When you’re a kid, one of the surest signs of summer is hearing the happy sound of the ice cream truck crawling through the neighborhood. You don’t worry about how that magical truck is keeping the ice cream cold, only that it rolls down your street, and that the stars align and your parents give you money for a giant ice cream-cookie sandwich with the edge rolled in tiny chocolate chips.

In the early days of mobile refrigeration, ice cream trucks and other food delivery vehicles relied first on ice, and then dry ice to keep perishables cold. Someone eventually invented an electric cooling system, but those had to be recharged periodically at power stations. There was also a short-lived mechanical system, but it was highly susceptible to road vibrations.

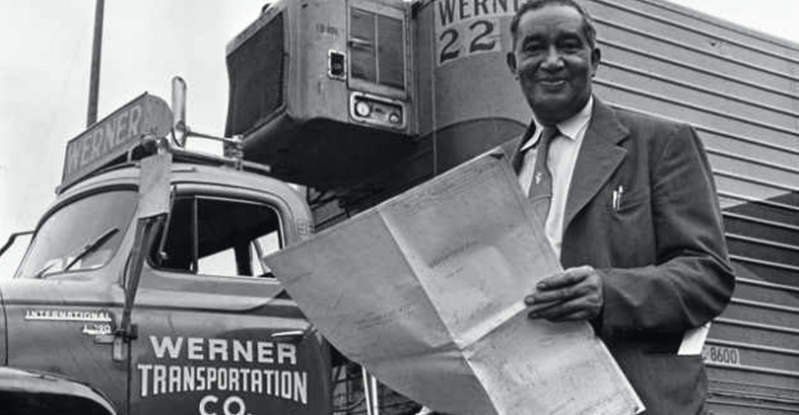

Until Frederick McKinley Jones came along, mobile refrigeration was fledgling, and sources of perishable food were extremely localized and limited. In the early 1940s, Frederick patented the first practical automated refrigeration system for trucks, and it revolutionized the shipping and storage of food and medicine.

A Cold Childhood

Frederick McKinley Jones had what most would consider a rough start to life. He was born in 1893 to a Black mother and an Irish father in Cincinnati, OH. Frederick’s mother abandoned him when he was a baby, and his father struggled to raise him alone.

When no orphanage would accept the seven-year-old Frederick, his father sent him to live with a Catholic priest across the river in Kentucky. Two years later, his father died.

Little Fred was a tinkerer from the start, and loved to play around with his father’s pocket watch. The priest encouraged Fred’s interest in mechanics, and let him fix the congregation members’ cars while they sat through the church services.

Fred lived with the priest until he was eleven, when he quit school and ran away, back across the river to Cincinnati. He found work as a janitor in a garage, and by the age of fourteen had worked his way up to mechanic and started building race cars for his boss. Within a year or two, the boss fired him for racing cars when he was on the clock.

Handyman Fred

After that, Fred moved around a bit and took odd jobs to support himself. One night he offered to fix the boiler at a hotel in exchange for a room and a few meals, though he had no experience with boilers or the required tools. Fred did such a good job that the hotel owner offered him a job as a mechanic on his family’s large farm in Hallock, Minnesota. Fred packed his bags and moved once again.

The farm proved to be a great opportunity for Fred. An engineer working there helped him study and eventually earn his engineering license. Soon after, Fred was called up to fight in WWI. Once the officers saw what he was capable of, Fred’s mechanical skills were soon in great demand, and he was asked to work on all kinds of equipment and vehicles. Within a short time, Fred was promoted to sergeant.

When the war was over, Fred went back to the farm in Hallock. He taught himself new skills like electronics in his spare time by reading library books and taking mail order courses. Fred quickly became known around the town as a handyman and problem solver, and built many things for the town over the years, including a transmitter for the town’s first radio station.

After one of town doctors complained about having to wheel patients down to the x-ray equipment all the time, Fred built a portable x-ray machine. He also built what is arguably the first snowmobile by slapping skis to an airplane fuselage and adding a propeller on the back. The purpose? Helping doctors get around in the snow to make house calls.

When talkie pictures came along and Hallock’s only theater couldn’t afford to upgrade their equipment, Fred built a machine that could synchronize film and sound. This invention caught the attention of a film industry businessman from Minneapolis named Joseph Numero, who hired him in 1930.

The King of Cool

But the problem that would define Fred’s legacy came about as an offhand comment. One of Numero’s golf buddies complained to him about a poultry truck that got stuck overnight. All the ice melted, and the entire shipment was ruined. Numero was only recounting the story to Fred, but he took the problem seriously anyway.

The problem was twofold; vehicles lacked the power necessary to run a refrigeration system, and the vibrations present in automotive applications made existing refrigeration unfeasible.

