Since the last Concorde rolled to a stop in 2003, supersonic flight has been limited almost exclusively to military aircraft. Many have argued that it’s an example of our civilization seeming to slip backwards on the technological scale, akin to returning to the Age of Sail. There’s no debating that we have the capability of moving civilian passengers and cargo at speeds above Mach 1 safely, it’s just something that isn’t done anymore.

Of course to be fair, there’s plenty of good reasons why the sky isn’t filled with supersonic aircraft. For one, they’ve historically been more drastically expensive to build and operate than their slower peers. The engineering that goes into an aircraft that can operate for an extended period of time at supersonic speeds doesn’t come cheap, nor do the materials required. But naturally, the same could have been said for commercial jet aircraft at one time. With further development, the cost would eventually come down.

The real problem holding supersonic aircraft back is much more practical: they are just too loud. From the roar of their powerful engines on takeoff to the startling and sometimes even dangerous “sonic boom” they leave in their wake, nobody wants them flying over their homes or communities. In fact, civilian flight above Mach 1 over land has been outlawed in the United States for exactly this reason since 1973 under the Federal Aviation Administration’s regulation 91.817.

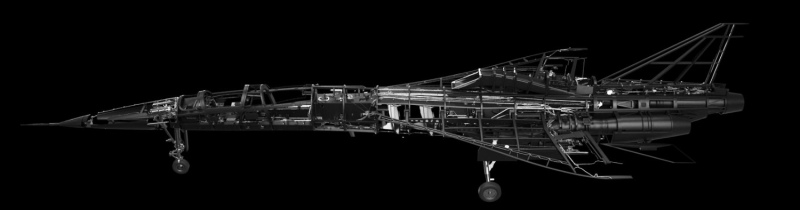

For any commercial supersonic aircraft to be viable, it needs to not only be much cheaper to build and operate than older designs, but it also needs to be far quieter. Which is exactly what Boom hopes to demonstrate with their XB-1 prototype. The sleek craft will never enter into commercial service itself, but if all goes according to plan during its 2021 test flights, it may prove that the state-of-the-art in aircraft design is ready to usher in a new era of supersonic civilian transport.

On The Shoulders of Giants

When the Concorde was being designed in the early 1960s, commercial jet aircraft were still a relatively new concept. It represented a technological quantum leap, and had more in common with military research aircraft than anything that had ever carried a paying passenger. Many core components, such as the Olympus 593 engines, had to be tailor made for the Concorde. This made it an exceptionally expensive aircraft to develop and manufacture, and while estimates vary considerably, in the end the program is believed to have cost nearly 10 billion dollars.

When the Concorde was being designed in the early 1960s, commercial jet aircraft were still a relatively new concept. It represented a technological quantum leap, and had more in common with military research aircraft than anything that had ever carried a paying passenger. Many core components, such as the Olympus 593 engines, had to be tailor made for the Concorde. This made it an exceptionally expensive aircraft to develop and manufacture, and while estimates vary considerably, in the end the program is believed to have cost nearly 10 billion dollars.

But that’s not the case for the XB-1. Many of the core technologies that Boom has identified as critical to the success of commercial supersonic aircraft, such as a carbon fiber airframe, are already well understood. Like essentially all modern aircraft, the design of the XB-1 has also benefited tremendously from the advancements in computational fluid dynamics. Physical testing which could have taken years previously can now be simulated on the computer in a fraction of the time.

Another huge benefit is the use of an existing engine, the General Electric J85. Originally designed for the United States Air Force in the 1950s, it’s certainly not a new engine. But it’s gone through several revisions to increase its performance and efficiency, and its expected to remain in service for at least the next few decades.

A Familiar Face

It’s no coincidence that the XB-1 bears more than a passing resemblance to NASA’s X-59 Quiet Supersonic Technology (QueSST) aircraft. While Boom has been relatively cagey about how quiet their planes will eventually end up being, it’s clear from even a cursory glance that they’ve adopted some of the design elements that NASA and X-59 prime contractor Lockheed Martin believe will help mitigate the sonic booms generated by their experimental aircraft.

Both planes utilize a long and thin fuselage to prevent the front and rear pressure waves from compressing together and generating an energetic shock wave. Instead of hearing the loud crack of these waves slamming into each other, an observer on the ground would hear a series of dull thumps. While this doesn’t solve the problem completely, it should reduce the traditional sonic boom to the point it would simply blend into the normal background noise of life in an urban environment.

That said, the XB-1 clearly isn’t taking the concept quite as far as the X-59. Boom is ultimately looking to create a practical commercial aircraft, whereas NASA is researching the limits of the technology. The almost comically long nose extension on the X-59 will surely provide NASA with a wealth of data about sonic boom abatement, but probably won’t become a standard feature on aircraft of the future.

Open For Business

Boom says construction of the XB-1 will be largely completed by the end of the year, and that flight tests will start in 2021. That just so happens to be when NASA and Lockheed Martin plan on starting flight testing of the X-59. Assuming neither project is significantly delayed by the global COVID-19 pandemic, of course.

Boom says construction of the XB-1 will be largely completed by the end of the year, and that flight tests will start in 2021. That just so happens to be when NASA and Lockheed Martin plan on starting flight testing of the X-59. Assuming neither project is significantly delayed by the global COVID-19 pandemic, of course.

But for Boom, the successful testing of the XB-1 is just the beginning. After validating their core technology and design principles on the smaller craft, the company says they will immediately begin construction on a Mach 2.2 capable airliner they call Overture.

The 52 meter (170 ft) long aircraft would be able to carry up to 55 passengers, and is intended for high-speed international business flights. Even though it’s projected to be considerably quieter than the similarly sized Concorde, Boom envisions the Overture primarily flying transoceanic routes where noise won’t be a concern. While the timetable obviously depends on how well the XB-1 performs, Boom hopes to have the Overture ready to enter service by 2027.

No comments:

Post a Comment