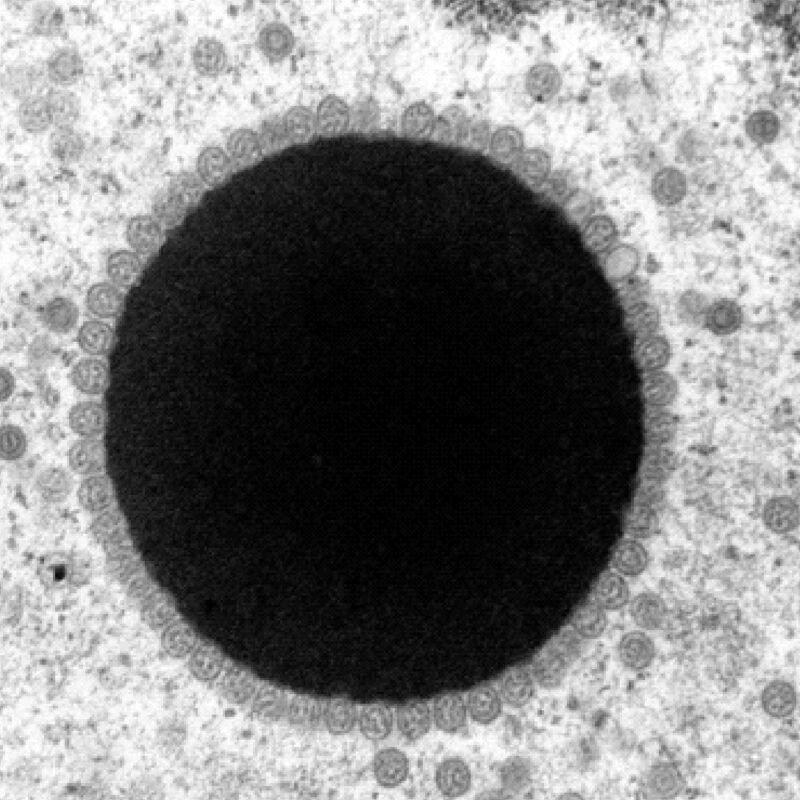

Enlarge / Herpes viruses getting ready to infect new cells. (credit: Thierry Work, USGS)

One of the defining features of viruses is that they rely on host proteins in order to reproduce. A host cell will often copy viral genes into RNAs and then translate those RNAs into proteins, for example. Typically, a mature virus that's ready to spread to another cell has little more than viral proteins, the virus's genetic material, and maybe some of the host's membrane. It doesn't need much else; all the proteins it needs to reproduce further should be present in the next cell it infects.

But some data released this week may have found an exception to this pattern. Members of the herpesvirus family appear to latch on to a protein in the first cell they infect and then carry this protein along with them to the next cell. This behavior might be helpful because of the normal targets of herpesviruses—neurons, which have a very unusual cell structure.

A long way to the nucleus

Like other viruses, herpesviruses start off by infecting cells that are exposed to the environment. But from there, they move on to nerve cells, where they take up residency, persisting even when there's no overt indications of infection. These infected cells then serve as a launching point for re-establishing active infections, causing lifetime problems for anyone unfortunate enough to have been infected.

No comments:

Post a Comment