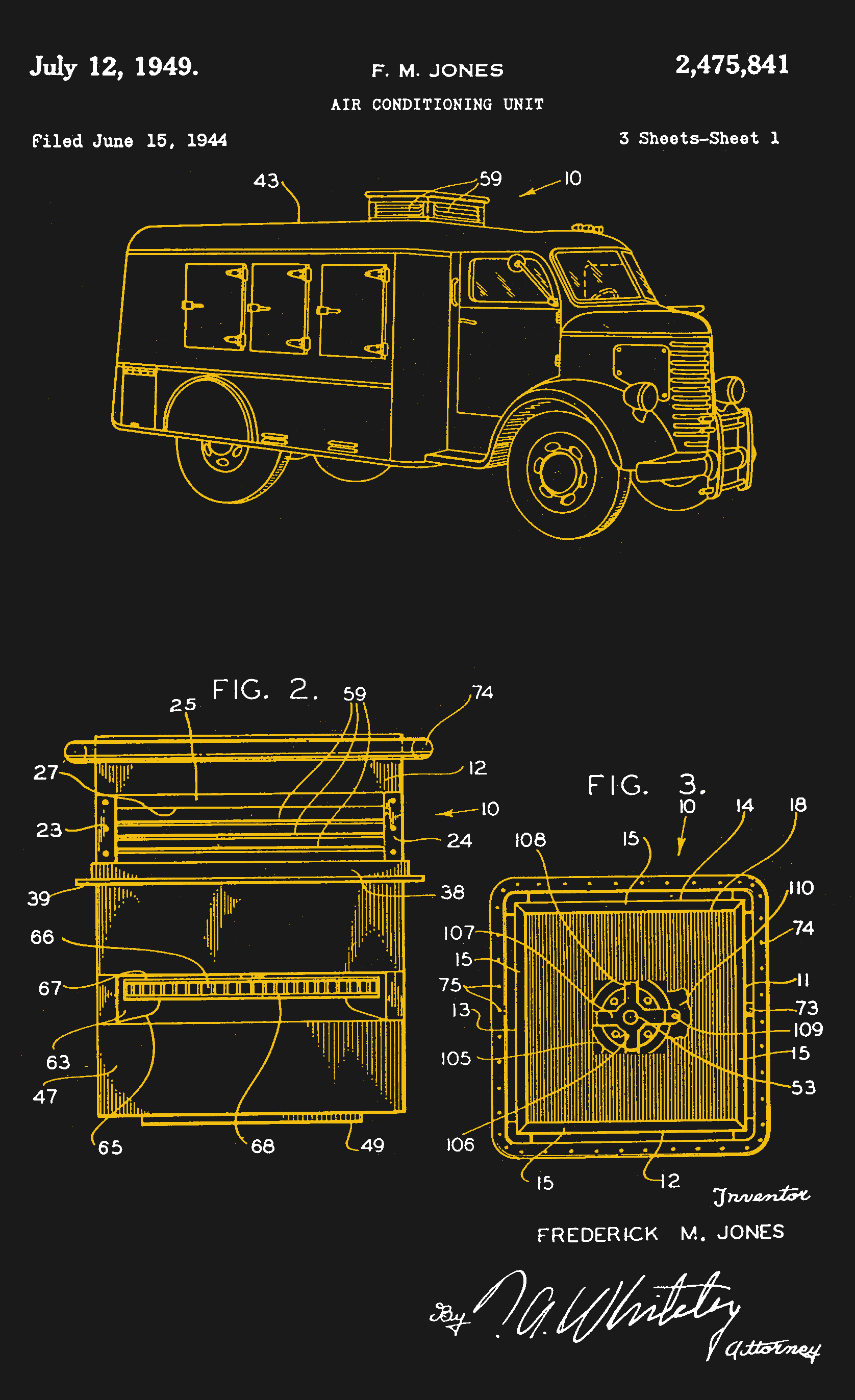

Fred’s approach was to invent a single unit for installation in the roof of any enclosure, made up of the cooling unit and the motor to drive it. This made it both compact and simple to repair. The use of a dedicated engine solved the power issue, and by using a thermostatically controlled motor (for which he was issued a patent) the refrigeration unit was automatic. With Fred’s solution in hand, Numero quit the film industry so that the two could go into the refrigeration business together. They started the US Thermo Control Company, later called Thermo King.

Fred’s invention arrived in time to be of great service in WWII. The US Department of Defense chose one of Fred’s mobile refrigeration units for use throughout the armed forces, and they cropped up everywhere from B-29 cockpits to field hospitals. The idea was soon expanded to planes and boxcars, and the cold transport chain that we all greatly benefit from today was born.

Illness forced Fred to retire from Thermo King in the late 1950s, and he died of lung cancer in 1961. He was the first African-American to receive the National Medal of Technology, which he was posthumously awarded in 1991.

Frederick Jones hasn’t gotten all the credit he deserved throughout the years for a couple of reasons. He failed to apply for patents on his earlier inventions. But also, he was a half Black man inventing things in the early American 20th century. Everywhere he went, people doubted his abilities, but they usually thawed out once they saw what he was capable of. Fred was a self-made man, and it’s clear that he always took his own advice: be willing to work, be willing to read and study to enrich your life, and always believe in yourself.

No comments:

Post a Comment