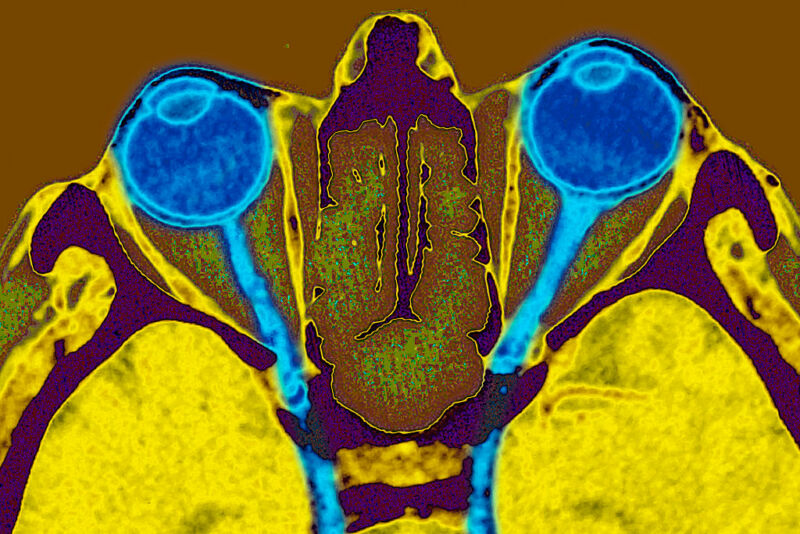

Enlarge / Two eyes and their optic nerves, seen on a radial section scan. (credit: BSIP/Getty Images)

Our visual system is complex, with photoreceptors that pick up incoming light and at least three types of neurons between those and the brain. Once in the brain, visual input is interpreted by multiple dedicated regions that build a scene out of small pieces of shape and motion. The outcome of that processing may be further interpreted by areas of the brain that handle things like reading or face recognition.

With all that complexity, lots of different things can go wrong. Accordingly, we'll likely need multiple solutions if we want to try to correct these problems. So, it was nice to see the results of two very different approaches to tackling visual problems tested in experimental animals this week. One group manipulated biology to correct problems in the transmission of information between the eye and the brain, while another group used electronics to bypass the need for an eye entirely.

Refreshing nerves

One of the most exciting developments in tissue repair has been the recognition that we could convert many cell types into stem cells just by activating four specific genes. Unfortunately, activating those genes widely in mice kills them, as the genes also promote loss of normal cellular identity and uncontrolled division. A huge, US-based collaboration suspected many of these problems were due to one of those four genes (called MYC), and so it focused on working with the remaining three. The first showed that activating these three in cells from older mice restored properties that were typical of younger cells without any loss of normal cell function.

No comments:

Post a Comment