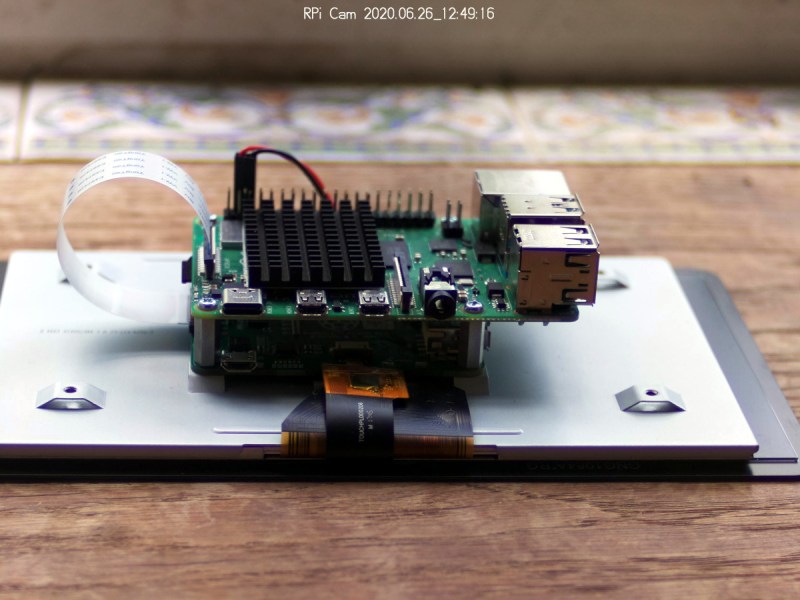

And for those with a personal interest in pushing the boundaries of camera form factors, it’s a great time to be a hardware hacker. Affordable components are available to enable the construction of almost anything. Given a camera module and a small computer we can step in and produce the camera we want, rather than the one our parents want. I put this to the test, picking up a Raspberry Pi HQ camera module, and a C-mount lens. It may not be the match of a truly high-end model, but it’s a decent enough combination that opens up limitless possibilities for the experimenter.

The Future Of Camera Form Factors In Your Hands

In a way the form factor I arrived at is a bit conservative, being a pistol grip design with a nod towards 8mm cine cameras and more recently the FLIR thermal cameras. But it’s an illustrative piece to demonstrate the ease of creating a usable camera with these components.

Some work in OpenSCAD produced a simple triangular chassis with a front mounting for the camera module and a sloping face to which a Raspberry Pi case with display can be attached using Velcro strips. There are tapered locating points for a handle on both sides and the bottom to which handles or other mountings can be attached. The pistol grip is probably oversized as it’s designed to hold two 18650 cells in holders, but it could easily be replaced by a side grip, a GoPro-style accessory clip, or anything else that the imagination could come up with. Find all the files in my GitHub repository. On the software side, given time I could surely come up with a beautiful interface, but for now I’m running [silvanmelchior]’s web interface which I can load in a very slow web browser on an original single-core Pi model B+. In time I’ll look at ways to achieve a working preview without the Raspbian X bloat (If anyone can help me get the framebuffer version of Netsurf to compile and run instead of falling over on a Model B+, I’d be much obliged!), but for now the hardware has been the driving force.

In use, it’s an unexpected return to a bygone era of completely manual cameras. Even my old 1980s 35mm SLR had automatic light metering and a prismatic focusing aid, by contrast this is photography entirely by the seat of one’s pants for someone used to an autofocusing mirrorless camera. But a little more work on the aperture and focus is soon a part of the flow, and I can take decent quality photographs with it. The final result is definitely on the functional side, but I like to think I’ve avoided producing the Homer of cameras.

The days of delightfully wacky digital camera form factors may now be far behind us then, but I hope I’ve shown that even if the camera manufacturers no longer have the courage to break any moulds then the hacker community can still have fun in this arena. We’ve finally reached the point of having affordable high-quality camera components at our disposal, so it’s time to get creative. How are you going to re-interpret the camera, please share it with us!

No comments:

Post a Comment